With children the annual return of that mysterious personage called “Santa Claus,” with his budget of gim cracks and appropriate presents, is full of excitement and is looked forward to with absorbing interest. Illinois State Journal, Dec. 25, 1856

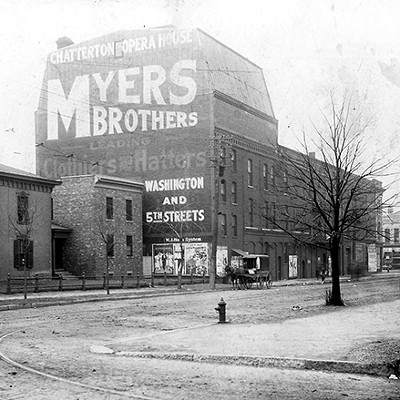

In the 1850s, the arrival of December meant that stores in downtown Springfield would be filled with toys and gifts, and newspapers would be filled with ads reminding holiday shoppers that “Christmas is Coming.” Indulgent father that he was, Abraham Lincoln no doubt purchased goodies for his young sons, Robert, Willie and Tad, well aware that they were counting on Santa Claus to visit their house and fill their little stockings with treats and gifts.

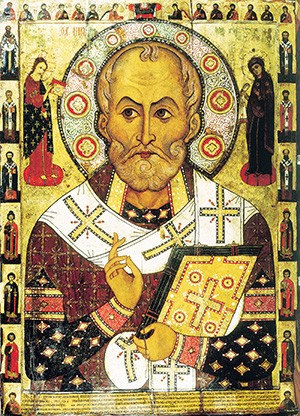

This was not the case in Lincoln’s own childhood, when Santa Claus was not yet, as they say, “a thing.” As a boy, Lincoln likely hadn’t even heard of St. Nicholas. During the course of just one generation at the beginning of the 19th century, St. Nick evolved from an obscure Dutch saint to the beloved American symbol for commercially tinged Christmas cheer.

The original Nicholas was the third-century bishop of Myrna, a small town in what is now Turkey. By about 1200 AD, he was associated with many miracles; one in particular earned him the reputation as the patron saint of children. According to legend, Nicholas visited an inn where the keeper had recently murdered and dismembered three boys and pickled their bodies in barrels. Sensing something wrong, Nicholas discovered the crime and resurrected the victims.

Throughout early modern Europe, St. Nicholas Day (Dec. 6) was a day when the good saint brought gifts to good little boys and girls. This practice fell out of favor in many countries after the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, but the Dutch clung fast to the tradition of St. Nicholas, whom they called Sinter Klaas. When Dutch colonists settled in New York, they brought their tradition with them.

Dutch-American St. Nicholas got a big boost in popularity with the publication of Washington Irving’s satirical Knickerbocker’s History of New York in 1809, which described St. Nicholas flying over housetops in a wagon and dropping presents down the chimneys of good little children.

In 1821, The Children’s Friend became the first book published in America to include lithographic illustrations. This book included a poem about St. Nicholas that embellished Irving’s version: Irving’s flying wagon became a flying sleigh pulled by reindeer, and St. Nicholas arrived on Christmas Eve, not St. Nicholas Day. With the publication of Clement C. Moore’s wildly popular poem, “A Visit From St. Nicholas” (also known as “’Twas the Night Before Christmas”), in 1823, the idea of Santa Claus really took off in American popular culture.

Enter the growing American middle class, who idealized the home, children and pious devotion to God. This influential cultural group seized on the Christmas holiday and domesticated it into an event centered around traditions of family gatherings, religious worship and giving gifts to children.

Santa Claus was an ideal mascot for this new version of Christmas. The American middle class had disposable income to spend, and they were living at a time when the Industrial Revolution fostered the availability of mass-produced consumer goods and improving transportation networks made those goods readily accessible. Moreover, it was a time when children were idealized and childhood was celebrated. Santa Claus gave parents the perfect excuse to spend money on their little angels – though in true moralistic 19th century fashion, children had to behave well and “be good” if they were to receive gifts.

Just what their mythical benefactor looked like was largely up to their imagination, for an image of Santa had not yet been codified in the popular culture. In 1858, for example, Harper’s Weekly depicted Santa as a beardless man with dark hair driving a sleigh pulled by a turkey. Illustrator Thomas Nast is credited with standardizing the image of Santa Claus as a plump, jolly, white-bearded elf in illustrations he did for Harper’s Weekly between 1863 and 1886.

By the mid-19th century, Santa Claus was the undisputed anchor of the Christmas holiday. Springfield fathers like John T. Stuart, who had grown up without St. Nicholas, would find themselves braving snowstorms on Christmas Eve to buy toys so the next morning they could have the satisfaction of seeing that their children’s “eyes glistened when they saw their little stockings all hung in an row and full of toys and candies.”

Erika Holst is Curator of Collections at the Springfield Art Association. She delights in playing Santa Claus to her own little angel, Anders.