“For some people, it is a life-changing event,” said Dr. John C. Martin, associate professor of astronomy-physics at University of Illinois Springfield, regarding the upcoming solar eclipse at approximately 1:20 p.m. on Monday, Aug. 21. “I’ve been warned that once you experience a totality you’re going to want to start traveling to see more, because it really is an out-of-this-world, not-everyday type of event.”

The “totality” Martin is referring to is the technical term for what people in the path of Monday’s eclipse will witness: a complete blocking out of the sun lasting a little more than two minutes. A solar eclipse occurs when the moon moves between the earth and the sun. “From the perspective of a point on the earth in the moon’s shadow, the moon is blocking the sun,” Martin explained. “The moon’s shadow is small, compared to the size of the earth, so only the people in the moon’s shadow are able to see the solar eclipse, which is the reason for the narrow path running from West Coast to East Coast.”

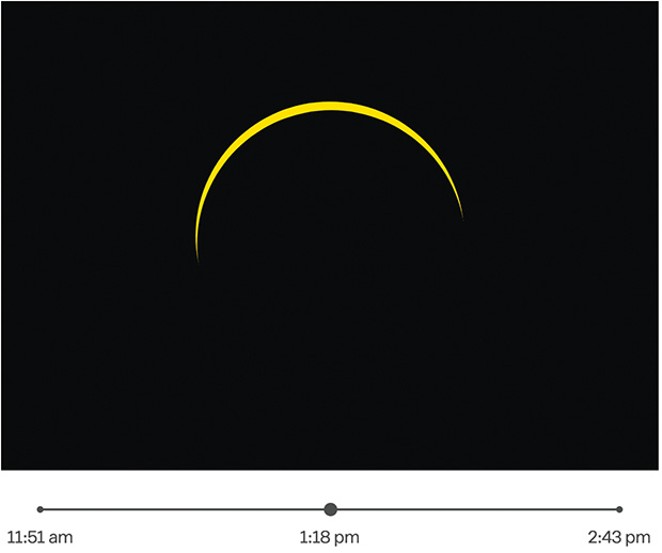

For those unable to take the day off or make the trip south, Martin says that from Springfield, at about 1:18 p.m. Monday, 96 percent of the sun will be covered. “That’s not bad,” he said, “but if people want to get the full effect, I encourage them to move all the way into the shadow. Having 96 percent of the sun covered means four percent is not covered.” He went on to explain that the amount of light reaching your eyes from just four percent of the sun is the equivalent of having a 1,000-watt halogen bulb held two feet from your face. “So, still pretty bright,” he laughed.

The difference between seeing a partial and total eclipse is stark, according to Martin. “In a total eclipse the sun is completely covered,” he said. “It’s dark like night, animals start to behave like it’s nighttime and start to go to sleep, you can see the stars, the temperature drops very suddenly because the sun isn’t warming you up anymore. It’s really a very different experience even compared to 98 or 99 percent coverage.”

Although the Carbondale area will officially see the longest duration of totality, hardcore eclipse-o-philes know that length isn’t everything. “This time of year in Carbondale you have about a 50-50 chance of the skies being clear,” said Martin. “There are no refunds if it’s cloudy.” He explained that some dedicated astronomy enthusiasts – himself included – will travel to a point within short driving distance of several places along the shadow’s path. Then, about six hours before the eclipse they’ll check the weather radar for the location with the smallest amount of cloud cover and head there in time to experience the totality.

A high-end estimate of two minutes, 40 seconds, doesn’t seem very long as events go. Indeed, the totality will not exceed the length of the average pop song on the radio. It is hard to imagine traveling many miles to see a musical group play only their latest hit single and then immediately go home, for instance. The difference here, of course, is the cosmic nature of the experience.

Essayist Annie Dillard dramatically described her impressions of a 1979 totality in her essay “Total Eclipse” (included in the book Teaching a Stone to Talk): “The sky snapped over the sun like a lens cover. The hatch in the brain slammed. Abruptly it was dark night, on the land and in the sky. In the night sky was a tiny ring of light. The hole where the sun belongs is very small. A thin ring of light marked its place. There was no sound […] There was no world.”

On May 5, 840, Emperor Louis of Bavaria, the son of Charlemagne, witnessed a solar eclipse and, according to history books, quickly died of fright.

Even if the experience is unlikely to scare you to death, it is paramount for those planning on viewing the eclipse to take proper eye safety precautions, according to Martin. “Do not look at the sun with your unaided eye, especially not through a telescope,” he said. “Even when the sun is 96 percent covered, it is still bright enough to permanently damage your eye.” He recommends using a pinhole camera or solar-viewing glasses instead of looking directly at the sun. Some school districts in the eclipse’s path, including those in Edwardsville and Carbondale, will not hold classes that day, at least partially to avoid liability for damage to students’ reckless eyeballs. Other reasons given for school closings on Monday include things like avoiding traffic gridlock.

As for the science of it all, Martin said there is not very much new scientific information to be gleaned during an eclipse. “There are some historic, well-known experiments that can be reproduced – which are probably a lot easier now with electronic detectors,” he said. He gave Stonehenge as an example of an ancient astronomical calendar which people in the distant past used, along with their observations of the sun, in order to predict eclipses, not exactly breaking news, science-wise. “A thousand years ago, though, if you could predict an eclipse, you were probably going to become the richest person in town because everyone would think you’re a god,” Martin chuckled.

For the most part, though, Martin characterizes Monday’s totality as more of an awe-inspiring event than a scientifically fruitful one. “After all, it’s not every day that turns into night in the middle of the afternoon.”

Scott Faingold can be reached at [email protected]