Farmers and landowners in Christian County have joined more than 100 residents of Sangamon, Morgan and 10 adjacent counties to formally challenge a proposed pipeline that would carry liquified carbon dioxide from the Midwest halfway across the state for permanent underground storage in central Illinois.

Citizens Against Heartland Greenway Pipeline was granted intervenor status this summer in the Navigator Heartland Greenway CO2 pipeline case pending in front of the Illinois Commerce Commission.

Sangamon County government also became an intervenor in the case, which pits a pipeline company and ethanol and fertilizer producers incentivized by generous federal tax credits against landowners and environmental groups.

This step by the citizens' group to become a formal participant in the scheduled 11 months of ICC proceedings – as well as county-level moratoriums on pipeline-related construction being debated and enacted – are part of strategies by opponents of the proposed $3.2 billion project.

The Coalition to Stop CO2 Pipelines, which is aligned with, but separate from, the group intervening in the ICC case, is trying to engage county governments and inform Illinoisans about the potential hidden costs, environmental and public-safety hazards, and threat of long-lasting damage to croplands.

"The more people learn, the better it will be," Glenarm resident Kathleen Campbell, who lives within a half-mile of the proposed pipeline route in southern Sangamon County, told Illinois Times. "This will be the longest, largest CO2 pipeline in the United States.

"We're becoming a trash bucket for the waste of other states," said Campbell, 70, vice president of Citizens Against Heartland Greenway Pipeline and professor emeritus and distinguished scholar at Springfield's Southern Illinois University School of Medicine.

But Elizabeth Burns-Thompson, vice president of government and public affairs for Navigator CO Ventures, said the project, backed by the BlackRock global investment firm, will be safe and secure, and actually will preserve the environment long term by keeping CO2 out of the atmosphere and slowing global warming.

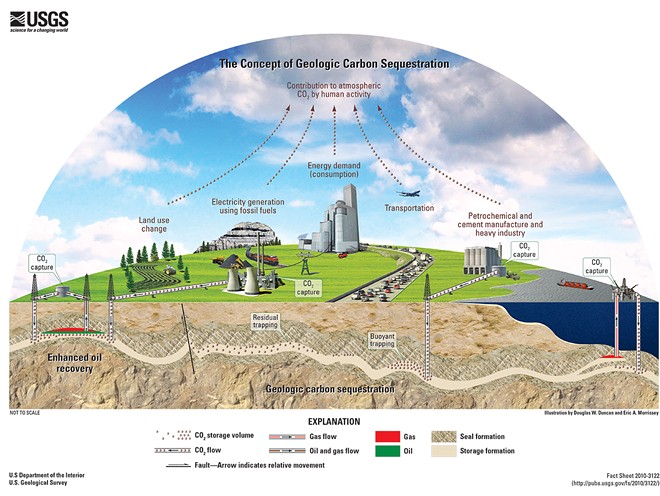

The Heartland Greenway project will be able to store up to 15 metric tons of CO2 underground each year, over a 30-year period, once operating at full capacity. That's the equivalent of emissions from about 3.2 million cars driven for one year and the amount of CO2 stored by 18.3 million acres of U.S. forests annually, according to Navigator.

The pipeline will help businesses meet mandatory and voluntary CO2 limits, support Illinois' ethanol industry and lead to spinoff businesses that could use CO2 to make fuels, chemicals and building materials, Burns-Thompson said.

And the project will result in payments to local governments in lieu of property taxes, she said.

"Carbon is an important piece to every business today," Burns-Thompson said, adding that carbon sequestration is the "biggest tool" for reducing carbon emissions.

"Carbon capture is not the only solution, but it is a pretty substantial piece of the pie," she said.

For Navigator to kick off construction as planned in 2024 and begin transporting and storing CO2 in 2025, the 1,300-mile pipeline needs approval from government regulators in Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska and South Dakota. The regulatory process in Illinois is the farthest along, with public hearings scheduled Feb. 21-24 and a final ICC decision expected in the spring or summer of 2023.

Wells for injecting the highly pressurized CO2 about a mile underground for permanent storage will need to be approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Navigator has indicated it expects that approval to happen by December 2023, though the company's application filed with the EPA hasn't yet been deemed complete. The draft application was filed this summer but isn't yet available on the EPA website. Illinois Times hasn't received an answer to its federal Freedom of Information Act request for the draft.

There's a favorable regulatory environment in Illinois for CO2 pipelines and bipartisan support in Washington, D.C., for tax credits available to companies that use pipelines and carbon sequestration to reduce CO2 emissions. President Joe Biden's Inflation Reduction Act makes those credits even more lucrative.

But pipeline opponents say there's disagreement in the scientific community over the long-term safety of Heartland's proposal to inject liquified CO2 more than a mile underground in Christian County north of Taylorville and potentially at other central Illinois locations, including Montgomery County.

"We're trying to stop it, in part, because CO2 pipelines are so dangerous and under-regulated, and carbon sequestration at this scale remains risky and unproven," said Pam Richart, co-director of the Champaign-based Eco-Justice Collaborative.

Richart leads the Coalition to Stop CO2 Pipelines and serves as an adviser to Citizens Against Heartland Greenway Pipeline.

"For whatever reason," she said, "people think this is technology worth pursuing, despite the unknowns. It prolongs the use of polluting fossil fuels and diverts funding from proven technologies, such as energy efficiency and the deployment of renewables that are far less costly and we know work."

The scope and impact of the pipeline project

The pipeline, five feet underground and between six and 20 inches in diameter, would pick up CO2 from at least 21 different industrial sources, cross the Mississippi River from Iowa, then enter Illinois' Hancock County and cover 250 miles in the state.

A fork of the pipeline would go north from the northeastern tip of Adams County and proceed through Schuyler, McDonough, Fulton and Knox counties before entering Henry County to pick up CO2 from the Big River Resources ethanol plant near Galva.

The main pipeline section would continue through Schuyler, Brown, Pike, Scott, Morgan and Sangamon County before reaching a 40-square-mile area northeast of Taylorville. The area, Navigator said, contains 25,000 acres of available "pore space" in sandstone that's part of the larger underground Mount Simon formation extending across several states.

The part of the formation in Christian County has the ability to sequester hundreds of millions of metric tons of CO2 in the sandstone, which binds with the CO2 and prevents it from moving, Navigator officials said.

There would be six injection wells and a dozen monitoring wells in the sequestration area, according to Navigator's project application.

"Navigator is highly experienced in the pipeline industry with a proven management team with over 200 years of combined industry experience in the pipeline and infrastructure industries, including technical expertise across pipelines transporting multiple commodities, and has a strong safety track record," the company's application said. "The management team works with some of the world's largest energy companies as a trusted, safe and reliable developer/owner/operator of critical infrastructure."

However, Navigator disclosed to Citizens Against Heartland Greenway Pipeline that no one on the company's management team has experience with the construction and operation of a pipeline that carries CO2 but that Navigator is working with engineering firms that do have CO2 pipeline experience.

Navigator's application said the cost of materials installed as part of the project in Illinois would exceed $140 million. About 1,600 construction jobs and 1,900 indirect jobs would be created at the peak of installation, and 30 to 35 permanent jobs would be created to operate the pipeline in Illinois, the application said.

About $32 million has been set aside for "right-of-way" payments to landowners. An additional, undisclosed amount has been set aside for "ongoing community benefit agreements with local governments along the route in Illinois" to reimburse them for property taxes on the pipeline that wouldn't be collected, based on current Illinois law.

Navigator spokesman Andy Bates said the company is pledging to reimburse farmers for the value of 250% of possible yield loss over several years, paid upfront and before any construction, regardless of whether the landowner experiences that much crop damage.

"And if anyone experiences yield losses beyond that, at any point throughout the life of the project, we are committed to making landowners/farmers whole," Bates said in a statement.

Landowners are skeptical

Landowners, environmental groups and other critics of the project have been skeptical of Navigator's claims.

The Illinois-based Coalition to Stop CO2 Pipelines was founded in January and includes the Eco-Justice Collaborative, the Sierra Club, Central Illinois Communities Healthy Alliance, Save Our Illinois Land and the Springfield-based Faith Coalition for the Common Good.

Christian County farmers have banded together in opposition, and many have formed a group called Christian County Citizens to Protect the Aquifer and erected billboards carrying the message, "No CO2 Pipeline."

"We don't want it. It's too dangerous," said Ralph Hodges, 80, a rural Taylorville resident. He owns land in Christian's Buckhart Township, which is part of the targeted sequestration area.

Nicole Lanham, 37, of rural Edinburg, said: "We honestly don't know anybody who's for it. Low-risk is not the same as no risk."

Like Campbell, Lanham and her fellow farmers have read about the 2020 rupture of Denbury Inc.'s CO pipeline near Satartia, Mississippi, that hospitalized almost 50 people and forced 300 residents to evacuate.

CO2 is an odorless, colorless gas that needs to be processed and compressed into a liquid so it can be transported. If released above-ground, it can hang low to the ground for hours and cause asphyxiation and prevent vehicles powered by gas-combustion engines from working.

Glenarm resident Campbell said the pipeline route comes within 75 feet of occupied buildings in Fulton County. The pipeline would be a half-mile from the village of Virden and within a mile of 275 homes in Glenarm, which is 12 miles south of Springfield, and as close to 300 feet from buildings in Chatham, she said.

Critics say the potential of earthquakes, other geological events and equipment failures puts their groundwater at risk, even though groundwater is far above dense rock known as capstone that Navigator officials say would prevent the Mount Simon sandstone from leaking CO2.

And opponents say inadvertent damage to farm ground and drainage tiles in the construction and placement of the pipeline could be permanent.

"More pipeline means more risk," Lanham said during a meeting when more than a dozen Christian County farmers expressed concerns about the pipeline and carbon sequestration to an Illinois Times reporter. "It has never been done on this scale before," she said.

Farmer Dean McWard, 59, of rural Taylorville, said Navigator representatives have told landowners the sequestration will "probably work. ... Nobody in this room has bought a plumbing product that is foolproof."

Sallie Greenberg, a principal research scientist with the Illinois State Geological Survey at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, said she and other scientists have worked with Archer-Daniels Midland since 2006 on a carbon-capture storage project from ADM's ethanol production plant in Decatur.

Based on that project, they have determined carbon sequestration to be safe and effective, meaning groundwater contamination and potential migration of CO2 from its underground storage site into groundwater or the atmosphere aren't happening, she said.

Greenberg noted that she and others at the geological survey, part of Prairie Research Institute, haven't studied the safety of CO2 pipelines.

Richart, from the Eco-Justice Collaborative, said CO2 pipelines put residents who live along the route at risk. She said sequestration is "evolving technology," and there's disagreement in the scientific community as to its safety, cost and long-term effectiveness. But Greenberg said she hasn't encountered such concern among other experts in geology.

Concerns about eminent domain

Christian County farmers said they are worried enough by the unknowns to oppose the project, and they are incensed by the potential for Navigator to use eminent domain to seize land if landowners refuse to grant rights-of-ways.

A 2011 state law designed to assist the now-defunct FutureGen project to capture and sequester CO2 for a proposed coal-fired power plant in Morgan County would clear a legal path for Navigator to use eminent domain for its pipeline.

Companies don't have eminent domain power when it comes to carbon sequestration sites, but pending legislation introduced in the General Assembly by state Rep. Thomas Bennett, R-Gibson City, would essentially grant eminent domain for sequestration if a majority of landowners at a site agreed to easements and pore space. Bennett hasn't returned phone calls from IT seeking comment.

Burns-Thompson said Navigator might push for passage of this legislation, but she said eminent domain will be a last resort for Navigator for pipeline and well construction.

"'Voluntary' makes the most business sense across the board," she said.

Richart said opponents of the pipeline have been working with township officials, village boards and county boards and are starting to reach out to members of the Illinois General Assembly.

State Sen. Steve McClure, R-Springfield, whose new Senate district includes most of Christian County, said: "I am meeting with constituents and others to discuss the project this week and take very seriously the concerns that are being shared with me about the project."

The offices of U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Springfield, and Gov. JB Pritzker, a Democrat, didn't respond to requests for comment.

Karen Brockelsby, 67, treasurer of Citizens Against Heartland Greenway Pipeline, said, "Basically, we feel assaulted by big businesses out here.

"My family has farmland both along the pipeline and in the proposed injection site ... and we are very concerned about what damages may occur to water sources and cropland if the CO2 doesn't stay where it is when pumped beneath the capstone," the rural Edinburg resident said.

"There are other instances in Illinois where natural gas has escaped to the surface from under rock that was supposed to hold it in place," Brockelsby said. "These areas have ongoing water and soil contamination with no real solutions available."

Her husband's cousin, Steve Brockelsby, 67, of rural Taylorville, said he and other farmers have contacted landowners in the designated sequestration area, and almost 90% have told them they oppose the project and won't agree to financial agreements that would give Navigator the rights to pore space under their land.

"We want our door locked," he said. "We want them to leave us alone."

Steve Brockelsby said many residents of Taylorville, a county seat of about 10,800 people in a county of 32,700, aren't concerned about the project and see it as a "farmer problem." But a contaminated aquifer affects city and rural residents alike, he said.

On the ICC website, Illinois residents opposing the project have voiced concerns.

Many supporters of the pipeline have posted the exact same comments for case 22-0497. Their comments read, in part: "As a leader in the biofuels industry, Illinois is uniquely situated to spearhead efforts of carbon management and the race to carbon neutrality. ... By providing an economic way to reduce the carbon intensity of Midwestern products, Heartland Greenway will help expand the market potential for corn-based ethanol and other value-added goods while also creating valuable employment opportunities for highly skilled laborers, and generate ongoing increased tax revenues for communities across the footprint."

Elected officials becoming involved

The Christian County Board voted in May to impose a six-month moratorium on issuing special-use permits for underground CO2 facilities. And the Sangamon County Board voted unanimously Oct. 11 to enact a moratorium on "permits or other grants of authority to construct any carbon-dioxide pipeline ... prior to May 1, 2023."

Sangamon County's intervention and moratorium "are meant to express, in particular to the Illinois Commerce Commission, the deep concerns of the citizens in our community who may be affected by the proposed construction of this pipeline," a Sept. 1 statement from county officials said.

These are the types of actions being promoted by the Coalition to Stop CO2 Pipelines, Richart said.

The coalition recently obtained a legal opinion from Ancel Glink, a Chicago-based law firm that has offices throughout central and western Illinois. According to the legal opinion, counties have the authority to regulate CO2 pipelines, including setbacks.

The opinion said that while counties don't have the ability to prohibit CO2 pipelines or regulate design, a county can issue a moratorium on pipeline construction tied to the actions of a federal agency known as the Pipeline Hazardous Materials Safety Administration.

That agency is updating rules governing CO2 pipeline construction, and the update should be complete by October 2024, Richart said.

It's possible that the Illinois Commerce Commission could overrule a county's zoning ordinance and moratoriums, she said.

But having a zoning ordinance in place "would help the ICC understand a county's concerns regarding Navigator's project and how it affects public safety, infrastructure and the economy," she said.

If the ICC ends up approving the pipeline, the commission could ensure that local counties receive funding from Navigator to mitigate these issues, as well as require Navigator to provide equipment that would be needed in emergency services, Richart said.

The statement from Sangamon County said officials understand "that ultimately it may be determined, either through continued ongoing legal research, a ruling from a court of law, an ICC ruling or a change in state law that it has no role in regulating the Navigator pipeline."

But the statement said intervening is a "reasonable and responsible approach."

Other potential locations for sequestration

It's unclear whether the opposition from Christian County landowners has altered Navigator's plans. Burns-Thompson said the company is still focusing on Christian County as a potential CO2 sequestration site. But she also said the geology "is pretty robust in many areas. It's not just Christian County. We want to make sure that we're having the opportunity to match both the geology and the landowners who are interested in the project.

"We do have the opportunity to get, and are getting, very vast interest in the project, both from the pipeline side as well as the sequestration and pore space," she said.

She acknowledged that Navigator officials are talking with officials in a Montgomery County, immediately south of Christian County, as well as government officials and landowners "all over central Illinois."

Burns-Thompson wouldn't be more specific as to the locations but said, "We've had very positive feedback from these folks." She said Navigator has been "very successful" in securing leases for potential pore space and CO2 well sites.

Campbell said Navigator apparently is looking at potential sequestration sites in Sangamon County. She said she has documentation that Navigator offered to pay the owner of land near Pawnee for a proposed CO2 well site, but the landowner turned the company down.

Montgomery County Board Chairman Evan Young said at least one landowner in the county's far-eastern Audubon Township has signed a contract with Navigator for rights to build a well and to use pore space. Another landowner is contemplating an offer, he said.

Young said Navigator officials made a presentation to the board in September to propose an agreement that would pay the county at least $1.5 million per year for 30 years in lieu of property taxes and in exchange for the county not opposing the pipeline and sequestration sites.

Montgomery County is dealing with a $1.5 million budget deficit based on a total general fund budget of $6 million per year. The Navigator money could come in handy, but the County Board is analyzing and weighing the proposal, Young said.

"We're wanting to have the growth, but we want to be responsible for the citizens of the county," he said. "I think right now most of our board members are on the fence and trying to learn more. I've only had one person really firmly against it. Some citizens have voiced concerns against the project, and some are for it."

If Navigator were interested in sequestration sites outside Christian County, the company could amend its EPA application, company spokesman Andy Bates said.

Because Navigator doesn't have a "clear path" to a specific site for CO2 sequestration, Champaign lawyer Joseph Murphy, who is representing the citizens group, asked an administrative law judge presiding in the Navigator case to dismiss the case for now. Otherwise, Murphy said in a Sept. 1 meeting with the judge and other intervenors, the project would create a "pipeline to nowhere."

The judge didn't rule on that informal request, which Richart said could become a formal motion in the future.

Burns-Thompson said the pipeline and sequestration sites need to be worked on at the same time. Doing one without the other is "not a feasible way to do development," she said.

Campbell, the retired SIU professor helping to lead the charge against the project, said she feels "more optimistic than I did three or four months ago" when there was little publicity and less awareness.

She said she is an audiology researcher, not a geologist, but she remains undaunted in a mission being carried out almost entirely by volunteers.

"This is our county. This is our state," she said. "We don't belong to Navigator."

Dean Olsen is a senior staff writer for Illinois Times. He can be reached at [email protected], 217-679-7810 or twitter.com/DeanOlsenIT.