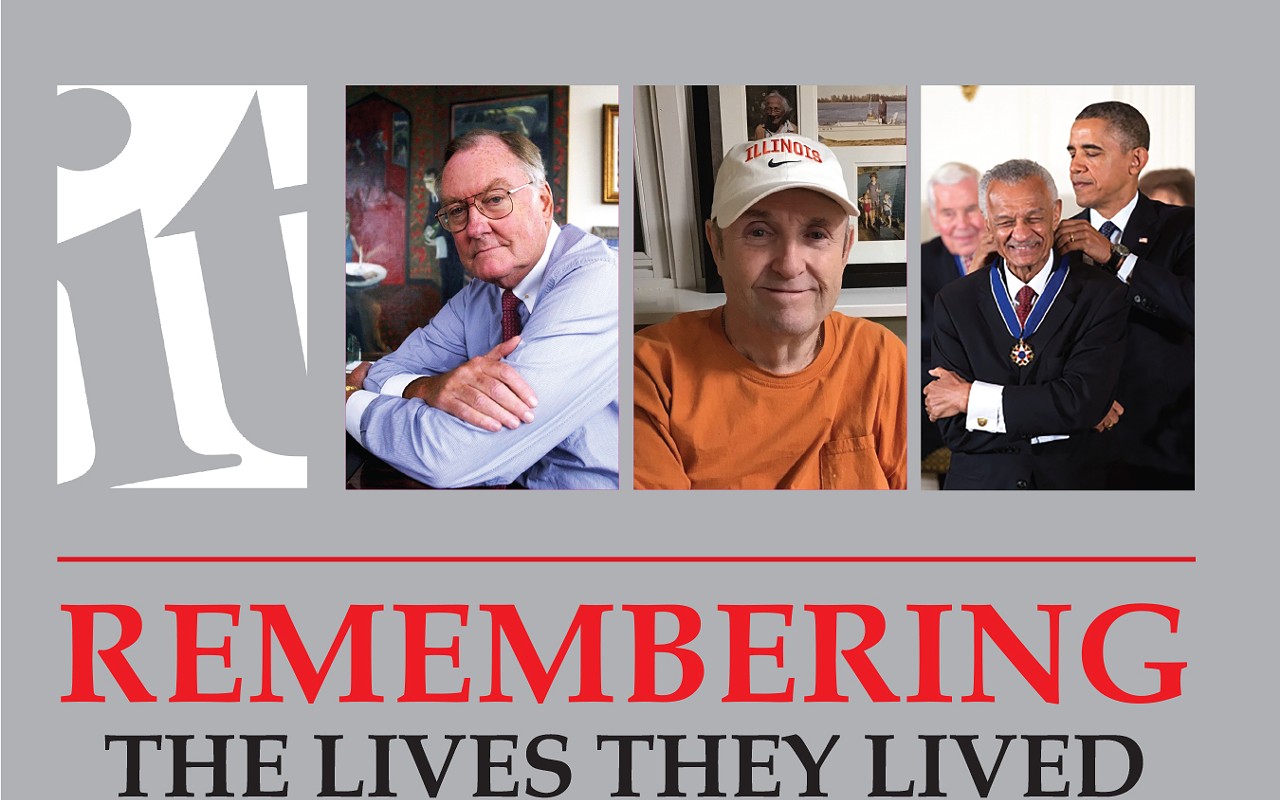

Big Jim

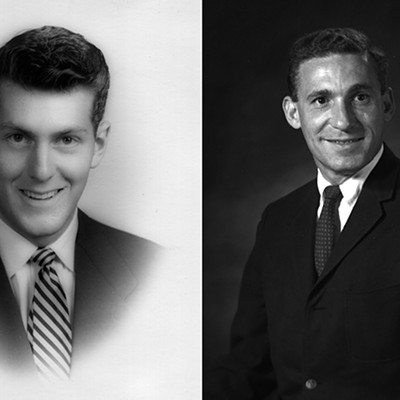

JAMES ROBERT THOMPSON May 8, 1936-Aug. 14, 2020

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

From his graduation in 1959 at Northwestern University School of Law until he died Aug. 14, 2020, at age 84, James Robert Thompson made an indelible imprint on Illinois history.

Over those six decades, he lived life large, most of it in public view from one end of the state to the other. Thus, his personal label: Big Jim Thompson.

The media that seemingly followed his every footstep summarized the obvious highlights: Prosecution and conviction of former governor Otto Kerner; 14 years as governor, more than any other in Illinois history. Those, enhanced by his dominating six-foot, six-inch frame and a personal relentless publicity machine, are notable. But there is more.

Thompson’s story is best condensed in three epochs: 1. Intellectual growth and high-profile prosecutorial career, 1959-1976 2. Four terms as governor, 1977-1991 3. Law firm powerhouse, 1991 to retirement

Thompson joined the Northwestern law school faculty after graduation. Working with his mentor, Professor Fred Inbau, he coauthored law books and fought public legal battles. On April 29, 1964, Thompson argued the case of Escobedo v. Illinois before the U. S. Supreme Court. He lost a 5-4 decision, but fired the first shot in a revolution that altered all practices in questioning suspects and obtaining confessions. Inbau called it “the finest oral argument.” Thompson was 28 years old.

Seven years later, after legal victories and losses and one year as an administrator in the state attorney general’s office, Thompson was named U. S. attorney, with offices in Chicago. He held that position from 1971 to 1975, during which he was in media spotlights continually.

Most noteworthy during this period – and controversial for the rest of his life – was the prosecution and conviction of federal appeals court judge, and former governor, Otto Kerner. To this day, many who remember Kerner fondly question the evidence, tactics and politics of the case.

Overshadowed by the Kerner trial is Thompson’s “crusade to clean up Chicago.” Over the course of numerous trials, the U. S. attorney’s office tried and convicted several close associates of Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley for corrupt practices.

Those accomplishments prepared Thompson for the second epoch.

As a Republican he was elected governor in 1976 by a large margin. A flamboyant campaign style served to energize his followers. Initially, he was a babe in the political wilderness, but he matured rapidly.

For most of his 14 years in office, Democrats controlled the legislature. That rarely crippled Thompson as he introduced an avalanche of policy ideas, many requiring lavish expenditures. One political observer described his governing style: “He ran as a Republican but often governed as a Democrat.”

After winning a second term by a large margin of votes in 1978, it appeared Thompson would never have a close contest. That picture changed in 1982 when former U. S. senator Adlai E. Stevenson III battled him to the wire, Thompson winning by 5,074 votes out of 3.6 million cast. Stevenson tried again in 1986 and lost.

Thompson had his failures, just like most governors, but few blunders stained his record. One victory that still resonates with citizens, especially those in Chicago, occurred in 1988. Owners of the White Sox baseball team threatened to leave for Florida if the legislature failed to approve financing for a new ball park. With the bill to save the White Sox hanging by a thread in the final hours of the legislative session, Thompson and associates traveled to Springfield and lobbied the measure to passage. He saved the White Sox for Chicago.

Thompson did not seek a fifth term. In January 1991 he started the third epoch.

During Thompson’s first campaign for governor he had no job, and the Chicago law firm of Winston and Strawn paid him a salary of $50,000. In 1991, Thompson entertained offers for his services. Winston and Strawn had the inside track, and he joined the firm. Two years later he was named chairman, a position he held for 13 years. He built the firm into a national and international legal giant, and earned a personal fortune.

Rather than hide behind a desk, he continued to lobby the legislature for high-profile clients while maintaining visibility in Chicago legal and social circles. His most prestigious performance at a national level occurred when he was named to the 9-11 Commission, which revealed the failings of many government agencies at the time of crisis. He considered that responsibility one of the most important in his life. Although rumored as a possibility for U. S. president or vice president, those opportunities never materialized.

Was he loved? Certainly, by his wife, Jayne, and daughter, Samantha.

Was he respected? Yes, by all who benefited from his power and patronage.

Was he benevolent? Ask convicted former governor George Ryan, who Thompson defended pro bono.

Could he govern? He did what was necessary to win. His life in a word: Memorable.

Robert E. Hartley is the author of Big Jim Thompson of Illinois. His most recent book, Power, Purpose and Prison: Stories about Former Illinois Governors, features Thompson.

Over those six decades, he lived life large, most of it in public view from one end of the state to the other. Thus, his personal label: Big Jim Thompson.

The media that seemingly followed his every footstep summarized the obvious highlights: Prosecution and conviction of former governor Otto Kerner; 14 years as governor, more than any other in Illinois history. Those, enhanced by his dominating six-foot, six-inch frame and a personal relentless publicity machine, are notable. But there is more.

Thompson’s story is best condensed in three epochs: 1. Intellectual growth and high-profile prosecutorial career, 1959-1976 2. Four terms as governor, 1977-1991 3. Law firm powerhouse, 1991 to retirement

Thompson joined the Northwestern law school faculty after graduation. Working with his mentor, Professor Fred Inbau, he coauthored law books and fought public legal battles. On April 29, 1964, Thompson argued the case of Escobedo v. Illinois before the U. S. Supreme Court. He lost a 5-4 decision, but fired the first shot in a revolution that altered all practices in questioning suspects and obtaining confessions. Inbau called it “the finest oral argument.” Thompson was 28 years old.

Seven years later, after legal victories and losses and one year as an administrator in the state attorney general’s office, Thompson was named U. S. attorney, with offices in Chicago. He held that position from 1971 to 1975, during which he was in media spotlights continually.

Most noteworthy during this period – and controversial for the rest of his life – was the prosecution and conviction of federal appeals court judge, and former governor, Otto Kerner. To this day, many who remember Kerner fondly question the evidence, tactics and politics of the case.

Overshadowed by the Kerner trial is Thompson’s “crusade to clean up Chicago.” Over the course of numerous trials, the U. S. attorney’s office tried and convicted several close associates of Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley for corrupt practices.

Those accomplishments prepared Thompson for the second epoch.

As a Republican he was elected governor in 1976 by a large margin. A flamboyant campaign style served to energize his followers. Initially, he was a babe in the political wilderness, but he matured rapidly.

For most of his 14 years in office, Democrats controlled the legislature. That rarely crippled Thompson as he introduced an avalanche of policy ideas, many requiring lavish expenditures. One political observer described his governing style: “He ran as a Republican but often governed as a Democrat.”

After winning a second term by a large margin of votes in 1978, it appeared Thompson would never have a close contest. That picture changed in 1982 when former U. S. senator Adlai E. Stevenson III battled him to the wire, Thompson winning by 5,074 votes out of 3.6 million cast. Stevenson tried again in 1986 and lost.

Thompson had his failures, just like most governors, but few blunders stained his record. One victory that still resonates with citizens, especially those in Chicago, occurred in 1988. Owners of the White Sox baseball team threatened to leave for Florida if the legislature failed to approve financing for a new ball park. With the bill to save the White Sox hanging by a thread in the final hours of the legislative session, Thompson and associates traveled to Springfield and lobbied the measure to passage. He saved the White Sox for Chicago.

Thompson did not seek a fifth term. In January 1991 he started the third epoch.

During Thompson’s first campaign for governor he had no job, and the Chicago law firm of Winston and Strawn paid him a salary of $50,000. In 1991, Thompson entertained offers for his services. Winston and Strawn had the inside track, and he joined the firm. Two years later he was named chairman, a position he held for 13 years. He built the firm into a national and international legal giant, and earned a personal fortune.

Rather than hide behind a desk, he continued to lobby the legislature for high-profile clients while maintaining visibility in Chicago legal and social circles. His most prestigious performance at a national level occurred when he was named to the 9-11 Commission, which revealed the failings of many government agencies at the time of crisis. He considered that responsibility one of the most important in his life. Although rumored as a possibility for U. S. president or vice president, those opportunities never materialized.

Was he loved? Certainly, by his wife, Jayne, and daughter, Samantha.

Was he respected? Yes, by all who benefited from his power and patronage.

Was he benevolent? Ask convicted former governor George Ryan, who Thompson defended pro bono.

Could he govern? He did what was necessary to win. His life in a word: Memorable.

Robert E. Hartley is the author of Big Jim Thompson of Illinois. His most recent book, Power, Purpose and Prison: Stories about Former Illinois Governors, features Thompson.

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!