Building new businesses based on new ideas is the central axiom of the near-science of economic development. Sangamon County’s would-be Edisons in the medical field recently were invited to submit ideas for the Greater Springfield Chamber of Commerce’s Project Innovation, intended to encourage local entrepreneurs in health care. The finalist ideas, announced in May, included new computer software to create clinical portraits of patients, improved pediatric catheters and more effective orthotic inserts; the winner, announced June 9, is a biometric authentication device that allows patients to check into a health care organization and update their records much more quickly than the traditional methods available.

These days most of Springfield’s inventive souls devote themselves largely to figuring out how to park closer to the office door. Nonetheless, the capital city has a distinguished tradition of turning bright ideas into successful businesses. The names of Ludwig Gutmann, Ira Weaver, Albert Ide and George R. Bunn do not adorn local schools but they ought to. To their tinkering the city owed thriving businesses that at their peaks kept thousands of Springfield-area families in TV sets and frozen dinners.

Albert Ide ran a machine shop and foundry out of the old city Market House at 5th and Madison streets in the latter 1800s. Making heating equipment made Ide well-off – the new Illinois Statehouse was kept warm by Ide boilers – but power generation made him excited. In 1884 he took out the first of a dozen patents on his “Ideal” high-speed automatic self-oiling steam engine. The Ideal proved to be a perfect beast to do the heaving lifting when electricity generation was done via on-site generators in public buildings, streetcar lines and large hotel and office buildings in the U.S. and abroad.

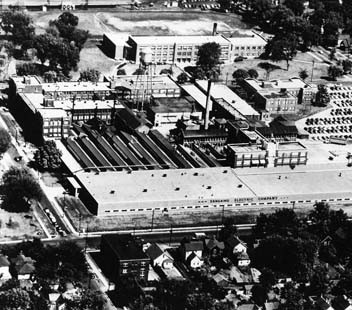

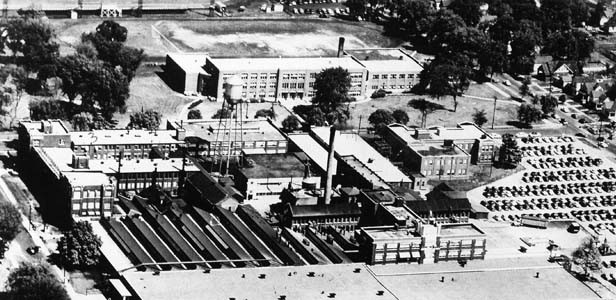

The new energy source inspired invention of a different kind in the brain of Ludwig Gutmann. He was a German electrical engineer based in Peoria who held several patents for meters to measure electricity usage. He was looking for a firm to make his induction watt/hour meters and Jacob Bunn, Jr., who was VP of Springfield’s Illinois Watch Company, was looking for new ways to make money. Gutmann’s prototype was refined into a usable product with the help of R.C. Lanphier, and Bunn and colleagues set up the Sangamo Electric Company in 1899 to make and market it. The Sangamo plant kept the north side humming from 1899 to 1978.

Ira Weaver was an Iowa farm boy who learned machinery by tinkering with the neighbors’ worn-out mowers, reapers and seed drills (and, according to family legend, by tinkering with a few that weren’t worn out). He came to Springfield as chief designer at Sattley Manufacturing Co., a maker of farm implements. On his own time he developed a chuck for high-speed drills – on such small miracles of engineering do the fates of industrial nations swing – and opened his own shop with his brother to make it. Weaver Manufacturing, which opened in 1910 at a plant on South Ninth Street, became the country’s largest manufacturer of all sorts of cunning machines for the automobile shop, from jacks to wheel aligners.

Most of these products were Weaver’s own designs. (He racked up a hundred patents in his name.) The Weavers in 1925 opened their own lab in the form of a testing garage across the street from the plant. The building still stands at 2160 S. 9th St., much abused by time and subsequent owners, but it is the closest thing Springfield has to a shrine to industrial innovation.

The Bunn-O-Matic Corporation was founded in 1957 by George Regan Bunn, who perfected the fluted commercial paper coffee filter. As inventions go, this is not the microchip or the laser. (Bunn’s contribution to caffeine consumption was to put crimps in the flimsy paper filter to make it sturdier.) Indeed the family is careful to describe him as the founder and chairman of Bunn-O-Matic, rather than as an inventor. However, from such small acorns do mighty companies grow.

These stories are misleading to the extent that they had happy endings. The Chamber should know more than most the risks in backing unproven products. The group in 1927 helped arrange the purchase of a vacant 14-acre plant at 11th and Ash by the American Radiator Company, which needed it to house their newly-developed pipe-casting operation. But the experimental casting process never worked out, and the plant lay mostly idle until Allis-Chalmers opened a branch works there.

Developing a new product is hard enough; building a firm to make and sell it at the same time is a big task. (All the above examples were developed in-house or were at least allied with existing firms.) A promising gizmo is likely to be bought by a firm that already exists, and most of those firms are in places such as Indianapolis, where an infrastructure of engineers, marketers, and investors exists that specialize in biotechnologies. Making the world a better place may prove easier to do than makingSpringfield a better place.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].