George H. Ryan has faced some harsh critics during his 87 years of life, much of it spent in the public eye. But there was no tougher crowd than the roomful of murder victims' families that he invited to the Illinois Executive Mansion in 2002.

"They were bitter. They were terribly angry," Ryan said. "I stood at the podium and they threw stuff at me and raised hell with me."

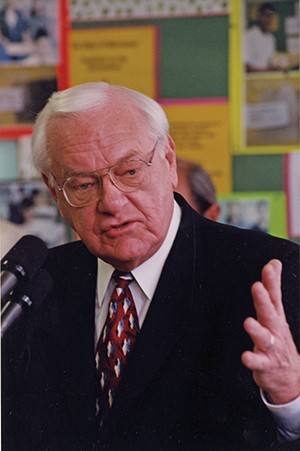

Ryan, who was in the waning months of his one term as Illinois' 39th governor, was considering the fate of more than 100 prison inmates on the state's death row. He had been moved by the high-profile case of an innocent man who had spent 18 years awaiting execution in Illinois, and stood poised to make a monumental decision that would change the state's criminal justice landscape for generations.

Ironically, Ryan is most often remembered for his own troubles with the criminal justice system that ended with him serving five-and-a-half years in prison. He decided not to run for reelection in 2002, largely due to the highly publicized investigation that would ultimately result in his conviction. That left Ryan with a few precious months to accomplish what could form the legacy of his term in office.

"I wanted to do other things with my time in the governor's office, but I got waylaid with the death penalty," Ryan said.

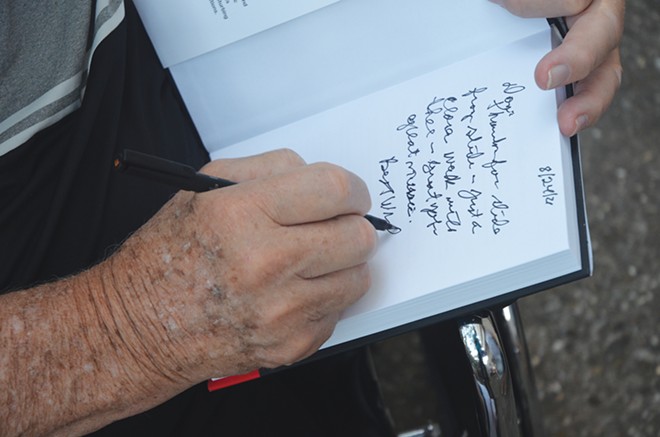

That issue is the focus of Ryan's book Until I Could Be Sure: How I Stopped the Death Penalty in Illinois. The book was published in 2020, and Ryan held a private reception and book signing for friends and former colleagues recently in Springfield. He discussed the death penalty, his own time in prison and his life in retirement.

"How does that happen in America?"

"Before my time in office and as an officeholder I strongly supported the death penalty," Ryan said. "It took some time for me to change my mind about keeping it in place."

Ryan, a Republican, was faced with the prospect of an execution shortly after he took office in 1999. The governor's role in an execution is to consider any final executive clemency requests that are filed on behalf of an inmate. Ryan did not grant clemency for Andrew Kokoraleis, who was put to death on March 17 of that year.

"That guy was terrible. He and his gang used to drive down the streets of Chicago and pick up young women and mutilate them, rape them, kill them and throw them back in the street," Ryan said. "All of my staff and everybody wanted me to go ahead and execute the guy and I said I really didn't want to do it, but in the end I looked at it and he was guilty and did a lot of really bad things."

"So we executed him. I did that and I'll have to live with that for the rest of my life," Ryan said. "But I thought I did the right thing at the time."

That same year, Anthony Porter was exonerated after having spent 18 years on Illinois' death row for a double murder. Ryan had granted Porter a stay of execution that gave Northwestern University journalism students time to hire a private investigator, who found the real killer. Porter's release from prison received extensive media coverage.

"I was at the Executive Mansion watching the news and here comes this guy with a big grin on his face. He has just been released after being in jail for 18 years for killing those people," Ryan said. "I said to (my wife) Lura Lynn, 'How does that happen in America?' How do they keep a guy in jail for 18 years on death row and then tell him he's not guilty, you can go home now?"

The Porter case triggered Ryan's interest, and a follow-up investigation by the Chicago Tribune about the state's death penalty statute and its implementation made Ryan realize "how bad and corrupt and rotten the death penalty was and I agreed it didn't work."

Ryan personally reviewed the cases of more than 100 Illinois inmates on death row. He appointed a commission to examine and improve the state's death penalty statute to a point that Illinois would not execute an innocent person, and that commission came back with 85 recommendations for legislation.

"Well, it was an election year and (Senate President) Pate Philip just buried the legislation altogether, because he was a solid guy with the death penalty," Ryan said. "(House Speaker) Mike Madigan managed to pass just one piece of the recommendations, and that was that all people in death penalty cases had to have their confessions videotaped."

"At that point I only had a few weeks left in office. I couldn't get anything done, it was an election year, and nobody wanted to look like they were soft on crime," Ryan said. "I could leave office and let the system go on and maybe three guys get executed who are innocent. Then I would have asked myself, 'Why the hell didn't I do something about it.'"

That's when Ryan began to think there was only one safe way to prevent the execution of innocent people. He began discussing the possibility with his staff of commuting all death row inmates' sentences.

"It was a very intense four-month period"

"There was division in the Governor's Office," said Dave Urbanek, press secretary and later director of communications for the Ryan administration. "There was political division, there was policy division, and there were a lot of Republicans who were like, 'What are you doing? The death penalty is one of our staple issues.'"

"They said this isn't what Republicans do. But George said, 'Well, this is what decent people do,'" Urbanek said. "He actually did have his hand on the switch. And the way the system was set up it was unfair and it wasn't working."

Brad Cole was Ryan's deputy chief of staff.

"The legislative leaders weren't on board, most of the people of his own party weren't on board. Eliminating or placing a moratorium on the death penalty was not exactly a Republican platform issue at the time," Cole said. "There were and are friends that have probably let this issue or some other issue influence their opinion of George. But there are a lot of others that still have great admiration for him."

Few people were busier than Mark Warnsing during the waning days of 2002. He was the administration's deputy counsel for public safety and advised the governor about all of the facts and legal issues on each executive clemency case, which are normally handled one at a time. As Ryan's term was ending, there was an avalanche of more than 100 clemency cases at once.

"A lot of the lawyers for these death row guys picked up on the fact that the governor may want to start considering these cases," said Warnsing, who had assisted on death penalty cases during an earlier career as a prosecutor. "It was a very intense four-month period. Addressing everybody on death row at the same time was a monumental step and a rather daunting thing to even try to contemplate."

Ryan ultimately decided to commute the death sentences of everybody on death row to life in prison, except for four individuals whose sentences were commuted to time served and were released.

"What I did with the death penalty

put an X on me."

Ryan's death row decision came as federal prosecutors were building their case against him and 78 other state officials. The investigation began while Ryan was Illinois' secretary of state. Six children were killed and their parents severely injured in a Wisconsin crash caused by an unqualified driver who had obtained his license through bribes made to Secretary of State officials. The investigation scope widened to include things that occurred while Ryan was governor.

Ryan was indicted in December 2003 on 22 counts, including racketeering, bribery, extortion, money laundering and tax fraud. He was defended pro bono by Winston and Strawn, the law firm managed by James R. Thompson, the former governor, with whom Ryan had served as lieutenant governor.

April 17, 2006, a jury found Ryan guilty on all counts. He was sentenced to six and a half years in prison. Ryan served five and a half, entering federal prison on Nov. 7, 2007. His wife of 55 years died in 2011 while Ryan was incarcerated.

"Here I am in prison and my wife died. It was terrible, I couldn't do anything," Ryan said. "They gave me an opportunity to go visit her but she was almost dead when I got to the hospital at midnight. Then they wouldn't let me go to her funeral. I wasn't doing anything in the prison, and I missed her burial."

As tough as that situation was, Ryan said it was nothing compared to the plight of the inmates on Illinois' death row during the last days of his administration.

"There's no comparison. I was in a camp, there were no bars, the guards didn't check to see if you were in bed at night," Ryan said. "To compare it to death row, I couldn't do that."

The prison at Terre Haute where Ryan was incarcerated housed the federal death row, but Ryan said there were no executions while he was there.

Ryan still feels he got a "raw deal" with his conviction and imprisonment, and, "What I did with the death penalty put an X on me," Ryan said. "Pretty much every prosecutor and police officer in the state were upset and told me how bad I was."

But Ryan still has no regrets about his mass executive clemency actions.

"It was the right thing to do," Ryan said. "I would do it again."

Mike Murphy of Springfield served as press spokesman when Ryan was the lieutenant governor and during his first term as secretary of state. Murphy was one of many people who reconnected with Ryan during his recent Springfield book signing.

"George Ryan as I knew him was not hardhearted or a conservative for that matter, so I was not surprised that he did the right thing about the death penalty," Murphy said. "Unfortunately he was going through some other things at the time that cast some ill light on his tenure, but I'll never be able to thank him enough for his position on the death penalty."

Ryan's late 2002 actions eventually led to legislation that was signed on March 9, 2011, by Illinois Governor Pat Quinn to abolish the death penalty in Illinois. All 15 death row inmates in the state had their sentences commuted to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

"I have no conscience problems."

Several years ago Ryan and Urbanek started drafting a book about Ryan's career as a state representative, speaker of the Illinois House, lieutenant governor, secretary of state and governor.

"I called Scott Turow, he's a friend of mine and has written a lot of good books," Ryan said. "After he read what we put together, he said, 'You don't want to write this kind of book, you want to write a book on the death penalty. That's the story you want to tell.'"

Ryan collaborated with former Chicago Tribune writer Maurice Possley, "who used to kick the hell out of me all of the time when I was governor," and the book Until I Could Be Sure was the result.

Ryan still lives in his hometown of Kankakee but is frequently in Springfield visiting family. He has six children, 17 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren. Ryan is still acknowledged throughout Illinois.

"I walk down the street or I go to restaurants and people recognize me and come up and say hello," Ryan said. "They are all very generous and kind. I haven't had anybody really get after me."

"Life has been good, my family is healthy, I have a lot of grandkids, and I'm now living an old man's life," Ryan said. "I have no conscience problems with what I did when I was in or out of office."

David Blanchette is a freelance writer from Jacksonville. He was part of the team that worked with Governor and Mrs. Ryan on the development of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, and later served as downstate press secretary for Governor Pat Quinn.