A lot of people, I suppose, thought that George McGovern had died a long time ago when they heard in October that he had passed away. Some of them could even have put a date on his demise – election night 1972, when he lost his presidential campaign to the incumbent Richard Nixon in a laugher. The Democrat lost every state but Massachusetts, failing even to win his home state of South Dakota.

That last fact tells you more about South Dakota than it does about McGovern, as indeed does the national result. I am among the many who prefer to remember the senator not for how he did that year but for what he tried to do. His campaign platform was breathtakingly ambitious, and daftly naïve. He promised to slash war spending and end the war in Vietnam, to give amnesty to draft-evaders, universal health care to the sick, a job for every American who could work and an income above the poverty line for every household. He was not ahead of the times on issues but behind – about 60 years behind in fact; the last time most of those ideas commanded any but fringe constituencies was during the high tide of the progressive movement that ebbed with World War I.

Leland Rayson, an independent liberal member of the Illinois House of Representatives from 1965 to 1977, once said of McGovern in ’72 that the senator was “guilty of premature morality.” There was a lot of Christian idealism in his approach to politics – he had considered becoming a minister as a youth – but unlike today’s Christian politicians, he applied his faith to his own public beliefs rather than try to apply it to everyone else. He thought hunger in a fat world was wrong. President Kennedy made him the first director of the Food for Peace Program, by which we in effect tried to bomb the Third World into submission with 50-pound bags of rice. McGovern also believed that fighting wars without good reasons was evil.

McGovern was an unlikely man to carry the party banner that year. Ed Muskie of Maine was the likely candidate. But McGovern’s people had mastered, indeed McGovern himself had helped write, the new delegate selection rules the Democrats put in place after the debacle of Chicago 1968. For the first time, convention delegates ran in the primaries, and McGovern’s grassroots organization piled up more delegates pledged to his nomination than anyone else’s.

Few of them, alas, were from Illinois. His Sangamon County organization was based, as I recall, in a storefront on Capitol behind First Pres. Under Stu Whitaker, volunteers ran phone banks and bombed neighborhoods with leaflets and thus made up – or thought they did – for the indifference of the local Democratic organization. The results? Delegates pledged to McGovern placed 10th, 11th, 15th, 16th, 17th, and 18th out of a field of 20, and against Nixon, McGovern himself later lost Illinois by 875,000 votes.

His victory at the Miami Beach convention in the face of opposition from party regulars and troglodyte unionists like George Meany thus was a surprise, and left us with the wholly misleading idea that we could actually make things happen. (A note to the kiddies: Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 is still worth reading. Go to the chapters about the seating of the Illinois delegates. A million laughs.)

I supported McGovern, wrote almost perfectly unpersuasive articles in his favor, and wanted to believe that he would become president more than I would have admitted then. (I turned 24 that year, making it the first presidential election I was allowed to vote in.) It was a good time to be young. The McGovern campaign gave us something worth working for – a novelty to most of us – and its failure gave us something to learn from. Sadly, America (the America that is, not the America we made up) learned nothing. Because it imagined that a Communist lurked inside every liberation fighter, he argued, the U.S. had allowed itself to become “identified with corrupt, stupid and ineffective dictators.” Anti-terrorism has since replaced anti-Communism on our banners, but we still fall victim to the same impulse, excited by much the same kind of rhetoric, resulting in the same folly and the same terrible cost in blood treasure and honor.

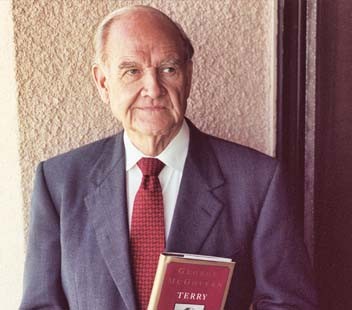

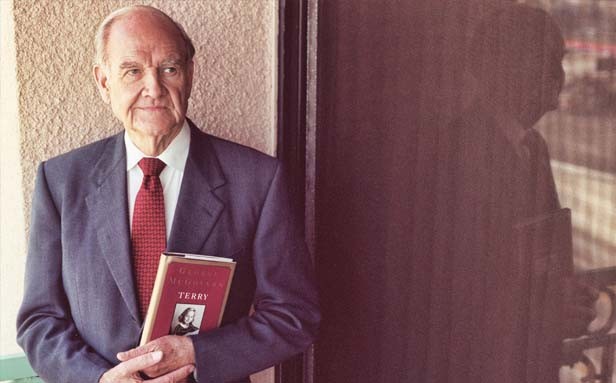

After the election, the world had little use for George McGovern. He carried on like the minister that he once thought of becoming, preaching what the world wouldn’t let him do. I changed my mind about many things in the past 40 years, but not him. “The American public doesn’t want just answers, they want easy answers,” I wrote at the time. “I don’t think George McGovern will play on that weakness, and because of that, I don’t think he’ll win….Win or lose, though I’m glad he is running.” I still am, if only because his defeat showed us what we’re up against.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].