On Jan. 16, 1919, the United States had ratified the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, making it illegal to make, transport or sell alcoholic beverages in America as of 1920. The following Sunday, celebrations were held in churches throughout Springfield. Reverend E. F. Collier spoke in support of the Anti-Saloon League at the First United Brethren Church. “A Jubilee Over King Alcohol” was held at the Fifteenth Street Methodist Church. A sermon entitled “Who Put the Nation on the Water Wagon?” was delivered at the Kumler Methodist Episcopal Church. These churches and many others had been leaders in the city’s temperance movement, and now they believed their victory over “king alcohol” was at hand.

Springfield’s United States District Attorney, C. E. Knotts, was less jubilant and more pragmatic. “The bootlegger will be succeeded by the moonshiner,” he predicted, adding, “Nobody can make an intelligent guess as to what the outcome of laws will be.”

History has shown that the outcomes of Prohibition were overwhelmingly negative. Ultimately, the 18th Amendment led to billions of dollars of lost federal revenue, expanded organized crime, turned ordinarily law-abiding citizens into criminals and killed upwards of 10,000 people who drank denatured alcohol.

Yet a century ago, Americans looked forward to the dawning of a new, dry era with nothing but optimism. The majority of citizens at the time sincerely believed that alcohol was at the root of the nation’s social problems, and a prohibition on the sale of alcohol would make those problems go away.

The road to Prohibition was a long and bumpy one that stretched all the way back to the Mayflower, which was stocked with beer for the voyage. Europeans colonized America with much more liberal ideas about the consumption of alcohol than we have today. Alcohol was seen as a healthy alternative to often-polluted water supplies and was even taken as medicine. Beer and cider were served at mealtimes, even to children. Workmen and farmers took breaks to drink. Alcohol flowed at weddings, funerals and elections. In short, colonial and early Americans were a boozy lot.

During the 18th century, colonists preferred rum, which they imported from the Caribbean or distilled themselves from Caribbean molasses in one of 150 New England rum distilleries. American rum wasn’t good, but it was cheap, and consumed to such a degree that Benjamin Franklin came up with 228 synonyms for being drunk.

Rum fell out of favor during the American Revolution, when it was considered unpatriotic to drink a spirit brewed from a byproduct of British sugar plantations shipped to America on British vessels. Whiskey, on the other hand, was distilled from good old American-grown grain, and its popularity took off during the Revolution. After the war’s end, whiskey started to be produced in vast quantities. For farmers moving west, distillation of whiskey became a logical and lucrative use for extra grain that couldn’t be shipped to market.

Lots of whiskey being distilled meant lots of whiskey being consumed. By 1830, whiskey could be purchased for 25 cents a gallon (cheaper than coffee, tea or milk), and the average American consumed the equivalent of 90 bottles of standard 90-proof liquor per year, three times as much alcohol as is drunk today.

All that liquor consumption didn’t come without a social price. Habitual drunkenness became a serious issue in early America, and stories abounded of bright, promising youths whose fondness for the bottle caused their ultimate ruin, or families destroyed by drunk husbands. The very first person to be hanged in Springfield was Nathanial Van Noy, who had killed his wife while intoxicated on Aug. 27, 1826.

Enter the temperance movement. The first American temperance societies sprang up in the 1830s and 40s in response to the social problems spawned by excessive alcohol consumption. Steeped in the culture of the second great religious awakening, these temperance societies viewed intemperance as a sin, like slavery, that they hoped to eradicate by urging drinkers to voluntarily practice restraint. Their target was mainly the middle class, who responded enthusiastically to the cause of temperance. To this generation of “self-made men” in early America, sobriety went hand in hand with hard work and ambition as a ticket to upward mobility.

Though he never formally declared himself a temperance man, Abraham Lincoln flirted with the temperance movement and was not known to drink. In 1842, he gave an address to the Washingtonians, a temperance group founded by reformed alcoholics in Baltimore who strove to offer empathy and encouragement rather than judgment and shame to those trying to get sober. Lincoln approved of this approach, and urged temperance advocates to remember that “when the conduct of men is designed to be influenced, persuasion, kind, unassuming persuasion, should ever be adopted.”

Unfortunately, persuasion wasn’t getting the job done. By the 1850s, the temperance movement started pushing for the restriction of alcohol by statute. In 1851, Illinois passed a law banning the sale of alcohol in quantities less than a quart unless by specially licensed apothecaries, forbidding consumption where sold, and banning sale to anyone under age 18.

The same year, the state of Maine passed an even stricter law, banning the sale of all intoxicating liquors of any quantity, except for medicinal purposes. Almost immediately, temperance advocates in Illinois began agitating for a “Maine law” of their own. In December 1853, more than 240 delegates from 24 counties met in Chicago and organized the “Illinois Maine Law Alliance,” which lobbied vigorously for the next year and a half. But when a referendum for statewide prohibition finally went on the ballot in 1855, the measure was voted down, largely because it was unpopular in densely populated urban areas.

In Springfield, however, the local hard-line temperance men were able to muscle through a “Maine Law” city ordinance. Passed in May 1854, it prohibited the sale of spiritous, vinous and malt liquors within city limits, without regard to quantity. Many of the men behind this ordinance were Lincoln’s lawyer friends, including James C. Conkling, Stephen T. Logan and James Matheny. Lincoln’s brother-in-law’s brother, Benjamin Edwards, not only authored the ordinance, he also teamed up with the city attorney to see that it was rigidly enforced. “Life was made a burden to violators of the liquor ordinance that year,” the city attorney later recalled.

Springfield’s liquor ordinance lasted little over a year. By October of 1855, the Illinois State Register noted that it was little more than a “dead letter upon the statute book,” that business had been adversely affected and that drinking problems in the city were worse, not better. A week later, the ordinance was repealed by the vote of a special city election. The following year, the Maine state legislature repealed the original “Maine law.”

The strident activity of the temperance movement and its resulting pushback reflected the complex social divisions beginning to take shape in the United States at that time. Between 1840 and 1860, nearly 4 million foreign immigrants had entered the United States. Most of them were Irish and Germans who brought with them cultures steeped in the consumption of whiskey and beer, respectively. As swelling cities led to increasing poverty, crime and disease, those with a nativist bent blamed these social problems on immigrants, whom they stereotyped as inebriates. The temperance movement thus took on a dark, nativist undertone as the middle-class and native-born attempted to regulate the behaviors of the immigrant and working classes. Unsurprisingly, members of the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic Know-Nothing party were strong advocates of temperance.

The Know-Nothing party largely dissolved before the Civil War, as did Illinois’ first wave of anti-liquor legislation, but the temperance movement did not. It did, however, get pushed to the back burner as the nation’s attention and resources were consumed by war.

After the Civil War, an increasingly industrializing economy coupled with the availability of cheap western farmland ushered in a second wave of European immigration. Savvy European-American entrepreneurs such as Adolphus Busch, Frederick Miller and Frederick Pabst realized that these new immigrants would want beer, so they established and expanded breweries to meet the growing demand. Between 1850 and 1880 the amount of beer produced in America annually more than quadrupled, from 700 million gallons to more than 4 billion gallons each year.

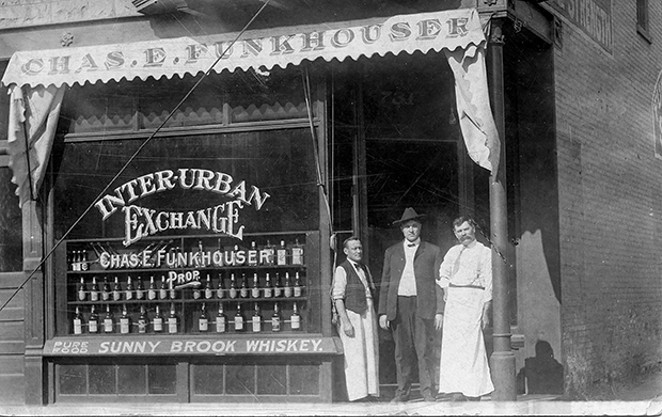

Most of that beer was consumed in another expanding feature of American culture: the saloon. Springfield had 32 saloons and restaurants in 1859. By 1890, it had over 120 saloons alone. More than just drinking establishments, saloons functioned as social clubs for working and ethnic communities. They were places to get letters translated and checks cashed and maybe find a job. They were places for factory workers and coal miners and office clerks to unwind after a day of difficult, monotonous or physically grueling labor.

They were also places to get drunk, and as the number of saloons in the country grew, so did the magnitude of alcohol-related social problems. The temperance movement, dormant during the Civil War, was revived in a big way during the 1870s. This time, however, women were leading the charge. Fueled by cultural assumptions they held moral and spiritual authority, women were increasingly participating in social reform movements. The question of temperance was seen as vital to women, since wives and children were often collateral victims of alcoholism, lacking social or legal recourse against husbands and fathers who drank up their paycheck or became abusive when drunk.

In 1874, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union was formed in Ohio. Soon after, a local temperance movement got underway in Springfield. Like the WCTU, the Springfield movement would operate by “prayer and entreaty with the saloon keepers to give up the traffle, and with the bibulous to give up their tippling habits,” according to the Illinois State Register.

To that end, in March 1874 a group of crusading women marched on several local saloons, dogged by a large and boisterous crowd of curious onlookers, on a mission to convince the proprietors to close their doors. At each saloon, they sang, prayed and urged patrons to sign pledges of total abstinence. In most places the proprietors told them politely but firmly that they saw no sin in drinking and weren’t about to give up their business operations.

James Rayburn, however, agreed to close his establishment at the corner of Fifth and Washington streets, destroy his stock of liquor, and take a temperance pledge if only the ladies would loan him $500 to start a new business. Money was quickly raised and, on March 28, a crowd of women descended on Rayburn’s saloon to break demijohns and take hatchets to barrels, while Reverend W. H. Reed shouted in the background about the danger posed to society by the “bloated Dutch” and “red-nosed Irish,” the “scum of the society of Europe.”

The success with Rayburn notwithstanding, the temperance crusaders didn’t have much luck closing saloons or pushing temperance using prayer and persuasion alone. In the 1890s, however, the W.C.T.U. gained a powerful new ally in the Anti-Saloon League. First organized in 1893, its mission was to promote legislation that would ban the sale of alcohol locally, and ultimately nationally through an amendment to the Constitution. To reach this aim, the Anti-Saloon League partnered with churches, business moguls and politicians of all stripes to conduct the most ruthlessly efficient grass-roots lobbying campaign in American history.

Fifty years earlier, Abraham Lincoln said “too much denunciation against dram sellers and dram drinkers” was “impolitic and unjust.” Is it any wonder that saloonkeepers and drinkers don’t listen to you, he pointed out, when they are told “they were the authors of all the vice and misery and crime in the land; that they were the manufacturers and material of all the thieves and robbers and murderers that infested the earth; that their houses were the workshops of the devil”?

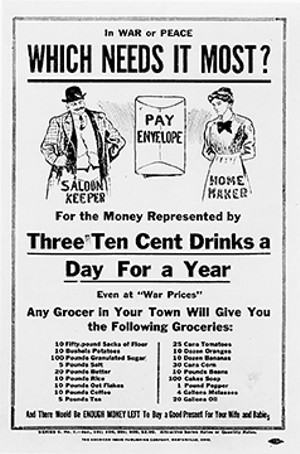

Once the Anti-Saloon League came on the national scene, however, denunciation against dram sellers became the name of the game. Vast amounts of propaganda were cranked out highlighting the evils wrought by saloons on society, mostly variations on the theme of broken homes, battered wives and starving or neglected children.

By the turn of the 20th century, drinking became a wedge issue that divided America every bit as sharply as partisan politics divides it today. The “wets” tended to be urban, ethnically diverse and often Catholic. Often they were immigrants, to whom drinking was a cherished part of their culture, or members of the working class, who found companionship and recreation in saloons. “Drys” tended to be rural, native-born and Protestant. They saw the very real problems creeping into an increasingly industrializing and urbanizing America and believed that alcohol was at the heart of them.

True to this generalization, the 21 rural townships in Sangamon County voted themselves dry as soon as legislation made this an option in 1908. Over the next eight years, five more townships went dry, until only Capital Township, whose boundaries align with those of Springfield, remained “wet.” Finally, in 1917, bolstered by women (who were allowed to vote in local elections), Springfield went “dry.”

On the national level, it took three major events to pave the way for the ratification of the 18th Amendment. The first was ratification of the 16th Amendment to the Constitution – implementation of a national income tax. Prior to this amendment’s ratification in 1913, more than half of the federal government’s revenue came from taxes on liquor sales. With a new stream of revenue provided by income taxes, a prohibition on the sale of alcohol became much more feasible.

The second was the success of the Anti-Saloon League and W.C.T.U. in overseeing the election of a two-thirds majority of “drys” in both houses of Congress, giving them enough votes to see a Prohibition amendment passed.

And the third was the outbreak of World War I, in which Germany was the main enemy. American temperance advocates used propaganda to demonize German brewers and link “dry” politics to patriotic support of the war.

Illinois became the 26th state to ratify the 18th Amendment on Jan. 14, 1919. In Springfield, a grand jubilee was held at the First Methodist Church to celebrate. Two days later, on Jan. 16, Nebraska became the 36th state to ratify, crossing the required threshold of three-fourths of the states. America had collectively decided that as of Jan. 17, 1920, it would be illegal to manufacture, sell or transport intoxicating liquors. History has shown that Prohibition ultimately did much more harm than good, but a century ago, all the people of Springfield felt was optimism now that “John Barleycorn” had been delivered a “knockout blow.”

Erika Holst is the curator of decorative arts and history at the Illinois State Museum.