Ask Roy Maxfield how his kidney transplant changed his life, and the 62-year-old retired state employee gets emotional: "I may get verklempt," he warns. Then he recites a story that sounds like a fairytale, with a magical transformation that leads to a happily-ever-after ending.

"Some people have diabetes and lose their kidney function that way. Some hypertension, some polycystic disease. Mine is from sometime when I was a kid, I had strep throat, and the infection went to my kidneys," he says.

By the time he was 30, his kidneys began to fail. By the time he was 50, he was on dialysis —- spending four hours hooked to a machine that pumped his blood through a filter, three times a week. He discovered that he was one of the small minority of kidney patients who had trouble with the dialyzer.

"The machine and my system did not get along. I

just sat there, but my body and the machine fought each other," he

says. "I would clot off the filters, and the longer I was on it, the

higher my blood pressure would get. My blood would never get completely

clean."

At work one afternoon, his secretary told him that his doctor was on the phone. "What'd you have for lunch?" the doctor asked, and Maxfield described his meal. "Oh, we can get that out of you," the doctor replied. He told Maxfield to get himself to Memorial Medical Center; he was about to receive a kidney.

"By the time I got done talking to him, my

voice had gone up about five octaves, and they had to pick me up off the

ceiling," Maxfield says. "I could not put the phone down. I had

to have one of my compatriots call my wife, because I couldn't punch

the buttons."

His office at the time was on the corner of Jefferson and Walnut Street. To this day, he has no idea how he got from there to Memorial. All he knows is that he awoke the next morning feeling like a new man.

"It was night and day," he says.

"The three years that I was on dialysis seemed like an eternity.

Three years post-transplant was like a moment. I still can't get over

it. It's remarkable."

It has been 12 years since Maxfield received a kidney from an anonymous deceased donor. In that span, he has seen his children graduate from college, marry, and have children of their own.

"I never would've seen that,"

Maxfield says. "I tell people today that when you get a transplant,

you have a new lease on life. Someone gave you a kidney or whatever part it

was, you've got to make the best use of that part for the remainder

of your life to make it precious."

Maxfield is now an officer with the Seven County Kidney Fund, an organization that raises money to assist dialysis patients pay for ancillary needs, such as medications and transportation. He participates faithfully in annual fundraising walks. It's part of the way he tries to repay his donor.

"I don't know if other people have

that same feeling, but how do you give a person 12 more years?" he

asks. "There's not enough I can do."

Maxfield considers his transplant a miracle, but in the current medical climate, it's a mundane one: to date, more than 258,861 Americans have received a kidney transplant, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing (by comparison, there have been only 44,181 heart transplants in the U.S.).

But it was the kidney — the body's bean-shaped blood-cleansing apparatus — that paved the way for all other transplants. In a 1954 operation involving a pair of identical twins, a kidney became the first organ ever successfully relocated from one human being into another. That operation was performed at Harvard Medical School's Peter Bent Brigham Hospital by Dr. Joseph Murray. He was later awarded the Nobel Prize, for the transplant plus his subsequent work on the development of anti-rejection drugs.

Murray's successor at Brigham (now Brigham and Women's Hospital) was Dr. Alan Birtch, who moved to Springfield in 1972 to help establish Southern Illinois University's School of Medicine and the kidney transplant program at Memorial. Since then, more than 700 kidney transplants (and 17 kidney/pancreas transplants) have been performed at Memorial.

Despite this impressive pedigree, the program has now been put on ice. Three weeks ago, officials at Memorial announced that they were voluntarily suspending the transplant program. Patients on the national waiting list as well as patients in the process of qualifying to be added to the list were advised, in a letter from administrator Rebecca Anderson, to transfer to one of three other transplant programs, the nearest of which is in Peoria.

The suspension is bad news for anyone waiting for a kidney transplant. Such patients are already suffering end-stage renal disease, and many have other medical concerns, such as heart problems. Shifting appointments 75 miles north to Peoria's OSF St. Francis Medical Center (or even farther southeast to St. Louis) doesn't just mean a longer drive for these patients —- some of whom were already traveling from southern Illinois –- but also presents the challenge of coordinating their cast of local physicians (primary care doctor, diabetes specialist, cardiologist, etc.) with a transplant surgeon miles away.

The letter and subsequent published reports indicated that the suspension is due to the July retirement of Dr. Sumanta Mitra, who filled the role of transplant nephrologist -– a specialist who assists the surgeon in monitoring transplant recipients' anti-rejection medications.

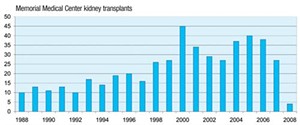

But national database statistics suggest the program was not functioning normally even before Mitra's departure. According to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, during the first six months of this year, there were only four kidney transplants at Memorial —- the lowest number in at least 10 years. By comparison, the hospital performed 25 kidney transplants last year, 38 in 2006, and 40 in 2005 (see chart, below).

Mitra's retirement was not unforeseen; he graduated from medical school almost 50 years ago. Memorial officials told the State Journal-Register the suspension occurred only because UNOS —- the organization that oversees transplant programs nationwide —- disapproved their plan to have a Springfield Clinic nephrologist serve as interim transplant nephrologist. But several medical professionals familiar with the transplant program say those officials had rebuffed an offer from a more experienced Central Illinois Kidney and Dialysis nephrologist who had volunteered to do hundreds of hours of extra work to qualify for the transplant team.

In addition, the program had over the past 12 months undergone wholesale personnel changes. Five of the nine core members of the transplant team were terminated, and two administrators were re-assigned. This shuffle occurred soon after the departure of Dr. Timothy O'Connor, the transplant surgeon who had directed the program from 1996 through 2006.

Dr. Edward Alfrey —- previously with Pennsylvania State University's School of Medicine in Hershey, Pa. —- took over O'Connor's title as director in 2007. Though O'Connor stayed on as transplant surgeon another 10 months, the two men demonstrated opposite philosophies in practically every area, from how to interview patients to their preferred immunosuppressant strategies. Their differences likewise extend to how they handle media: O'Connor agreed to be interviewed on the record for this article; Alfrey and his superiors at Memorial and at SIU's School of Medicine, where Alfrey chairs the general surgery division, all declined to answer any questions, despite repeated and specific requests delivered over a period of 10 days.

A kidney transplant program has three main functions: to identify and maintain a list of patients who are good candidates for transplant, to provide transplant surgery when suitable organs become available, and to monitor transplant recipients' health after the operation.

The first function requires a rigorous evaluation of each candidate to make sure he or she is sick enough to need a transplant, and healthy enough to get good use from it. The transplant itself requires the surgeon to make a judgment about the suitability of the donated organ and what type of drug therapy should be administered afterward to prevent the recipient's body from rejecting the organ. The final function — monitoring the transplant patient's health — can continue into perpetuity, as transplant recipients require blood tests at least once a month to ensure that their new organs are functioning properly.

O'Connor, now 48, was hired in 1995 by Birtch, and became director of kidney transplantation when Birtch retired the following year. Over the next nine years, O'Connor performed an average of 31 kidney and kidney/pancreas transplant procedures annually (up to 45 in the year 2000). He accomplished this feat by being on-call virtually 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for much of that time.

"I've left the wife and kids at the

beach. That's just what I did," he says. "Some people say

for your own sanity, you need to get away here and there. But . . . given

the vagaries of the [donor] system, in some cases, it's kind of like

winning the lottery to get a good kidney at an early time. So if we could

do it safely and effectively, we would do it."

In 2005, when Memorial announced it would bring in a second transplant surgeon, to also head the surgery department at SIU, O'Connor was thrilled. "I very much looked forward to it, because I would have more weekends off," he says.

The partnership between O'Connor and the new surgeon didn't develop quite the way O'Connor had envisioned. Shortly after Alfrey arrived, in August 2005, philosophical differences between the two eminently-qualified surgeons began to surface. Alfrey is the one topic O'Connor won't discuss, but interviews with several longtime patients and more than half a dozen medical professionals intimately familiar with the program chronicle a personality clash between the two doctors.

"One was head of surgery, the other was head of

transplant, and they both wanted to be boss," says Karon Morton, who

worked for Birtch, O'Connor and Alfrey in her 26 years as medical

secretary to the transplant program. "[One nurse] transferred to the

dialysis floor because she was tired of their BS. The two doctors gave

conflicting orders because they didn't talk to each other."

Some of their conflicts were simply judgment calls. For example, another nurse, who asked that her name not be used, says each of the two surgeons had his own preference about which organs to accept and how to treat recipints, with O'Connor accepting less-than-perfect matches and using more anti-rejection drugs, and Alfrey tending to accept closer matches that would need a lower level of anti-rejection drugs.

"During surgery, some doctors will give

induction therapy — a high dose of immunosuppressant that will last

30 to 45 days," she says. "That's something Dr. Alfrey

rarely did. But there's also literature out there that would support

that. So was it wrong? You could go either way on that."

Most of the conflict between the two transplant surgeons revolved around a much simpler issue: time. Alfrey instituted a policy of holding "clinic" –- appointments with potential or post-op transplant patients -– only on Tuesdays and Fridays.

"No other days, no other times, no exceptions," says another RN. In fact, Alfrey cancels some of those clinic days to make monthly trips to Colorado or California, where his friends and family live, the nurse says.

O'Connor, on the other hand, saw patients seven days a week, even if he knew he wouldn't get compensated.

"He would see patients on a Saturday. He just

did that," says Donna Boesdorfer, the social worker who screened

transplant candidates for seven years. "There wasn't an

appointment made, there wasn't a billing sheet, but he would just see

them to make sure they were doing okay."

When Alfrey did see patients, his bedside manner contrasted sharply with O'Connor's. Patients say he would appear, ask a cursory question, and then vanish.

"He'll look through your records and say

your levels are okay, got any questions? And out the door he goes,"

says Tim Mallicoat, who received a kidney in 2003, and a pancreas in 2006.

"I've seen him a couple of times, and I don't care for

him that much, but I can't do anything about him at the

moment."

Virginia Huffman, who had a kidney transplant 10 years ago, has a similar complaint about Alfrey during checkups: "If your arm fell off while you were sitting there, I don't think he'd care," she says.

Management apparently preferred Alfrey's style. In December 2006, O'Connor learned that Alfrey was replacing him as director of the transplant program. The demotion wasn't publicly announced, and as an associate professor of surgery at SIU, O'Connor stayed on as a transplant surgeon 10 months longer, until his contract at SIU expired. He then joined Renal Care Associates in Peoria, and is now a transplant surgeon with OSF St. Francis Hospital there.

A lack of "face time," as it's known in the field, isn't the most serious complaint about Alfrey. Former transplant staff members say that his strict office hours and frequent absences made it difficult to schedule appointments to get new patients approved for the transplant waiting list.

Once a patient got an appointment with Alfrey, he or she had to be approved by the patient selection committee -– a group of nephrologists, nurses and other transplant team members who met twice a month to compare notes about the health of candidates. No one could be approved without the endorsement of the transplant surgeon, and Alfrey frequently skipped these meetings. Each time he skipped, the candidates lost another two weeks that they could have been on the list.

"It would make me so mad," says one team

member, who asked not to be named for fear of jeopardizing her career.

"Patients would call and ask, 'Am I on the list yet?' and

I'd have to say, 'No, the doctor didn't come to the

meeting.' I couldn't get a patient on the list."

Once patients made it onto the list, their chances for transplant were diminished due to Alfrey's frequent trips out of town. Morton, the former medical secretary, says Alfrey wasn't like O'Connor -– willing to interrupt a vacation if a kidney became available.

"It's vital to take an organ when it's offered to you, if you have a good match," she says.

One former staff member claims that she had to decline two perfect-match kidneys due to Alfrey's travel plans.

Disgruntlement bubbled over late last year when the transplant staff had to complete Memorial's annual employee satisfaction survey. Most of the staff used the narrative section to express concerns about Alfrey. In January or February, eight of the nine employees repeated these concerns in a letter to Dr. Mark Weaver, Memorial's medical director.

"The one thing that was in that letter was that Dr. Alfrey wouldn't attend those [patient selection] meetings. He'd blow us off or he'd be out of town," says one RN.

"It wasn't us complaining about us; it

was us complaining that we couldn't get help for our patients,"

says the unit social worker, Boesdorfer. "They would call us, and

they'd be upset; it was awful."

In March, four people who signed the letter were terminated.

Despite the personnel turnover, the transplant program may have avoided the current temporary shutdown if Alfrey had approved the nephrologist who volunteered to replace the retiring Mitra. According to four medical professionals familiar with the transplant program, Dr. Ashraf Tamizuddin, a Springfield nephrologist with 22 years experience, volunteered in the spring of 2006 to take on the extra hours and responsibilities necessary to qualify as transplant nephrologist. Tamizuddin did not return phone calls seeking comment.

Guidelines for transplant nephrologists are published in the UNOS bylaws. Those bylaws list five different qualifying tracks — two involving traditional one-year fellowships, and three demanding lengthy and well-documented clinical experience. Tamizuddin, according to several sources, adjusted his clinical schedule beginning in spring 2006 to spend extra, uncompensated hours at Memorial in order to meet the standards listed in UNOS's fourth track, involving clinical work rather than a one-year fellowship.

All the clinical experience tracks require a letter of support from the director of the transplant program. In May 2007, when it became clear to Tamizuddin that Alfrey wanted only a fellowship nephrologist and nothing else, and likely wouldn't provide the necessary letter of support, Tamizuddin stopped the extra work.

Last week, when news of the program's

suspension became public, Memorial officials told the SJ-R that they had hoped to use

a Springfield Clinic nephrologist — unnamed in the article, but

apparently Dr. Sabrina Bessette, according to several medical professionals

— to serve as interim transplant nephrologist, but that UNOS had

decreed that "Memorial's program must have a transplant

nephrologist with a full year of additional training."

However, Mandy Claggett, a spokeswoman for UNOS, says holding out for a fellowship-trained nephrologist would be a choice made by an employer, not by UNOS. Under UNOS standards, all five methods (including the one Tamizuddin was pursuing) are equally acceptable.

"UNOS bylaws provide multiple ways a kidney

transplant physician can fill the formal training requirement portion . . .

to qualify to become a center's primary transplant physician,"

Claggett wrote in an e-mail. "The training requirements can be met

during a nephrology fellowship or through a combination of clinical

experience, if certain minimum conditions are met."

Memorial officials say they hope to have the transplant program fully-staffed and functional again after about three or four months. Meanwhile, patients are being referred to three other transplant programs -– two in St. Louis and one in Peoria, where, ironically, O'Connor currently works.

Roy Maxfield was the last patient of Dr. Alan Birtch, the surgeon who established Memorial's transplant program. In the ensuing 12 years — the ones Maxfield cherishes as a gift — he has come to consider most everyone associated the program his extended family. When he met Alfrey, during one of the surgeon's infamous drive-by appointments, Maxfield decided right away that someone needed to explain what patients want from their physicians.

"When I got home I wrote a two-page

single-spaced letter to Dr. Alfrey, saying that I expected more. A couple

of weeks later I get a telephone call from a coordinator saying did you

really mean this? I said yes. She said do you want me to show this to Dr.

Alfrey? I said, 'How else is he going to learn?' "

At Maxfield's next routine checkup, he

encountered Alfrey again. This time, the patient made it difficult for the

doctor to ignore him. "I just started asking open-ended

questions," Maxfield says. "He was either going to answer or

walk away."

In this way, he got five minutes of Alfrey's

time and Alfrey earned a second chance with Maxfield: "For him, that

was a long conversation."

Contact Dusty Rhodes at [email protected].