The year was 1849, and the question was being asked in the Illinois State Journal on behalf of a group of Portuguese refugees from the Island of Madeira seeking passage to America to escape religious discrimination. Within the next two years, hundreds of these Portuguese migrants would find their way to central Illinois. And when they arrived, with little more than the shirts on their backs, the citizens of Springfield welcomed them and provided the tools necessary to begin a new life in the United States.

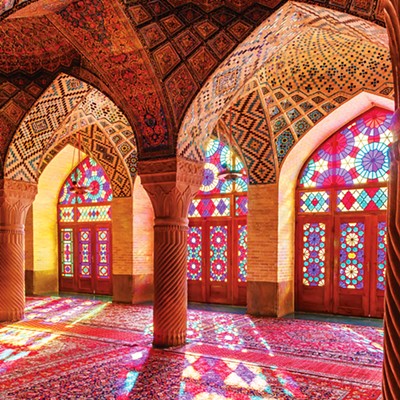

The exiles’ story began in 1838, when a Scottish physician and Presbyterian minister named Robert Kalley traveled to Madeira for his health. Finding that the climate agreed with him, he made the island his permanent residence and soon began encouraging people to join the Presbyterian church.

That nearly 1,000 people did become Protestant at his behest was problematic to many Roman Catholics, who were in the vast majority on the island. When Kalley refused to discontinue his missionary activities, he was imprisoned for five months and his schools were broken up. In the meantime, the congregants of his small Presbyterian church were subject to persecution in the form of taunts, threats and incarceration.

That ship had been sent by the planters of British West India, who were eager to take in the refugees. The British slave trade had been abolished in 1833, and now the plantations on the British colonies in the Caribbean were sorely in need of labor. In all, more than 2,000 Portuguese refugees removed to Trinidad, Antigua, Demarara and St. Kitts.

Living conditions in the British West Indies were terrible for the refugee laborers. The climate was hot and unhealthy; the work, when it could be found, was grueling and low-paying; the prospect for their children’s futures was bleak. In October 1848, Portuguese Pastor Arsenio Da Silva wrote: “With difficulty do the people at all find labor so as to be able to support themselves and their families... In circumstances of extreme necessity, those of them who sicken, die as much in consequence of want as of the severity of their disease. Their little children are almost naked, and have only rags to sleep on.”

News of the Portuguese refugees’ plight spread throughout the world. Americans were particularly sympathetic to the Protestant exiles, whom they likened to their own Pilgrim forefathers.

On Sept. 15, 1849, a representative of the American and Foreign Christian Union wrote to Erastus Wright of Springfield asking if that city might be willing to take in any of the exiles. The editor of the Illinois State Journal published this correspondence and urged residents of Springfield to agree, noting the need for labor in the city and on surrounding farms. “Besides,” he added, “in assisting these people we should perform a praise-worthy act, as pleasant to those who confer, as it would be grateful to those who receive benefit.”

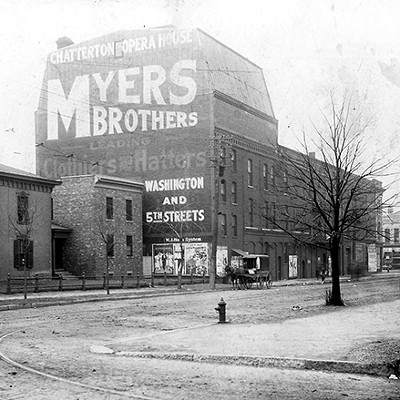

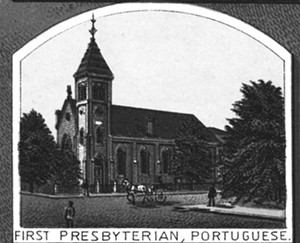

The citizens of Springfield rose to the occasion. On Nov. 13, 1849, 150 Portuguese refugees were welcomed into the city with gifts of cash, food, clothing, bedding and furniture. Most of them settled as a group on the north side of town, along Miller and Carpenter streets between Ninth and Tenth, in an area that became known as “Madeira.”

In the next few years, hundreds more exiles would follow. By 1853 an estimated 1,000 Portuguese refugees had settled in Springfield, Waverly and Jacksonville.

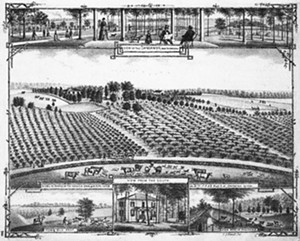

Thirty years after their arrival, the Illinois State Register reflected on Springfield’s Portuguese community, saying, “As a rule they came here poor in purse but rich in determination. They all managed as soon as possible to acquire a piece of ground, no matter how small, which they can call their own, and they cultivate this with all the care and diligence they formerly bestowed upon the little patches of earth between the rocks and hills of their rugged native isle. As a class they are industrious, frugal, upright, peaceful, law-abiding citizens.”

Erika Holst is a writer and museum curator in Springfield.