The neighborhood looks a lot like any other freshly-minted subdivision across town or across the Midwest -- shiny new houses with attached garages, fenced backyards, preternaturally green lawns and a pleasant uniformity of design, plopped down on a patch of prairie where no houses stood before. It's the kind of place where Beaver Cleaver might have grown up if his parents thought a double vanity in the master bath was more important than old growth shade trees. Oh, and if Ward and June were black.

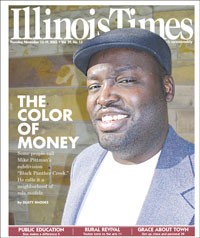

When this southeast Springfield subdivision was originally platted, the out-of-state developers called it South Grand Pointe. When developer Mike Pittman took it over, he renamed it Eastview Estates. But the yuppie style of the houses and the race of the homeowners earned the neighborhood a catchy nickname: Black Panther Creek.

Pittman claims this handle is news to him, but he takes both halves of the double entendre as compliments. As general contractor overseeing construction, he believes Eastview homes match the quality of the somewhat bigger homes in Panther Creek, the posh Westside subdivision. And as an African American who doesn't mind speaking out on racial issues, he doesn't shy away from the activist implications either.

"I hadn't heard that," he chuckles, "but that's alright."

Of course, Eastview Estates is nowhere near as financially profitable as Panther Creek. Even though the houses offer similar amenities and often the same building materials, Pittman recognizes that he can't charge Westside prices on Springfield's historically black Eastside.

Furthermore, he realizes that Eastside stereotypes effectively eliminate the majority population from his pool of potential customers (no white family has ever bought an Eastview Estates home). Among the minority population, he says, about 70 percent of households are headed by single moms who usually don't have the resources to buy such homes. About half of the remaining 30 percent have credit problems. And families that could qualify often don't want to live on the Eastside. The way Pittman figures, that leaves a potential customer base of, at most, about a thousand.

But Pittman looks for profit in places other than his bank account. The real payoff of Eastview Estates, he says, is in its power to contradict negative stereotypes of black neighborhoods.

"These are all good people out there," says Pittman. "They're making believers out of a lot of people; making liars out of a lot of people. They're changing lives and changing mindsets. That makes the city better for everybody."

You can tell a lot about a man by looking at his workplace. Pittman recently moved his businesses -- Pittman Enterprises, PitGam Enterprises, and Springfield Window Company -- into a cool 1950s office building off East Cook near Dirksen Parkway. He finds this small single-story stone and brick structure amazing, because the interior walls are also brick.

"I've never seen a building built like this," he says. "It would cost half a million dollars to build something like this."

Renovation was a simple matter of paint, carpet, and a little landscaping. The place is spacious and comfortable but otherwise devoid of frills.

In his office, plaques and certificates plaster one wall: his college diploma from what was Sangamon State University; his certificate of ordination as a deacon at Abundant Faith Christian Center; and awards from the Urban League, the Chamber of Commerce, the NAACP, YMCA, the Springfield Business Journal, and others.

Behind his desk hang a couple of African-themed prints and a poster of Muhammad Ali with the words "Fighter: One who fights, one who makes their way through struggle, one who engages in battle." Pittman calls this his "motivational" art. "Basically, it's a fight out here all the time," he says.

On top of the corner file cabinet is his black belt in tae kwon do, a sport he first took up in 1997. "It's something I've wanted to do ever since I was a kid," he says.

Baseball memorabilia covers the wall opposite his desk -- photos from the years he spent in the St. Louis Cardinals' farm system, snapshots of himself with heroes like Willie McGee, Vince Coleman, John Young, Terry Pendleton, and Curt Ford, and an autographed photo of Roger Maris hitting his 61st homerun.

Baseball brought Mike Pittman to Springfield. He was released here after five years of minor league pitching, the last few with the Springfield Cardinals. Two things persuaded Pittman to stay: Springfield's close proximity to his hometown of St. Louis, and the peacefulness of Springfield compared to the projects where he grew up.

"I used to have a list of names that I kept in my wallet . . ." he says, taking out his black billfold and looking through it. It was a list of close friends who have died violently, at last count 22, he says, rattling off the names of men shot or stabbed in taverns, on the street, on front stoops. "It was only by the grace of God that I wasn't the same statistic."

Pittman, 44, was raised by his mother, Sherline, who worked as a nurse's aide and switchboard operator at St. Anthony's Medical Center in St. Louis. She refused both welfare and money from her husband, a welder who gave up his job at Chrysler and his family to make money illegally. Her standard of living might have been poor, but her moral standards have always been top drawer.

"I was raised in a household where there was never any hate," Pittman says. "I never heard my mom swear, never saw her take a drink, never in my whole life. She always exemplified the qualities of a God-fearing woman. And even though I did mischievous things, I always knew that I knew better."

As a kid, Pittman says, he broke into buildings, stole stuff, got high, but somehow never got caught. His mom paints a different picture of Pittman's childhood, with young Mike and his brother selling newspapers, stacking soda bottles for the neighborhood store, and doing odd jobs for the Catholic priest across the street. "They did little jobs for pocket change," she says.

But whenever the St. Louis Cardinals were in town, Pittman says, he was at Busch Stadium, watching his heroes and hustling the fans.

"We had a way where we could sneak into the stadium," Pittman says. "I don't want to tell that secret because there's probably some little kids doing it now." He reaches across his desk to turn off a tape recorder, then details how he and his buddies finagled box seats at virtually every Cardinals' home game. The process he describes sounds complicated, time-consuming, labor-intensive and creative.

Pittman had a variety of money-making strategies. When the team practiced, he and his friends would run around the upper deck gathering balls, stuffing them into tube socks they could later tie onto their bikes. They would pester the players, making them promise to save any cracked bats. Some of this gear they kept; some they sold to fans willing to fork over $10 for a major league ball, $20 for a bat. And on game days, they had several ticket-brokering schemes.

"I was an entrepreneur trainee even at that young age," he chuckles. "But Mom didn't know. I told her we were working at Busch Stadium selling pennants and caps. She wouldn't have approved of what we did."

Still, he says, the time spent at the ballpark kept him from getting into real trouble. "That was like our home away from home, our refuge, in a sense," Pittman says.

He didn't get to play organized baseball himself until his sophomore year of high school. That's when his father died in a car crash and his mom received a cash settlement. Sherline Pittman, wanting to get her sons away from "city life," shopped for land in the country and bought a two-and-a-half acre plot outside of Mulberry Grove, Ill.

Pittman calls the move a "culture shock," but "probably a good move." He went on to graduate from junior college in Centralia, then attended a tryout camp for the St. Louis Cardinals. Out of 350 hopefuls, Pittman -- a left-handed pitcher with a 92-mile-per-hour fast ball -- was the only one signed.

For the next five years, he never made it out of the farm league. By 1984, he accepted the fact that his baseball career was over. If he had any bitterness, it doesn't show.

"It was hard, because this was something I had wanted to do from the time I was 9 years old," he says. "But just the mere fact that I put on a Cardinal uniform, just being on the same field with Lou Brock, Garry Templeton, guys that I idolized as a kid -- that was still a dream come true in and of itself."

Pittman's post-baseball career path has relied on humility, curiosity, a gift for getting along and workaholic tendencies. The first job he found after leaving baseball was with the Department of Revenue -- as a janitor.

"After being an athlete, it was very humbling," he says. "But I knew that wasn't my final destination. I thought, 'I'll do this for a season.' Remember, you're talking to a hustler. Whatever I gotta do, I'm gonna do it. If I've got to be a janitor, I'll be a janitor."

Next, he became a prison guard, including 18 months working at the maximum-security prison in Pontiac. In 1986, he landed his first white-collar job as manager of the Department of Transportation's accident report office. From there, he continued to work his way up through state jobs while earning his degree in labor relations at Sangamon State and starting his own business, Springfield Window Company, while buying and renovating rental properties in blighted neighborhoods.

"I was working all the time," he says. "I'd work 8 to 5, change clothes and work 6 to 11 at night."

At one point, he and his wife, Sherry, were both driving fancy cars at a cost of $700 a month. They decided it was more important to save money toward a down payment for a house. So they sold their nice cars and for two years drove a couple of clunkers -- Sherry in a Datsun decorated with four different makes of parts, and Pittman in a rusted El Camino that he had purchased for $150.

By 1995, Pittman was handling labor relations for the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency and becoming active in the local Republican Party. He supported Karen Hasara in her run for mayor, and when she was elected, she tapped Pittman to head the Community Relations Department.

Sandy Robinson, the current director of that department, worked under Pittman for two years. He says Pittman expected employees to work the same schedule he did -- "Probably 60 hours a week."

"He's a pretty intense guy when it comes to getting a project done. He'll lean on you in a heartbeat," Robinson says. "Mike doesn't play."

After three years, though, Pittman walked away from his city job, partially because he wanted political freedom.

"I like Karen, I liked working for her, and I appreciate the opportunity she gave me. But you know, there came a time when I needed to have flexibility to do those things I felt needed to be done without worrying about how somebody's going to read this. I can't let nobody control me as to what I think or what I say. I still consider myself to be a conservative on a lot of issues. But I don't consider myself to be a Republican anymore," Pittman says. "I'm really more of an independent."

The other reason he left was to pursue business opportunities with Kevin Gamble, a Springfield native who spent 10 years playing for the NBA. Together, they formed PitGam Enterprises, and launched several Eastside projects -- commercial ventures on 11th Street and the subdivision that would later become Eastview Estates.

"When I look at the Eastside, it's kind of what I felt like I was called to do," Pittman says.

About this time last year, Mike Pittman went shopping at a department store on Springfield's Westside. He was waiting outside when the store opened early to accommodate holiday shoppers. It was chilly, so he wore the new leather gloves his wife had given him as a gift just the night before.

As he made his way through the store, a security guard approached and accused him of shoplifting the leather gloves. Even now, as he tells the story, his voice rises slightly in disbelief. "How could I have shoplifted these gloves? I was wearing them before the store even opened!"

Pittman, who often wears jeans, jerseys and ball caps, tells similar stories about several local stores. These experiences convince him that, no matter how big a businessman he becomes, he will always be a suspect to minimum-wage clerks.

So it's no wonder that Pittman considers race in virtually every business decision he makes. When it comes time to buy insurance, he goes to black insurance agents. When he hires electricians, he looks for African Americans. Same goes for painters, floor-covering dealers, and drywall installers. And he decided to list the homes in Eastview Estates with black real-estate agents exclusively.

"How many black Realtors get to sell $100,000 houses in Springfield?" he asks. "They'd like to list a $100,000 house and get a 7 percent commission and have a $7,000 payday. But they don't get a lot of those listings. They just don't! So it's incumbent upon me if I'm in the position to help them put money in their pocket, I don't feel like I have a choice. It's something I just have to do."

He laments the fact that there's no black-owned bank in Springfield; he has looked in vain for a commercial loan agent of color.

"This is no slam against whites," he says, "but there are so few dollars in the African-American community, we want to make sure we do all we can to keep those dollars circulating."

His initial disappointment that no whites have moved into Eastview has been overcome by his delight at the emergence of a unique black neighborhood. He is so drawn to the notion of having his kids grow up surrounded by positive black role models that he and his wife talk constantly about leaving their own home in (white) Panther Creek to live in Eastview Estates.

"The only reason I really don't want to do it is that then I would be in a development I'm developing. I would be at work 24 hours a day. I'd be too accessible," he says.

With 31 of the 61 planned houses built and sold, he says maybe he'll buy the last house for his own family.

"It wasn't designed to be all black, but that's the way it is," he says.