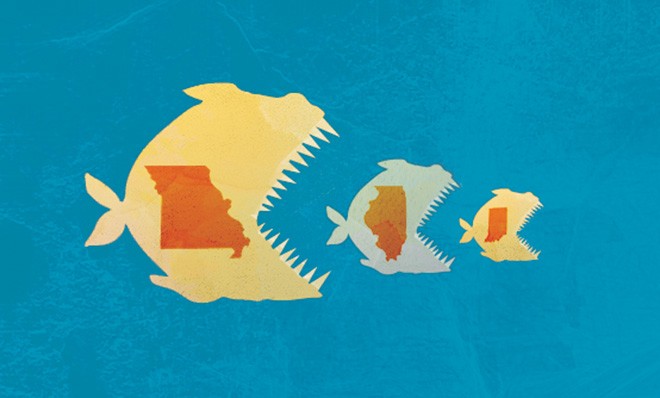

As sponsors try to get the General Assembly to once again consider the issue of expanding riverboat casino gambling, there is growing concern about cannibalism in Illinois. New young casinos like to eat old established casinos, while Missouri casinos eat Illinois casinos and Illinois casinos eat Indiana casinos. Legislators don’t know how to keep gambling revenues expanding, except by creating more new casinos and other new gambling opportunities, which will then eat the others alive. Sponsors would like to revive the bill that passed the Senate last spring to create four new riverboat casinos, including one in Danville, plus a huge new land-based casino in Chicago, but there is a problem.

In its most recent report on wagering in Illinois, the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability spells it out: “There is only so much gaming revenue available before an area becomes saturated.”

For example, July 2011 saw the long-awaited opening of the 10th Illinois riverboat casino at Des Plaines. It was a huge success, with four million admissions a year in its first two years. In the year that ended June 30, the new casino generated $410 million in receipts, making it the highest revenue-generating riverboat casino in Illinois. Meanwhile, the four Illinois casinos near Des Plaines have seen their receipts drop nearly 18 percent, $150 million, since the new casino opened. The casino at Elgin, the closest to Des Plaines, is down nearly 30 percent over the two years. The five nearby Indiana casinos have declined as well, so at least Illinois may be getting back some patrons who had crossed the border to gamble with Hoosiers.

Downstate casinos have suffered too. The Metropolis riverboat was down by double digits in fiscal 2013 (10.7 percent), after a new casino opened in Cape Girardeau, Mo., in 2012. Missouri opened St. Louis-area casinos in 2007 and 2010, leaving East St. Louis down 30 percent over the last five years and Alton down 37.1 percent over the same period. East Peoria, relatively unscathed, was down 3.6 percent in fiscal 2013.

Even so, thanks to Des Plaines, statewide casino receipts were up 18 percent this past year, compared to two years ago. So that should be great for schools, which get most of the riverboat tax revenues, right? Wrong. The riverboat contribution to schools grew only 4.9 percent in fiscal 2012 and 1.4 percent in fiscal 2013. The reason for such a paltry return to the state is that Illinois has a graduated income tax for casinos. Big healthy casinos pay the state at a higher rate than weakened, shrinking casinos. Most Illinois casinos fall into the latter category, now that their arms and legs have been bitten off. So they pay a lower tax rate on less total receipts, depriving schoolchildren.

If old casinos have it bad, racetracks are faring worse with the proliferation of gambling opportunities. The amount gambled at racetracks in calendar year 2012 was the lowest in the last 30 years of Illinois racing. So naturally the racetracks are wanting some relief in the form of slot machines, like they have at two big racetracks in Indiana and three in Iowa. Slots at tracks, included in the legislation now before the General Assembly, would not only bring money to the machines, proponents say; they would also increase attendance at the tracks so more people would bet on the horses. The trouble is that casinos at the Chicago-area Arlington and Maywood racetracks would both be only about 11 miles away from the new Des Plaines casino. That facility fears cannibals for good reason – it takes one to know one.

With receipts lagging, it’s only natural for casino operators to lobby for lower taxes on their takes. In 2004 the maximum tax rate on riverboats was 70 percent, but the casinos persuaded legislators to lower the maximum to 50 percent (minimum 15 percent), where it remains, still one of the highest riverboat taxing structures in the nation. But the latest gambling expansion proposals call for lowering the tax rates, “to make the Illinois casino market a more desirable place for owners to invest gaming marketing dollars.” More marketing would lead to higher attendance and more gaming receipts, the argument goes. The tax decreases proposed in the current gaming expansion legislation would cost the state of Illinois about $400 million. It would take a whole lot more gamblers to make that up.

What if huge crowds don’t show up at the proposed new casinos? “The potential exists,” says COGFA, “that, combined with lower tax rates and the cannibalization that will likely take place, the state could have a large expansion of gambling, but yet have little to no new tax revenues to show for it.” Until Illinois can do something about its cannibalism problem, the state will be better off to do nothing about expanding casino gambling, concentrating instead on protecting the casinos it already has.

James Krohe Jr.’s column, which usually appears in this space, will be back next week. He is off finishing a book. Contact Fletcher Farrar at [email protected].

Cannibalism in Illinois

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!