The political speech in all its forms — from the stump harangue to the platform oration — figures significantly in central Illinois literature. Lincoln and Douglas are only our most famous Ciceros. William Jennings Bryan came to the attention of the nation because of his famous polemic against the gold standard delivered in Chicago at the 1896 Democratic National Convention, but central Illinois already knew all about him as a speaker — Bryan was class orator at Illinois College during his students days in Jacksonville. Among the more recent local masters of the craft was United Mine Workers president John L. Lewis, one of the few union leaders able to make a crowd of coal diggers cheer Shakespeare.

Three-time Illinois governor Richard Oglesby was a good enough stump speaker that people out east paid money to hear him do what he did for free for the home folks. Years as a campaigner had perfected in him the ability to say a great deal without saying anything; his classic tribute to corn (“majestic, fruitful, wondrous plant”) that he delivered at the Fellowship Club in Chicago in 1894 raised puffery to poetry. Oglesby also could be funny. “These Democrats undertake to discuss the financial questions,”he once quipped. “They oughtn’t to do that. They can’t possibly understand it. The Lord’s truth is, fellow citizens, it is about all we Republicans can do to understand that question.”

Then there was U.S. Senator Everett Dirksen, Pekin’s gift to the entertainment world. Like Lincoln, Dirksen was a reader who drew upon the Bible, although unlike Lincoln, Dirksen actually spent time in a pulpit. Also like Lincoln, Dirksen had more than a bit of the actor in him. Lance Morrow in Time detected some of W.C. Fields in the elder Dirksen. In his high school yearbook his classmates described him as suffering from “bigworditis;”reporters in later years tried to outdo him by using such words as unctuous and oleaginous to describe his style.

Until recently mid-Illinois’ best speechifyers wrote their own stuff. The hired speechwriter is a recent innovation in political discourse, and one that, like TV or polling, has not improved it. Most of them are former reporters who, having been drilled by editors into stripping their own prose of personality, find themselves ill-equipped to put personality into the prose of their boss — a big reason why speeches today, when read, all sound alike.

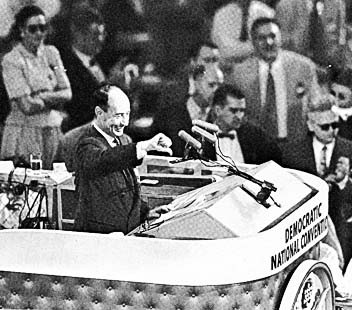

Most speechwriters relish the oblivion that is their inevitable lot, but one speech-writing shop has become modestly famous. In 1952, the Presidential campaign of then-Gov. Adlai Stevenson rented space in the local Elks Club building on Sixth Street in downtown Springfield. There they set up a sort of atelier for the writers who had come to Springfield to write Stevenson’s speeches. The main staff included W. Willard Wirtz, who would later serve as secretary of labor in the Kennedy and Johnson cabinets, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., Democratic Party activist and Harvard history professor who had already won a Pulitzer for his biography of Andrew Jackson, and John Bartlow Martin, a magazine journalist who later wrote a prize-winning biography of Stevenson. Less frequent contributors included John Kenneth Galbraith, then a Harvard economist, poet Archibald MacLeish and Harper’s editors Jack Fischer and Bernard De Voto. The Elks constituted as brainy a bunch as ever gathered in the capital to ponder matters of state, and to them Stevenson owes much of his reputation as a speechwriter.

Until recently, I would have bet my lunch that Stevenson was the last of the line of great speechifyers from Illinois, but Mr. Obama shows signs of talking his way into that list. He has shown himself a modern master of two very different types of speeches. One is the oration, of which “A More Perfect Union,” his “don’t practice what he preaches” response to his own pastor delivered at the Constitution Center in Philadelphia in March, 2008, is the best example. The other is the stump speech, few of which get any better than his admonishment on health care he delivered to Congress in September.

Yes, Obama is capable of vaporizing, and many of his speeches sound so much like sermons that it is no wonder that people doze off. But most of Lincoln’s speeches read like legal briefs, which they were, in effect, and when people recall Stevenson they quote his impromptu remarks, not his formal speeches.

As an act of oratory, a political speech is rightly judged by soundness of argument or eloquence. As an act of politics, the ambition of the speechifyer is to be persuasive. The proof is in the polling, in other words, and the polls have never been a good judge of a speechifyer. Adlai and Bryan lost five presidential campaigns between them. And in that Senate race which his debates with Douglas did so much to ornament, Lincoln lost.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].