In the late 1800s reformers in Illinois became concerned about child labor in manufacturing, especially in the state’s larger cities. They had good reason to be. In some shops young children worked long hours at dangerous jobs that left them deformed or ill. Others worked at safer jobs, but the never-ending workdays (14-plus hours in some cases) made them virtual slaves.

After learning this, the Illinois legislature sent members to investigate Chicago factories firsthand in 1893, according to Lynn Gordon‘s article “Women and the Anti-Child Labor Movement in Illinois, 1890-1920” (The Social Service Review, June 1977).

That same year lawmakers passed legislation to address the problem. It outlawed employing children under the age of 14, mandated eight-hour workdays for children and women, required children aged 14 to 16 to submit proof of their age to employers, and appointed a state factory inspector, Florence Kelley, to oversee statewide compliance inspections annually.

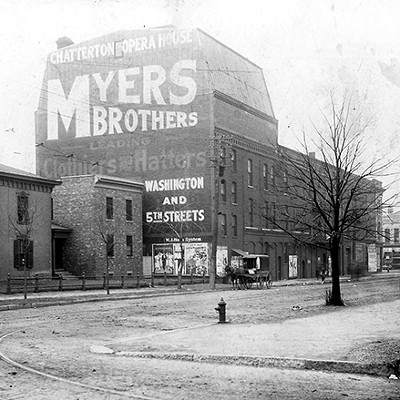

The first inspections in 1893 checked out small and large manufacturers in 16 towns, including Springfield, according to “The First Annual Report of the Factory Inspectors of Illinois,” printed in 1894 (at the state’s legally compliant Springfield printer, H. W. Rokker). While the worst scofflaws were in Chicago and Alton (at its glassworks), even smaller towns, including ours, had shops that employed children. All such businesses were noted in long lists in the report. Out of 17 Springfield businesses inspected in 1893, seven employed children under the age of 16.

That doesn’t necessarily mean they were breaking the law, however. It was legal to employ children aged 14 and older if they submitted proper verification of their age and if they submitted a doctor-approved health certificate, when necessary. Unfortunately, the report doesn’t say whether any of these businesses were violating the law by employing underage children or children without the proper credentials. Perhaps being placed on the list was intended as a warning that inspectors were keeping an eye on the business, but that’s strictly speculation.

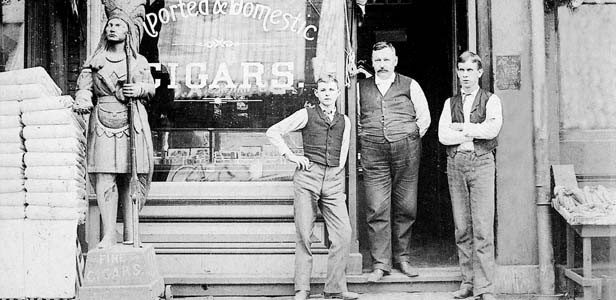

Throughout the state certain industries were cited as frequent abusers of child labor; one was sweat shops. The report told stories of sweat shops forcing employees to work 20 hours straight at times, until the workers fainted at their machines. The other frequent offender was cigar manufacturers.

Five of the seven Springfield businesses that used child labor were cigar and tobacco manufacturers. The report said the tobacco industry was one of the “more injurious” to children workers since it sometimes left them with “nicotine poisoning.”

One Springfield shop mentioned was Schoettker and Gehring, located at the northwest corner of Sixth and Monroe (where Congressman Aaron Schock’s office is now). Out of 15 workers, two were boys.

Yet “Springfield in 1892,” an Illinois State Journal supplement that described the town and many of its businesses, described Schoettker’s as “the greatest (cigar) manufacturer in the city.” The supplement said Schoettker’s had the country’s best ten-cent cigar, called the “Club Room,” and a terrific five-cent cigar called the “Red Label,” of which half a million sold in 1891.

Schoettker was the only cigar manufacturer in the supplement. That wouldn’t have been because it was the only one that joined the city’s highly lauded (according to the supplement) businessmen’s association, known as “the Citizens’ Improvement Association,” would it? The Journal supplement went on and on about the association, listed its members (including itself), and described its successes in bringing manufacturers to town. It cited many reasons that Springfield was a great place for them, including “rare” employee strikes “which have never embarrassed the managers of the industrial establishments of the city.”

The other Springfield cigar shops mentioned in the factory inspectors’ report sound like mom and pop establishments, with three to seven employees. Jacob Widner’s, at 212 S. Fifth (where Floyd’s Thirst Parlor is today), was the only place that employed more than one child; he had two.

The little shops weren’t the only places cited for child labor. One of Springfield’s larger factories was, too. It was the Springfield Woolen Mills at 422 S. Fourth St., on the east side of Fourth between Jackson Street and Capitol Avenue (today the parking lot across from Illinois National Bank). The Journal supplement called it “one of the oldest and most successful establishments of the kind in the West” (yes, its owner was a member of the city’s businessmen’s association, too.) Each year it used more than 100 employees, six sets of machinery, 27 broad looms, 2,500 spindles, and 500,000 pounds of wool to manufacture clothing that sold for $250,000, according to “Springfield in 1892.”

After the state factory inspectors found child labor violations throughout Illinois, they dismissed underage workers and took violators to court. All of the violators were from Chicago, many owned sweat shops or garment houses, one was located in a “cellar.”

In total, inspectors found 6,576 kids under the age of 16, not including the “hundreds” discharged because they were under 14, working in Illinois in 1893.

Just four years later, new legislation was passed to address the problem, but it was bittersweet. One provision required more types of businesses to follow child labor laws, but another loosened regulations for children’s working hours. It said children could work 10-hour days, instead of eight-hour days, and a total of 60 hours per week, instead of 40.

Contact Tara McAndrew at [email protected].

To learn more tidbits about Springfield history, visit the Facebook page for Tara’s book: go to www.Facebook.com and search for Stories of Springfield: Life in Lincoln’s Town.