The duelist

Future governor became famous for tangling with Jeff Davis

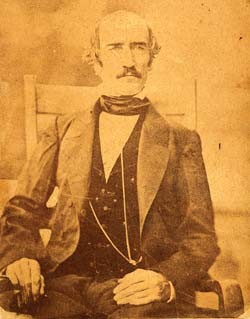

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

William H. Bissell became governor in 1857 and died three years later.

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

Untitled Document

To duel or not to duel — that was the question

Illinois congressman and Mexican War veteran William H. Bissell faced in

1850. He was challenged by Jefferson Davis, the future president of the

Confederate States of America. Bissell’s reply made him a legend in

the state and helped propel him to the governor’s seat.

Bissell was a Belleville physician and attorney who

had longed to serve in the military, according to the April 1994 Illinois History magazine.

When the Mexican War broke out, he enlisted and commanded the 2nd Illinois

Volunteer Regiment, which helped defeat Mexican troops at the extended

Battle of Buena Vista.

After the war, Bissell was elected to Congress in

1848 and re-elected in 1850. That year, Virginia’s James Seddon waxed

eloquent on the floor of Congress about Southern troops’ bravery at

Buena Vista, claiming that they “snatch[ed] from the very jaws of

death rescue and victory.”

Not exactly, according to Bissell, who kept his mouth shut until a Mississippi senator spouted off a month later about Southerners’ attributes. An article by Donald Tingley in the July 1956 Mid-America magazine says that Bissell rose and stated that the Southern regiment at Buena Vista was “not within a mile and a half of the scene of action” and that regiments from Kentucky and Illinois had saved the day. That did it. Davis, a U.S. senator from Mississippi by then, had commanded the Southern troops in question at Buena Vista and was proud of it, according to William J. Cooper’s book Jefferson Davis: American (2001). After writing Bissell to verify his comments, Davis challenged him to a duel.

Bissell accepted, and he and Davis chose “seconds,” or liaisons, to negotiate the duel’s conditions. The Springfield papers buzzed with tidbits about Bissell’s speech and the duel. The Feb. 27, 1850, Springfield Daily Register said that Bissell and Davis were “good shots, and both may be killed. Strong efforts are making to reconcile the parties.”

Subsequent Springfield articles lauded Bissell for standing up for Illinoisans’ bravery during the war and called him “the Gallant Bissell.”

Thirty-five years later, Dr. John Snyder, an amateur historian from Virginia, Ill., wrote Davis, asking why the duel never took place. In a Nov. 5, 1885, response (now part of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library’s collection), Davis cited two reasons: “The proposed meeting [duel] become known wherefore warrants were issued & I had some difficulty in avoiding arrest,” he wrote. (Dueling was illegal.) Also, a mutual friend, Sen. James Shields of Illinois, intervened and worked out a compromise whereby, Davis wrote, Bissell would write to Davis that he “never meant to make any injurious reflection on my Regiment or on myself. “Neither Col. Bissell nor I desired to attract the notice of the public or to be recognized in the Character of Duellist . . . ” added Davis — ironically, seeing as how he was the instigator. “Though in different parts of the field of Buena Vista Col. Bissell and I had the bond of hard service and suffering in a common cause and I regret that others have not chosen to forget a subsequent disagreement or to bury it in the memory of the fraternal past as He and I did.”

Illinoisans didn’t forget it for a long time; in fact, Bissell’s supporters used the duel to help get him elected governor in 1856, according to Tingley’s article. Before the election, the Daily Illinois State Journal reprinted a flattering article from a Chicago paper furthering Bissell’s legend as a courageous hero. It said that certain Northerners, including revered leader Daniel Webster, doubted that Bissell had the “metal” to accept Davis’s duel challenge in 1850. So Webster asked to meet Bissell, to “look him in the eye.” The two “grasped hands heartily,” and Webster said to a colleague, “He will do.”

Clearly, backing your statesmen and standing up to a Southerner made you an Illinois hero then, good enough for governor — but there was one problem. Duellists couldn’t be governor. Oops. According to Tingley’s article, the state Constitution forbade anyone who had “fought a duel” or “sent or accepted a challenge to fight a duel” from becoming an elected or appointed official.

A Joliet paper challenged Bissell on this point, but, once again, Bissell didn’t back down. He became governor in 1857 and died three years later, at the age of 49. He’s buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery. An ironic side note: James Shields, the mutual friend of Bissell and Davis who negotiated the compromise to their duel, would go down in history for a near-duel of his own — with Abraham Lincoln in 1842.

Tara McClellan McAndrew is lifelong Springfield resident and freelance writer. Contact her at [email protected].

Not exactly, according to Bissell, who kept his mouth shut until a Mississippi senator spouted off a month later about Southerners’ attributes. An article by Donald Tingley in the July 1956 Mid-America magazine says that Bissell rose and stated that the Southern regiment at Buena Vista was “not within a mile and a half of the scene of action” and that regiments from Kentucky and Illinois had saved the day. That did it. Davis, a U.S. senator from Mississippi by then, had commanded the Southern troops in question at Buena Vista and was proud of it, according to William J. Cooper’s book Jefferson Davis: American (2001). After writing Bissell to verify his comments, Davis challenged him to a duel.

Bissell accepted, and he and Davis chose “seconds,” or liaisons, to negotiate the duel’s conditions. The Springfield papers buzzed with tidbits about Bissell’s speech and the duel. The Feb. 27, 1850, Springfield Daily Register said that Bissell and Davis were “good shots, and both may be killed. Strong efforts are making to reconcile the parties.”

Subsequent Springfield articles lauded Bissell for standing up for Illinoisans’ bravery during the war and called him “the Gallant Bissell.”

Thirty-five years later, Dr. John Snyder, an amateur historian from Virginia, Ill., wrote Davis, asking why the duel never took place. In a Nov. 5, 1885, response (now part of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library’s collection), Davis cited two reasons: “The proposed meeting [duel] become known wherefore warrants were issued & I had some difficulty in avoiding arrest,” he wrote. (Dueling was illegal.) Also, a mutual friend, Sen. James Shields of Illinois, intervened and worked out a compromise whereby, Davis wrote, Bissell would write to Davis that he “never meant to make any injurious reflection on my Regiment or on myself. “Neither Col. Bissell nor I desired to attract the notice of the public or to be recognized in the Character of Duellist . . . ” added Davis — ironically, seeing as how he was the instigator. “Though in different parts of the field of Buena Vista Col. Bissell and I had the bond of hard service and suffering in a common cause and I regret that others have not chosen to forget a subsequent disagreement or to bury it in the memory of the fraternal past as He and I did.”

Illinoisans didn’t forget it for a long time; in fact, Bissell’s supporters used the duel to help get him elected governor in 1856, according to Tingley’s article. Before the election, the Daily Illinois State Journal reprinted a flattering article from a Chicago paper furthering Bissell’s legend as a courageous hero. It said that certain Northerners, including revered leader Daniel Webster, doubted that Bissell had the “metal” to accept Davis’s duel challenge in 1850. So Webster asked to meet Bissell, to “look him in the eye.” The two “grasped hands heartily,” and Webster said to a colleague, “He will do.”

Clearly, backing your statesmen and standing up to a Southerner made you an Illinois hero then, good enough for governor — but there was one problem. Duellists couldn’t be governor. Oops. According to Tingley’s article, the state Constitution forbade anyone who had “fought a duel” or “sent or accepted a challenge to fight a duel” from becoming an elected or appointed official.

A Joliet paper challenged Bissell on this point, but, once again, Bissell didn’t back down. He became governor in 1857 and died three years later, at the age of 49. He’s buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery. An ironic side note: James Shields, the mutual friend of Bissell and Davis who negotiated the compromise to their duel, would go down in history for a near-duel of his own — with Abraham Lincoln in 1842.

Tara McClellan McAndrew is lifelong Springfield resident and freelance writer. Contact her at [email protected].

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!