His Internet name was "poppa bear," a chubby, sprawled-out-naked-on-the-couch elderly man attracted to slim, muscular males, ages 20 to 40. In the real world, his name was Father Francis Gera, a priest at Holy Dormition Byzantine Catholic Church in Ormond Beach, Florida.

Gera was bold, or dumb--most likely both. The e-mail address he used at gayvill.porncity.net was the same he gave out to parishioners. Last winter one of them performed an Internet search of Gera's e-mail address and up popped poppa bear's personal ad.

The parishioner alerted Gera's bishop. When the bishop didn't respond, the church member contacted Stephen Brady of Petersburg.

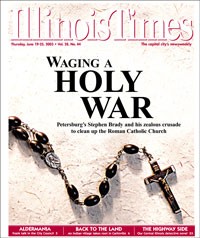

Brady heads Roman Catholic Faithful, a group he created in 1996 to address his concerns about the Springfield Diocese, which includes Catholic congregations throughout central Illinois. Brady, who earns most of his income running Leo's Pizza in Petersburg, has since expanded his field of battle. Roman Catholic Faithful's Web site, www.rcf.org, is a disorganized mixture of news updates, warnings to Catholic leaders, press releases, and links to church scandals all over the world. Brady claims his work has forced the resignations of six priests and two bishops, in dioceses from Dallas to South Africa. In 1999, he created headlines when he exposed a Web site where several dozen Catholic priests swapped stories of their sexual exploits, occasionally involving young children. On any given day, Brady gets dozens of calls and letters--and a hundred e-mails--from alleged victims of clerical wrongdoing, or from those who know about it.

When Brady learned about Gera's secret life, he was appalled. He logged on to the Web site Gera used, and propositioned him. Gera took the bait. In February, Brady wrote to Gera's bishop, threatening to go public with the pictures and the ad. Gera was quickly removed from the ministry. Brady made headlines once again.

"This guy in Catholic terms is a danger to the faithful," Brady told the Orlando Sentinel. "He obviously can't believe what the church preaches." The newspaper identified Roman Catholic Faithful as "an Illinois-based group dedicated to fighting 'corruption within the Catholic hierarchy.' "

Roman Catholic Faithful began as a small group of Brady's friends at St. Peter's Church in Petersburg. Within a few years, it attracted about 300 people from the area. Today, RCF claims more than 5,000 members from across the U.S.--as well as a few abroad--and annual donations of about $200,000, including a recent $10,000 donation from the California-based Do Right Foundation.

RCF's main mission has been to root out bad priests involved in sexual scandal. Brady is blunt: "We are in the business of destroying lives, but lives that need destroying."

In January, the New York Times found that more than 1,200 priests have been accused of sexually abusing more than 3,000 people. The Catholic Church continues to respond to such alarming numbers more like defiant litigants than, well, the representatives of Jesus Christ. As Brady says, "This is a church whose leaders have to vote on whether a child rapist can continue to wear the cloth."

As the Catholic Church continues to wrestle with scandal after scandal, Brady has always been available for an interview. In one 30-day period last spring, he was quoted in the Los Angeles Times, south Florida's Sun-Sentinel, the Chicago Tribune, and the Washington Times. He has traveled to protests, speaking engagements, and radio talk shows from California to New York, pursuing his crusade. He has become known on the Internet as the Pizza Man from Petersburg. And while the World Wide Web has largely been responsible for Brady's success, he points out the Internet has also been responsible for getting many priests into trouble.

Brady, who turns 53 in July, has been a well-known figure in these parts at least since December 1993. That's when Petersburg City Council member Jim Haddick was arrested during the early morning hours for trying to cut down a pro-life sign Brady had erected at the southeastern entrance of town. Subsequently Haddick resigned from the council. The story was picked up by the local press as well as the Illinois Family Institute, a partner of the conservative Christian organization Focus on the Family. The following year Brady was banned from Peterburg's Porta School District, after embarrassing a counselor about a sex education survey his oldest son took home.

Leo's Pizza is popular, but now only among non-Catholics, says Brady. Ever since RCF got off the ground, some area Catholics have stayed away from Brady and his pizza. He is disliked primarily for his aggressive pursuit of former Springfield Diocese Bishop Daniel Ryan and his complaints that the local Catholic hierarchy has been covering up alleged misdeeds by Ryan.

Springfield bishop from 1983 to 1999, Ryan retired shortly before a lawsuit was filed claiming he had helped to cover up another priest's abuse of an altar boy. Brady had already been leading an over-the-top campaign to oust the bishop, mailing 30,000 anti-Ryan postcards and staging street-corner protests. After holding a press conference at the Springfield Hilton, Brady was roundly criticized for having little evidence to back up his assertions.

Since then, other young men have come forward, claiming to have been targets of sexual advances by Ryan himself. Three are referred to in the 1999 lawsuit--and one has even passed a polygraph test. For a time Brady was the only person who took their claims seriously, even hiring a private detective to help verify their stories. Along the way, he compiled a massive amount of information about pedophile priests, which he fed to lawyers, the FBI, the press, and the Office of Child and Youth Protection, a lay panel established by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops to investigate the sea of sexual abuse scandals in America's largest church.

Ryan has always insisted on his innocence. In a February 1997 issue of the diocesan paper, Catholic Times, Ryan wrote, "I received a message from Mr. Brady, containing several vague, unfounded accusations against me if I did not very soon resign my pastoral office. I categorically deny his accusations." Then late last year, two years after retiring as bishop, Ryan agreed to suspend all public ministry work.

Those familiar with Brady aren't always willing to speak about him on the record. One Catholic attorney says, "He has tapped into some amazingly well-informed sources. He was among the first to identify [pedophile priests] as a problem that was being covered up by the American Bishops as a group.

"However, he is such an idiot that I'm sure God is leading him. He has no natural ability to identify or interpret facts. Despite that, I guarantee that he saw this problem when no one would have dreamed of it."

As for others who've run into Brady, they're either brief or guarded.

"I'm not going to get tied up in this mess again," says James Haddick, the sign-cutting former Petersburg alderman. "You do what you have to do. It was a mess for me and my family."

Kathie Sass, spokesperson for the Springfield Diocese, once dismissed Brady as "sad and angry." Today she sticks by her words: "I pray for Mr. Brady."

Brady says he needs these prayers, as well as "a good priest and a good parish. There isn't one." Brady and his family--he and his second wife, Jo Ann, have seven children--no longer attend St. Peter's, he says, because "the people there can't stand us." Every Sunday he drives more than 20 miles out of town to attend mass.

"Being Catholic is supposed to mean something," he says. "There's no other situation I know of in which someone can get away with all this. Who on earth expects anyone to respect the Catholic Church?"

In the early 1970s, Brady was living with his family in Hammond, Indiana. Between high school and his first year at Purdue University in Calumet City, he worked menial jobs at Rand McNally and LaSalle Steel. During his first year at college, he was drafted and served as an Army M.P. guarding nuclear weapons sites in the U.S. In 1974, he left the service after two years, but not for Hammond or Calumet City.

He was tired of northwest Indiana, urban life, smog, and factory work-- during his last week at LaSalle a piece of steel struck him on the head and knocked him unconscious. He wasn't going to go back to that. Brady, who was born in Decatur, had fond memories of his grandfather's farm near Athens and headed for the quaint little town of Petersburg. He found a job at a fertilizer company, and then quit to start his own construction firm.

Brady wanted to settle down with his wife and start a family, but he felt something was missing from his life. He began to think it was religion. His parents were Catholic but they hardly ever went to church. Brady paid a visit to his parish priest, Father Stanley Swaitek, a no-nonsense, conservative cleric. He was looking for help to raise his family right.

Swaitek became Brady's spiritual advisor, providing encouragement and the occasional reprimand. He took Brady to task for having married outside the Catholic Church. Then one day in 1977, Brady came home to an empty house. He says he later learned his wife was having an affair with one of his employees. He pursued custody of his one-year-old daughter, but lost. "I was devastated," he says. "The child meant everything to me. We keep in touch, but not all that much." By 1979 Brady had moved on and married Jo Ann in a church service.

In 1983, when Dan Ryan became bishop, Father Swaitek retired, "forcibly," according to Brady, who suspects Ryan wanted to rid the diocese of "hardliners." Swaitek died in 1987.

"I didn't know if I wanted to be a Catholic," says Brady. "I was drawn to Father Swaitek and spent a year learning about the faith from him. He was an honest man, a man's man. I loved him. He was kind, but not a pushover. He'd refuse to give me communion if I wasn't living right."

By the early 1990s Brady's five oldest children were attending public schools in Petersburg. In 1994, his oldest son, Phillip, began high school; one day he brought home a survey asking questions about his sexual behavior. Brady was livid. He already had numerous interactions with the school district about his right as a parent to keep his children out of sex ed classes in which Planned Parenthood--to him, the nation's number one baby killer--told students about its services. He thought the survey's questions were inappropriate; he drove to the school and asked the counselor responsible for the survey how many times a week she masturbated.

"I argued that since the children were being asked similar types of questions that she should be required to answer them as well," Brady says. Of course, the students were supposed to answer the questions in private, not in front of people at the school's front office.

"I didn't want the teacher to answer, but only to realize how embarrassing the question was," he says.

After the exchange, Brady didn't stick around. District officials, though, called the police, who questioned Brady about the incident. Nothing happened, except, a few days later, Brady received a letter from the district superintendent informing him that the school board had banned him from district property for the remainder of the school year.

Still, Brady says the situation was especially difficult for his son Phillip.

"Your dad's a faggot" was written on the chalkboard in his son's classroom, Brady says, and people were calling Phillip a "Jesus Freak." Eventually Brady pulled his children from the schools. His wife has been home schooling them--their youngest is eight--ever since.

"I was trying to do what I thought was right," Brady says. "But I damaged the relationships between my oldest children and me." Phillip soon fell in with a bad crowd, he says. Now Brady won't even allow him near the rest of his children. He still talks with Phillip from time to time, but sighs heavily when speaking of him.

"I've made mistakes," he says. "As a parent, I don't know all the answers. You feel like a failure to a certain degree."

During his problems with the public school system, Brady began to find fault with his fellow Catholics, people at church who also taught his children and sat on the school board. The decisions they were making, such as inviting Planned Parenthood to teach about contraceptives and abortion, were directly in conflict with Catholic teaching.

In 1994, Brady sought help from the diocesan leaders. Maybe the bishop and other priests can confront these people, encourage them to uphold the church's teachings, he thought. But after meeting with a priest who discouraged Brady from being a troublemaker, he grew disillusioned. The meeting marked a turning point for him.

"From then on," Brady says, "I formed the belief that the Springfield Diocese was not living in accordance with the Catholic faith. I don't care about what one person believes or the next person believes or what people do in their own bedroom, but you put on a collar, and you're obligated to defend the faith. Bishops and priests have the responsibility to uphold the faith.

"RCF started because of problems with the school board," says Brady. "It promoted Planned Parenthood, promoted abortion, condom use, promiscuity, and homosexuality as an alternative lifestyle. This was doubly difficult because the people who were Catholic happened to be the biggest problems."

I had my first encounter with Stephen Brady last December, after writing a profile of Patrick Baikauskas, a former gay activist and Republican who once lived in Springfield and recently joined the seminary to become a priest. I thought the story was about spiritual transformation; Brady considered it further evidence of the church's demise. When the article came out, he raised enough noise about it that he almost got Baikauskas kicked out of the seminary. At Brady's office, the Baikauskas story has its own file.

Brady says he's accepted the likelihood that Baikauskas will one day be ordained. He'd still like Baikauskas to publicly renounce his "gay activist past" and embrace the Catholic teaching on homosexuality, which accepts the orientation but forbids the lifestyle.

"I am not sure what he wants me to denounce," responds Baikauskas. "My working for services for people living with AIDS? My working to secure equality in the workplace and housing for gay men and women? The church is not against these things. Neither is the church opposed to people being in love. So I cannot denounce any of those things."

"The problem isn't Baikauskas's orientation," says Brady. "But especially in the current climate, most victims [of pedophile priests] are post-pubescent boys. By definition, then, homosexuality is the problem. But we have no right to persecute homosexuals."

Fred Nessler, a Springfield attorney who has successfully represented victims of sexual abuse by priests, talks with Brady "a few times a year." Over the course of Nessler's own investigations, he says, he's contacted Brady "to see what he knew." Nessler is not a Catholic but a member of Calvary Temple, an Assembly of God church in Springfield. He describes Brady and himself as "Ten Commandment" men.

"He and many other conservative Catholics are very upset and offended. He's a very faithful, forthright, Catholic man who appears to want to clean up the house. If you're someone who believes that biblical beliefs are found to be true, you have to admire him."

That he isn't admired by everyone is plain to Brady. But his sense of this has increasingly grown during the last few years. He is installing security cameras after some minor vandalism at RCF headquarters. He's received two death threats: one he came across on the Internet and one was sent to him in the form of a letter. In 1998, Brady purchased a bulletproof vest not long after detectives interviewed him for four hours when a priest was brutally murdered in Dane County, Wisconsin. The priest, Alfred Kunz, had been providing information to Brady and RCF about specific priests and Catholic officials. The murder remains unsolved.

Brady is tempted to leap to conclusions. He's also considered quitting.

"Many a day I have wanted to walk away from this. Right about that time, I get a phone call. People call me for marital counseling. I get calls from priests, one who bawled like a baby. Stories like you can't believe them."

So Brady shows no signs of slowing. He puts in about 50 hours a week at RCF's office, an old school building in downtown Petersburg he bought for $155,000 in the late 1990s. He tried to start a nondenominational Christian school there, but it never got off the ground. He recently started taking a small salary from RCF, about $24,000 a year--he is the organization's only paid employee. When he's done for the day, at around 4 p.m., he heads over to Leo's, six days a week. On Sundays, he rests.