The human papillomavirus – or HPV – is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the world. There are more than 170 types of HPV, and about a dozen of them are linked to cancer.

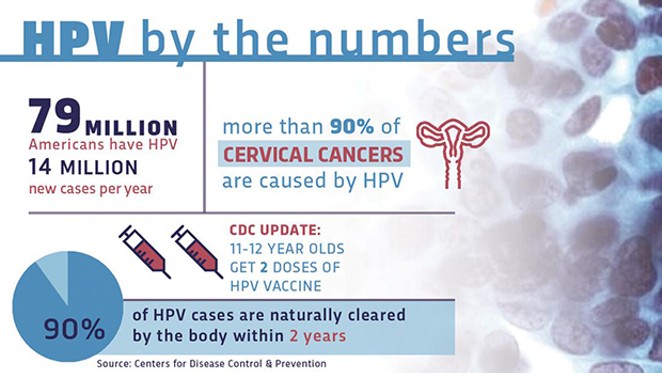

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than half of all sexually active people will contract one of the viruses during their lifetime.

Most infections go away on their own without causing serious problems. But in some people, an HPV infection persists and results in genital warts or precancerous lesions that increase the risk of cancer of the reproductive organs and of the mouth and throat. About 14 million Americans, including teens, are infected by HPV every year.

Now the good news: There’s a vaccine to prevent HPV. It’s been in use for more than a decade and is both safe and effective. It’s approved by the FDA and recommended for children ages 11-12, before they become exposed. It can be given beginning at the age of 9, up through age 26. Since its introduction in 2006, there’s been a 64 percent reduction in HPV infection among teenage girls.

SIU Medicine is one of many institutions striving to educate caregivers, colleagues and the public, in an effort to increase awareness about the intrinsic value of the HPV vaccine.

When the vaccine was first introduced, it was welcomed in the medical community as a new tool in the war against cancer. Unfortunately, misinformation about vaccines spread on the internet, magnified by some celebrities who connected it to autism, causing some parents to worry about the vaccine’s safety.

Careyana Brenham, M.D., associate professor of family medicine at SIU, encounters some of this hesitancy among parents. “The vaccine is still new enough that it makes some parents uncomfortable. They wonder if they should do it or not, and what they hear from other patients and in the media sometimes, no matter how unjust it is, plants doubts. All the published literature about vaccines and autism shows that there is no link between the two.”

Other parents may be uneasy about addressing their child’s eventual sexual activity, Brenham says. In fact, administering the vaccine to children before they reach puberty is optimal for two reasons. Children are still at home with their parents, making regular visits to their providers to keep current on the school’s vaccine requirements. And the timing helps the child establish a robust immune response should it ever be needed.

“As a mom, you want to do everything you can to keep your kids safe. My three oldest daughters have been vaccinated,” she says.

The vaccine is important for boys, too. Research has linked different HPVs to cancers affecting men.

For instance, approximately 70 percent of HPV-related head and neck cancers occur in men. It’s likely due to a combination of factors relating to differences in anatomy and immunology between men and women, says Dr. Arun Sharma, a head and neck surgical oncologist with Simmons Cancer Institute at SIU School of Medicine.

Usually, people are first exposed to it in their teens or twenties. “The HPV virus that causes head and neck cancer can go dormant for long periods,” says Dr. Sharma. “Most of the men getting an HPV-associated throat cancer are in their 40s, 50s and 60s – so, there is a timespan of decades between exposure and clinically evident cancer.” The HPV vaccine can block that hidden threat, once and for all.

Communication about the vaccine will be critical to its success. Gina Lathan, immunizations section chief at the Illinois Department of Public Health, says, “The challenge is to normalize the subject so that it gets greater traction with families. We want vaccines to be brought up when the children are young, when it can do the most good, and become part of the overall health plan: diet and exercise, safety in the neighborhoods, etc. We need to make sure it becomes a part of the conversation,” she said.

The HPV vaccines are driving cancer rates down. “It’s amazing,” Dr. Brenham says. “Imagine eliminating a type of cancer. I really believe we could see it in my lifetime.”

Steve Sandstrom is communications coordinator for the Office of Public Relations at SIU School of Medicine.

Educate and vaccinate

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!