It doesn’t seem possible, but 60 years ago people survived without air conditioning. Not only did they survive, but they may have even enjoyed life more, since they actually went outside in summertime and talked to their neighbors. Today the only people without it are the poor and radical environmentalists doing their part to avert climate change catastrophe. One of the country’s worst generators of greenhouse gas, air conditioning now accounts for twice the energy consumption it did in the early 1990s.

Fortunately, there are some simple ways homeowners can reduce, if not eliminate, air conditioning even in our humid Midwestern climate. Renewable options like evaporative coolers and solar chimneys may make matters worse in the hottest part of Illinois summers by increasing the humidity in the house, according to Gary Hurley, operations coordinator for CWLP. But shading windows on the west side of the house to block the hot afternoon sun can be very effective, as well as shading east windows to prevent heating in the morning. Because the sun is too high in the sky in summer to shine in south windows, however, shading doesn’t do as much for them.

Exterior shading is much more effective than just closing an inside curtain because it prevents sunlight from heating the window and the airspace next to it. “The best thing you can do is shade from the outside before it ever hits the window,” says Bob Croteau, renewable energy instructor at Lincoln Land Community College. Trees are ideal for shading since they keep sun off the wall and roof as well, but let sunlight through in winter. Awnings or solar shade screens are other options for east and west windows. A solar screen is a fiberglass mesh that lets air through while shielding insects and up to 70 percent of sunlight.

For houses older than 20 years, Croteau recommends applying low-e films to west and east windows to block 50 percent of the sunlight. Newer windows already have low-e coatings incorporated in them. Low-e films have the advantage over window coverings of allowing some daylight in.

Promoting the natural ventilation in the house can supply a lot of cooling. At night when the air outside is cooler than inside, Hurley of CWLP says windows should be opened on opposite sides of the house in the direction of the prevailing wind, which in summer is usually from the south. By closing the windows on the other sides of the house, you can create a wind tunnel that draws in cool air. The open windows must be directly opposite each other with no walls impeding the flow. Absent the wind tunnel effect, a homeowner could put a fan in the window of an empty upstairs room to pull warm air out of the house.

In the 1970s, whole house fans became popular as a way to expel hot air from the house up through the attic, drawing cool air in below from outside the house. Hurley estimates they are installed in 8 to 10 percent of Springfield homes, including one just built on Lake Springfield. But they are best used on hot days in fall and spring, he says. In the heat of summer, the fans just pull hot, humid air into the house.

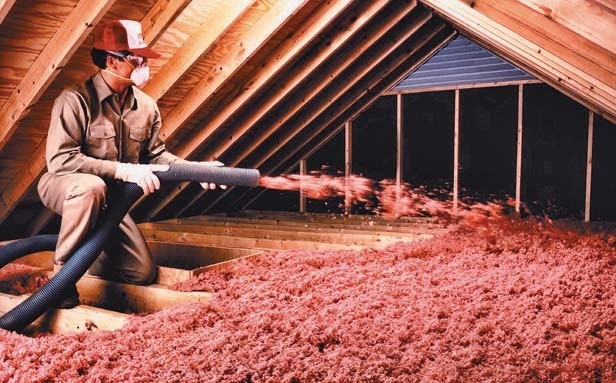

“You can actually fill the house with humidity using a whole house fan,” says Croteau. “If you do the calculations, it would actually be a lot cheaper to just add six more inches of insulation to your attic and eliminate the heat buildup that you’re otherwise trying to combat with the whole house fan.”

A solar-powered attic fan can be valuable in venting attic heat, Hurley says. Smaller than a whole house fan and covered by a solar panel, it operates on the electricity generated by solar cells to draw air out through vents made in the roof. “The more sun, the faster the fan runs,” notes Croteau. At $300 or more, one fan typically can vent up to 1,000 square feet. Croteau cautions that only houses that don’t have enough passive venting in the roof would get any benefit from a solar attic fan. A low-slope roof would be a good candidate for one because the air is not directed as quickly upward to vent as in a gabled roof.

But Croteau points out that a foot-thick layer of insulation in the attic can create such a barrier against the heat buildup in the roof that venting it quickly is not so critical. If your insulation is fiberglass, he suggests adding a layer of cellulose insulation on top to prevent heat radiating from the roof into the house through the fiberglass. Because cellulose is opaque to light, it stops radiant heat in its tracks.

Attic insulation retains cool air in the house as well. Hurley recommends at least 14 inches of insulation, in addition to sealing any air leaks in the house and closing storm windows in summer.

The best green solution Croteau has found for his own residence is to install solar panels on the roof that supply enough electricity on sunny days to run the air conditioner. Although the panels cost $8,000, he received a rebate of $3,000 from CWLP through its Solar Rewards program, as well as $3,400 from a federal tax credit and a state grant. “If you’re just coming at it from an economic angle, it’s not worth doing,” he says. “I did it because it was environmentally an important thing to do. I’m hoping my grandchildren will benefit from my contribution.”

Karen Fitzgerald, a writer in Pleasant Plains, can be contacted at [email protected]. Read her blog at http://springfieldskinny.wordpress.com/.