Before graphic novels, there was Tintin

Hergé’s meticulously researched comic strip transcends age, language

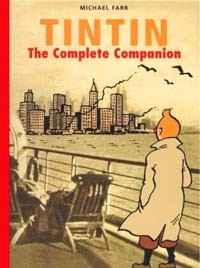

Tintin: The Complete Companion

By Michael Farr (Last Gasp, 2002, 200 pages)

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

Untitled Document

Billions of bilious blue blistering barnacles! In a

thundering typhoon! This is the 100th birthday of Belgian author/artist

Hergé. The complete Tintin isn’t the book you’ve all been waiting for,

though it should be.

Right now there’s a lot of hype about graphic novels, stories told pictorially, with balloon conversations. But these aren’t new — note the doors of the Duomo in Florence, the comic books of our childhood. In 1929, Hergé (Georges Remi’s reversed initials, French pronunciation) invented the boy reporter Tintin and his dog, Snowy. The popular newspaper strip found its way into books; the first translated into English was in the early ’40s. My kids were raised on Tintin: two, at 4 years, learned to read by the compelling dialogue and pictures. Not that these are kids’ books — they transcend age, and are found in 55 languages, including Hindi, Latin, and Esperanto. Hergé was a visionary anchored in fact: Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon preceded our moon landing by 20 years. His technology is amazingly accurate, for Hergé sought out scientific expertise for all his books, in addition to keeping voluminous archives of everything he might want to draw or use in plots. Most books deal with politics of the day (he anticipated the war with Japan), and often the villains, and heroes, are obvious. One can recognize also in his impeccable drawings exact landscapes, planes, trains, autos. (The kidnap car in The Seven Crystal Balls is a black salon, an Opel Olympia.) There’s danger aplenty; the hair-raising situations make Indiana Jones a piker. Humor ranges from subtle to slapstick. Tintin is the indispensable character, along with the irascible, voluble Captain Archibald Haddock, who doesn’t arrive till the ninth book, The Crab with the Golden Claws, but never leaves again. The detectives, Thomson and Thompson, continually mess up with blunders (to be precise, the blunders make a mess), while Professor Cuthbert Calculus — vague, wispy, hard of hearing, and eternally wandering off because of absorption in tangentials — is the Einstein who provides scientific know-how. The only woman is wealthy diva Bianca Castafiore, modeled on Maria Callas, who always steals the show.

This book weaves a history of Hergé and the years from World War I through 1983 with the writing and publishing of each book, not sparing Hergé’s illnesses occasioned by the physical and emotional demands of a daily strip plus life under Nazi occupation, where he was later unjustly accused of collaboration. A central fascination is the juxtaposition of drawings with their photographic sources. Today statues of Tintin and Snowy grace the center of Brussels, seven enameled copies of Hergé drawings are displayed alongside their photo prototypes on a Belgian quayside, while observances are going on world wide, including a huge show at Paris’ Pompidou. The book itself merits a stronger index and timeline. But these, and much other lore, can be found by Googling “Tintin.” Blistering barnacles, you bashi-bazooks, you freshwater swabs, ectoplasms, coelacanths (as the Captain, and my kids, swear frequently) — buy the Tintin companion, and then, of course, you’ll soon be into all 24 of these unique novels — every one in print. You can’t help yourself.

Jacqueline Jackson, books and poetry editor of Illinois Times, is professor emerita of English at the University of Illinois at Springfield.

Right now there’s a lot of hype about graphic novels, stories told pictorially, with balloon conversations. But these aren’t new — note the doors of the Duomo in Florence, the comic books of our childhood. In 1929, Hergé (Georges Remi’s reversed initials, French pronunciation) invented the boy reporter Tintin and his dog, Snowy. The popular newspaper strip found its way into books; the first translated into English was in the early ’40s. My kids were raised on Tintin: two, at 4 years, learned to read by the compelling dialogue and pictures. Not that these are kids’ books — they transcend age, and are found in 55 languages, including Hindi, Latin, and Esperanto. Hergé was a visionary anchored in fact: Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon preceded our moon landing by 20 years. His technology is amazingly accurate, for Hergé sought out scientific expertise for all his books, in addition to keeping voluminous archives of everything he might want to draw or use in plots. Most books deal with politics of the day (he anticipated the war with Japan), and often the villains, and heroes, are obvious. One can recognize also in his impeccable drawings exact landscapes, planes, trains, autos. (The kidnap car in The Seven Crystal Balls is a black salon, an Opel Olympia.) There’s danger aplenty; the hair-raising situations make Indiana Jones a piker. Humor ranges from subtle to slapstick. Tintin is the indispensable character, along with the irascible, voluble Captain Archibald Haddock, who doesn’t arrive till the ninth book, The Crab with the Golden Claws, but never leaves again. The detectives, Thomson and Thompson, continually mess up with blunders (to be precise, the blunders make a mess), while Professor Cuthbert Calculus — vague, wispy, hard of hearing, and eternally wandering off because of absorption in tangentials — is the Einstein who provides scientific know-how. The only woman is wealthy diva Bianca Castafiore, modeled on Maria Callas, who always steals the show.

This book weaves a history of Hergé and the years from World War I through 1983 with the writing and publishing of each book, not sparing Hergé’s illnesses occasioned by the physical and emotional demands of a daily strip plus life under Nazi occupation, where he was later unjustly accused of collaboration. A central fascination is the juxtaposition of drawings with their photographic sources. Today statues of Tintin and Snowy grace the center of Brussels, seven enameled copies of Hergé drawings are displayed alongside their photo prototypes on a Belgian quayside, while observances are going on world wide, including a huge show at Paris’ Pompidou. The book itself merits a stronger index and timeline. But these, and much other lore, can be found by Googling “Tintin.” Blistering barnacles, you bashi-bazooks, you freshwater swabs, ectoplasms, coelacanths (as the Captain, and my kids, swear frequently) — buy the Tintin companion, and then, of course, you’ll soon be into all 24 of these unique novels — every one in print. You can’t help yourself.

Jacqueline Jackson, books and poetry editor of Illinois Times, is professor emerita of English at the University of Illinois at Springfield.

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!