His bronze sculptures, monuments, and paintings tell of deep sorrow: the scars of slavery, the sacrifice of immigration, the quiet suffering of women.

His art also speaks of hope: the eloquent words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the restless spirit of pioneer Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, the creative rebirth of the Harlem Renaissance.

With metal and paint, Preston Jackson reveals our history.

From his most recent installation, Fresh from Julieanne’s Garden, a series of 33 bronze sculptures depicting women during slavery, to the large-scale sculpture “Travels of My Seven Sisters,” a representation of immigration, Jackson captures the stories of his culture and others’ with clarity.

As a fearless artist, and one of the state’s most renowned sculptors, Jackson has the freedom to explore prickly subjects such as racism, sexism, and immigration — and he gladly obliges.

Preston Jackson gets people excited, and that’s exactly what Springfield’s arts establishment is banking on.

For the first time, four of capital city’s leading art venues — the Illinois State Museum, the University of Illinois at Springfield Visual Arts Gallery, the Prairie Art Alliance’s H.D. Smith Gallery, and the Springfield Art Association — are joining forces to share a single artist’s vision.

The exhibition, titled Bearing Witness: The Art of Preston Jackson, opens Saturday and runs through October.

It’s sure to get Springfield talking.

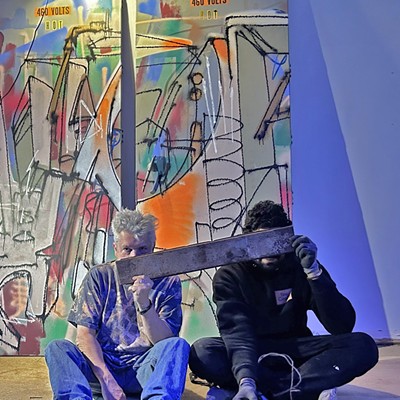

Three weeks to go before the opening of his Springfield show, and Jackson is in town to drop off some work. Having just finished painting the wheels of an outdoor sculpture that’s been moved to the UIS quadrangle, he’s taking a much-needed break to talk about his work.

Sitting against an empty wall in a Springfield Art Association gallery, the quiet, unassuming man with paint-spattered hands and a khaki ball cap with the bill turned backward doesn’t look much like a provocateur.

Looks are deceiving when it comes to this self-described outsider.

Jackson’s talent and his penchant for gritty subject matter make his work recognizable around the country, but not everyone takes note. Chicago Sun-Times critic Kevin Nance describes Jackson as a “major, though ludicrously underappreciated, master artist.”

Jackson considers it their problem, not his, and he’s learned to revel in the creative freedom that living outside the spotlight affords him.

“My subject is socially loaded, and I feel that I’m an artist that’s not afraid. I have no one to answer to. I don’t belong to the mainstream art attitude you see in art magazines,” Jackson says.

The 63-year-old artist, a native of Decatur, spends much of his time in transition. During the summer, he lives in Peoria, teaching art, jazz guitar, and tai chi at the Checkered Raven Galleries, home of the Contemporary Art Center of Peoria, a nonprofit center he founded 11 years ago. In the fall, he heads to Chicago, where he teaches sculpture at the School of the Art Institute. Whenever he’s not doing community work or teaching, Jackson is creating paintings, bronze castings, and large-scale monuments that find homes around the country. His Illinois works include a 9-foot-tall bronze of former Sun-Times columnist Irv Kupcinet at the corner of Wabash Avenue and Wacker Drive in the Windy City and a bust of Dr. King in Danville among a long list of others. He’s working on a small casting of the Haymarket riot and is completing a sculpture of comedian Richard Pryor, which will be installed at Peoria’s riverfront regional museum.

Fresh from Julieanne’s Garden depicts a series of African-American women during the late 19th century in such works as “Big Lou,” “Azalea,” “Corrine Nitel,” and “Guardian Sacrifice.” Some of the bronze castings have a primitive quality; Jackson says the style is reminiscent of traditional African art. Other pieces from the group are chillingly realistic. “Hog Killin’ Time” depicts Clara with an axe extended above her head and a hacked hog laid out on a table while a slave owner slinks away.

The visual images are arresting and often heartrending stories of courage in the face of hardship.

Jackson wanted the women’s stories to extend further than the visual images allowed, so he wrote them, posting the tales as part of his art and, in so doing, giving the women their own voices. Passed down from his family and stories he’s heard from people he’s met over the years, the tales tell of strength and restraint, violence and quiet bravery. Many of the castings are real people, real names, and real situations. Some of it is fiction, but the history is true.

“All of the things I’ve written, all of them have a basis of reality, a truth, and these are possible real incidents that happen, and most of them are; they always pose a question, Jackson says: “Who are we as human beings to deal with such dastardly activities like this? It’s a teaching process.”

Tragedy marks much of Jackson’s work, a reminder of the past and the strength of its ghosts, but the artist also deals in triumphs, evident in celebratory pieces such as Bronzeville to Harlem. He began building the love letter to Harlem Renaissance-period neighborhoods eight years ago. The sprawling work of painted steel and cast bronze is studded with 30 buildings and about 300 residents and automobiles. Jackson chronicles the heyday of jazz, literature, and art in the 1920s and ’30s, in the process uncovering a love for writing he never knew he had.

“The stories became funny and they became sad; they became ‘Wow, this is powerful stuff I’m telling to myself,’ so I began to write these things down and read them back,” Jackson says. “I discovered writing for the first time.”

Jackson doesn’t shy away from change, and when he grew tired of working with Bronzeville to Harlem five years ago, he put it aside. The artist’s productive nature allows him to delve into different styles and mediums. Painting gives him a break from the physical exertion of working with hot bronze and steel. His style on canvas tends be abstract representation, but during his graduate work at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, his outlook was quite different.

“When I was a graduate student, I chose to be an abstract-expressionist type of artist; I didn’t believe that representational art was necessary to express myself. Since then I’ve done a 180,” Jackson says. “I’m all the way back to the fact that certain cultures, mainly my own, and Haitian artists and Oceanic people, even Eskimos, the figure is very important, the figures are very representational — it gets rid of all the pretension.”

Jackson continues to explore the past and the strong cultures of our society. “I see a common thread that runs through all of humanity, cultures, and that’s what I’m centering my attention on,” Jackson says. He’s curious about the 1940s “zoot-suit riots” in California during which Mexican-Americans were brutalized, as well as the men who “risked their lives to go down in caves” mining in Appalachia. Jackson’s considered revisiting the people living in Bronzeville to Harlem, perhaps doing large-scale figures because of the elaborate nature of the clothing.

“I am experimenting with more diversity in my work, not only the costumes but people,” Jackson says, “people who don’t look like me, and they have a very strong history here, so I’m sort of branching out.”

Plans for a Springfield exhibit of Jackson’s work took shape several years ago as part of a freewheeling discussion about the need for local arts groups to work together.

Mike Miller, chairman of the visual-art department at UIS, and Bob Sill, assistant director of art at the Illinois State Museum, got the ball rolling; they were soon joined by Patrick Shavloske, then the director of the Prairie Art Alliance, and Erika Fitzgerald, former head of Springfield Art Association.

“Out of those first introductory meetings, it came up pretty quickly that Preston Jackson was somebody we really ought to think about doing,” Sill says.

Jackson showed work at Springfield’s Gallery 33 in 1999, but, with little attention paid, the exhibit went largely unnoticed. A few folks in town, such as Sill and Miller, had been aware of the sculptor’s work for some time.

“Preston had just started making the Julieanne’s Garden pieces, and I was really sort of blown away by those pieces,” Sill says.

“We just thought, ‘He’s from Decatur, and his story is great,’ ” Miller says. “We gave him a call just to feel him out, and he was interested.”

Soon after the project found wings, though, job changes grounded the citywide exhibition. Fitzgerald took a job in Chicago and Shavloske relocated to Florida, leaving the project at a standstill for a year while their successors — Angie Dunfee and Gayle Norton — settled in.

The next challenge was getting multiple gallery spaces at the same time. The Illinois State Museum plans its exhibits two years in advance, and finding a block of time the four active galleries had in common was the equivalent of solving a Rubik’s Cube.

Dividing Jackson’s large body of work between the four galleries wasn’t as difficult. Prairie Art Alliance received the 80-foot neighborhood Bronzeville to Harlem to coincide with the Route 66 Festival. The outdoor bronze-and-steel “Travels of My Seven Sisters” found a home on the grass in the center of the UIS campus. The large sculpture “The Dark Freighter” and 23 castings comprised by Fresh from Julieanne’s Garden are displayed at ISM including five brand-new pieces Jackson brought in the week the exhibition was installed. The remaining pieces will be exhibited at the UIS Visual Arts Gallery. The Springfield Art Association’s high ceilings were a perfect fit with Jackson’s paintings and welded pieces.

“It was kind of easy, because there are four bodies of work with Preston,” Dunfee says. “After we started looking at things, it started to sift itself out.”

Shortly after the original foundation was laid and schedules were matched, community members began building on the idea.

Mayor Tim Davlin threw City Hall’s support behind the effort, and an advisory committee of power players in the African-American community was quickly formed. Headed by Rudy Davenport, former head of the Springfield chapter of the NAACP, the group includes entrepreneur Mike Pittman; Ald. Frank McNeil; Chris Miller, UIS vice chancellor of student affairs; and Dr. Wes McNeese, president of the Springfield Ministerial Alliance. The group’s primary mission was to spread the word.

“I think Rudy [Davenport] said it well: ‘This is an artist of national representation, and we want to welcome him to town in a way that befits his stature,’ ” Miller says.

The energy surrounding the nationally recognized artist’s Springfield endeavor is infectious. The art community has finally rallied together, along with inhabitants of the city — a testament to Jackson’s universal appeal.

“His work is timeless. I think Preston has a way of speaking across cultural lines. He’s exploring the African-American experience from slave ships to the great migration,” Dunfee says. “He’s pretty courageous. His work is beautiful, and I think it’s accessible to everyone.”

The progressive opening for Bearing Witness: The Art of Preston Jackson begins at 4 p.m. Saturday, Sept. 9, with a reception at UIS and other events at the Springfield Art Association, 700 N. Fourth St.; the Prairie Art Alliance, 420 S. Sixth St.; and the Illinois State Museum, 502 S. Spring St. For additional details, see our Calendar listings. The exhibition ends Oct. 28.

Contact Marissa Monson at [email protected].