The great debate

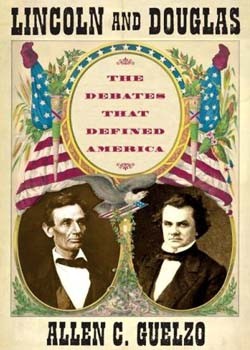

New look at Lincoln-Douglas contest answers longstanding questions

Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America

By Allen C. Guelzo, Simon & Schuster, 2008, 416 pages, $26

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

Untitled Document

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates are like the Magna Carta

or the Gadsden Purchase: You kind of know that they’re important and

maybe even have a rough notion of what they’re about. So why read

Allen C. Guelzo’s new Lincoln and

Douglas: The Debates That Defined America?

The prairies were a-fired up in 1858. Stephen

Douglas, Illinois senator and moral narcoleptic, tried his best to settle

the slavery issue, declaiming the doctrine of popular sovereignty. Folks

settling in new territories could vote up or down on whether those

territories would be free or slave. At the same time, the Dred Scott Supreme Court

decision, declaring that slaves were property and nothing more, heavily

suggested that Big Slavery would never be denied.

The book title tells you what’s going on.

Lincoln’s view of an America shaped by the Declaration of

Independence’s principle of natural human equality was the

“definition” that ultimately won.

Lincoln in Springfield in the early 1850s was like a discarded newspaper. Unsuccessful in politics, he’d been “retired” back to the law business. His Whig Party floundered, and he was a political man without a country. At the time of the debates, Douglas was the brilliant star of the Democratic Party and a likely future president. He had all the advantages — and if this all took place today Douglas would probably never have to publicly defend his manhood by debating Lincoln. The debates pulled Lincoln up and pushed Douglas down into a political (and physical) death spiral.

Guelzo clears up some smoky myths that swirl around the debates: the Ottawa Forgery, the Freeport Doctrine, Lincoln’s supposed North-South flip-flopping, and, best of all, a straight-up study of Lincoln’s Charleston speech. Activist scholars love to jump on Lincoln, calling him racist for his remarks in Charleston saying that a “physical difference” kept blacks and whites from social and civil equality. Guelzo terms the remarks “callous” and calls them an “exercise in racist pandering.” If someone has told you that Lincoln was a racist, kindly pick up Guelzo’s book and leaf through the Library of America’s Lincoln volumes. Read his speeches, read his letters; you’ll see that it’s not true.

Guelzo explains the political background to the debates — background that is every bit as interesting as the actual debates. We find the Illinois of the time a turbulent sea of political passion and intrigue, a grand stage for deep national issues. I’m happy to see him charting out the whole fall ’58 campaign, instead of merely discussing the seven debates, and then going on to note how the Lincoln-Douglas battle over ideals continued up until 1860. There’s a good movie in all of this. There have been other studies of the debates — chief among them is Harry Jaffa’s Crisis of the House Divided, but David Zarefsky’s work also stands out — but Guelzo’s broad view of debate politicking is a welcome addition to this area, as will be the debate transcripts now being worked on in the Knox College Lincoln center by Rodney Davis and Douglas Wilson.

The bottom line: This book is an extremely readable, enjoyable account of the great political battle between two rivals, each offering a distinct vision of what America should be, and how the debates doomed Douglas’ political career and catapulted Lincoln to national attention. This year is the debate sesquicentennial, and the Looking for Lincoln project has helped put together several debate-related events in the debate communities (Ottawa, Freeport, Alton, Quincy, Galesburg, Charleston, and Jonesboro), as well as Bement and Springfield. In fact, Guelzo will be in Springfield in June to discuss the Great Debates of 1858.

Todd Volker, who lives in Ottawa, attended Knox College in Galesburg and once met a woman who knew a man who met Lincoln.

Lincoln in Springfield in the early 1850s was like a discarded newspaper. Unsuccessful in politics, he’d been “retired” back to the law business. His Whig Party floundered, and he was a political man without a country. At the time of the debates, Douglas was the brilliant star of the Democratic Party and a likely future president. He had all the advantages — and if this all took place today Douglas would probably never have to publicly defend his manhood by debating Lincoln. The debates pulled Lincoln up and pushed Douglas down into a political (and physical) death spiral.

Guelzo clears up some smoky myths that swirl around the debates: the Ottawa Forgery, the Freeport Doctrine, Lincoln’s supposed North-South flip-flopping, and, best of all, a straight-up study of Lincoln’s Charleston speech. Activist scholars love to jump on Lincoln, calling him racist for his remarks in Charleston saying that a “physical difference” kept blacks and whites from social and civil equality. Guelzo terms the remarks “callous” and calls them an “exercise in racist pandering.” If someone has told you that Lincoln was a racist, kindly pick up Guelzo’s book and leaf through the Library of America’s Lincoln volumes. Read his speeches, read his letters; you’ll see that it’s not true.

Guelzo explains the political background to the debates — background that is every bit as interesting as the actual debates. We find the Illinois of the time a turbulent sea of political passion and intrigue, a grand stage for deep national issues. I’m happy to see him charting out the whole fall ’58 campaign, instead of merely discussing the seven debates, and then going on to note how the Lincoln-Douglas battle over ideals continued up until 1860. There’s a good movie in all of this. There have been other studies of the debates — chief among them is Harry Jaffa’s Crisis of the House Divided, but David Zarefsky’s work also stands out — but Guelzo’s broad view of debate politicking is a welcome addition to this area, as will be the debate transcripts now being worked on in the Knox College Lincoln center by Rodney Davis and Douglas Wilson.

The bottom line: This book is an extremely readable, enjoyable account of the great political battle between two rivals, each offering a distinct vision of what America should be, and how the debates doomed Douglas’ political career and catapulted Lincoln to national attention. This year is the debate sesquicentennial, and the Looking for Lincoln project has helped put together several debate-related events in the debate communities (Ottawa, Freeport, Alton, Quincy, Galesburg, Charleston, and Jonesboro), as well as Bement and Springfield. In fact, Guelzo will be in Springfield in June to discuss the Great Debates of 1858.

Todd Volker, who lives in Ottawa, attended Knox College in Galesburg and once met a woman who knew a man who met Lincoln.

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!