Celeste Tanner, a 30-year-old nurse, had never known anyone who had a baby in a hospital – or anyone who used drugs to dull the pain – until a month ago.

The third child and first daughter of a midwife, Tanner grew up around women who had their babies at home. She was taught that certain medications and procedures are needed for ill mothers or babies, but that birthing shouldn’t be treated as a process to “endure and get through.”

“Not all pain is bad pain, and it wasn’t the focus of the birth,” says Tanner. “The focus was the woman and her baby, and really bringing attention to their needs at the time.”

Her mother, Cat Feral, a Springfield-area midwife well-known for illegally assisting homebirths, had recently been subpoenaed by the state to release records of her patients, but still invited family, friends and the media to experience her daughter’s birth. After years of underground midwifery in Illinois, Feral first moved her family to Washington, and now lives in Oregon.

When Feral started in the ’70s, Illinois law prohibited midwives from attending homebirths unless a doctor was present. Surprisingly, not much has changed since then.

Over the years, midwifery split into two factions, each bound by different rules. Certified nurse midwives, or resident nurses who complete master’s training in midwifery, are allowed to attend births in hospitals or in a home with a doctor’s written consent. Certified professional midwives, or those like Feral who learn the profession through classes and apprenticeships, are still outlawed from openly practicing as primary care providers in either setting.

The Coalition for Illinois Midwifery has been working to secure equal rights for certified professional midwives through such legislation as the Homebirth Safety Act. This bill, introduced in January 2009, seeks to license certified professional midwives based on the credentials they receive after training, so they can practice legally alongside other state maternity care providers.

Tanner never considered being a midwife like her mother, she says, but became a nurse based on her exposure to health care. She didn’t grow up in an anti-Western medicine home, she explains; her family adhered to the belief that Western medicine isn’t always necessary.

Thirty years after her birth, she now lives in Portland, Ore., and is still helping her mother show other mothers that they have a choice.

“It’s not that they need to have homebirths, or they need to have hospital births, but they need to understand that there’s a choice out there,” Tanner says. “And it’s a viable choice, not a weird hippie choice. This is something that they can do, and it can be done safely.”

Feral was 24 years old when she had her first son in 1974.

She was living in Freeport and was horrified by conditions in area hospitals. Natural births were virtually unknown. Fathers were discouraged from attending births and mothers were discouraged from breastfeeding. Also, Feral adds, rooming in wasn’t permitted, so mothers stayed in their hospital rooms and babies were sent to the nursery.

Feral decided instead on a “do-it-yourself” birth. She couldn’t find a doctor or a midwife to attend the birth, or even any local Lamaze classes. She visited a family doctor for prenatal care, but otherwise, learned how to have a baby from books she received from the Association for Childbirth at Home, International, in California.

“I didn’t find that to be very helpful in labor,” Feral says. “I paced around the house and cussed. But he came out all pink and cute. I felt there had to be a better way.”

Feral talked to other women who wanted homebirths, away from rigid hospital protocols, and watched as a new movement began to take hold on the west coast. Feral says she was compelled to help mothers in Illinois.

“I was still nursing, and I spent three days and nights pacing the floors and praying and crying, because God was saying that someone ought to do this, and that someone is you,” she says.

“It was a felony to attend homebirths unless you were a doctor in Illinois. I didn’t go over the speed limit. I didn’t want to be a lawbreaker. I had a son. But after three days, I accepted that I had to do it.”

Feral began working with the Association for Childbirth at Home, and by the time her second son was born a year later, she was an active midwife and childbirth coach. She only knew two doctors, one in Chicago and one in southern Illinois, who would assist homebirths, she says, so at first, she drove north to deliver babies in Madison, Wis.

She first began illegally attending homebirths in southern Illinois, and later moved to Springfield to support the growing number of women who chose midwives over doctors. Sojourn Shelter and Services, Inc., hired her as a health counselor, she says, with the understanding that she would be “on call” to help pregnant women.

Mary O’Kiersey, who now lives in Chicago, was one of these women. She called on Feral, she says, because she didn’t trust hospitals. O’Kiersey was afraid of them as a child, and her distrust only deepened as an adult after her mother told her that she was drugged and kept from nursing all four of her children in the hospital.

“I just don’t feel comfortable with Western doctors and Western medicine,” O’Kiersey says. “They over-interfere, don’t tell people what’s going on and don’t allow people to be part of their own health care experience. With Cat, I didn’t feel that. I felt like she was there to help me, not to take over.”

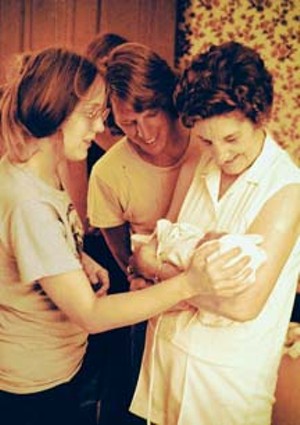

Feral helped O’Kiersey pick a birth team, which included her mother and a brother who flew in from California. They attended several of Feral’s childbirth classes and learned an emergency plan in case O’Kiersey needed to be transported to the hospital. In August 1979, after being in labor for 12 hours, O’Kiersey had her first baby girl at her home in Pawnee.

If O’Kiersey had experienced complications, Feral would’ve sent an apprentice with her to the hospital. Neither O’Kiersey nor the apprentice could mention that Feral had been involved in the homebirth.

Feral had become an advocate for patients’ rights, appearing in public and on talk shows to promote, among other things, women’s right to nurse their babies and their husbands’ right to stay with them in the delivery room.

Her public advocacy led to an investigation, she says, and in the fall of 1977, she was subpoenaed by the state of Illinois for attending homebirths as a midwife. Feral was asked to supply records listing everyone who had attended her childbirth classes, as well as anyone who attended homebirths.

Feral expected a search warrant to follow, she says, so she stopped keeping records and gave all prenatal and labor records to her patients.

“In a way, it made me a more conscientious midwife,” Feral says. “I never lost a baby. I never had a birth injury that caused long-term damage. And I certainly never lost a mother.

“Probably having started midwifery being terrified of being arrested helped to make me more careful. I would like to think that I would’ve been anyway, but it didn’t hurt that I was nervous.”

“Most OBs probably would not back up a lay midwife, and actually, because of the feeling at the time, I was unable to officially back her up,” Nichols-Johnson says. “That would have been approving her practice.”

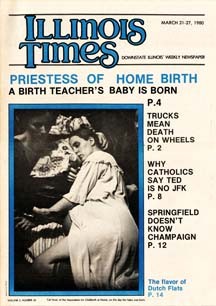

Sangamon County also disapproved of Feral’s practice, refusing to give her daughter a birth certificate. Years later, when Tanner was 13 and needed a delayed birth certificate for her driver’s license learner’s permit, Feral used a copy of the 1980 Illinois Times article to prove her existence.

Feral’s house was never searched and she was never arrested, but after she moved to Washington State in 1981, she heard that a few of her apprentices had been arrested for assisting homebirths. The state’s case against her was eventually dropped in 1982.

The same year, the Association for Childbirth at Home asked her to travel around the country to conduct five-day intensive seminars for midwives-in-training. She went from direct service, she says, to impacting hundreds more babies by teaching new midwives.

Feral had her fifth and final child in a hospital in 1988.

She had moved into a new house the day before she went into labor, so having a baby there was out of the question. Since Feral had attended births as a midwife in the hospital, she says, she was comfortable.

She was not drugged. She was attended by a midwife, and had immediate access to a pediatrician. She had her children by her side, and she was not separated from her new baby.

“I had no problem with being in the hospital,” Feral says. “I wasn’t opposed to hospitals — I’ve done lots of hospital births. It’s just having the choices and the control.”

Even as certified nurse midwives become more common, certified professional midwives are still mostly considered amateurs by the medical field since they don’t always receive a college education.

“Childbirth is a physiological process, and so I think that the less we interfere with it, the better,” Nichols-Johnson says. “On the other hand, fortunately we do have means of intervention if it’s necessary. We just have to choose the right time.”

The Coalition for Illinois Midwifery formed in 2000 to help increase the availability of licensed midwifery services for mothers wanting to give birth at home. Legal homebirth practices, with doctors and certified nurse midwives, are located in only five Illinois counties: Cook, Bureau, DuPage, Lake and Winnebago.

Women in other parts of the state don’t have many safe choices, says Michelle Breen, one of the coalition’s board members. They’re forced to travel to a county with a homebirth practice, stay at home and give birth unassisted or seek illegal help from a certified professional midwife.

If the General Assembly passes the Homebirth Safety Act and provides licensure to these midwives, she explains, they could help meet the need for safe, out-of-hospital maternity care in the other 97 counties.

The bill has been held up in the House, but Breen says they’ve made progress in the past few weeks. Legislators have called for more education and training for certified professional midwives, and after working with state nursing organizations, the Coalition developed a list of detailed educational requirements to include in the bill.

“We’re pushing, and I think there’s enough support throughout the community to get this bill passed,” Breen says. “We’re hoping this is the time now.”

Twenty-seven states have already regulated certified professional midwives, including Wisconsin, which passed new legislation at the beginning of March.

Feral retired from midwifery in 2001, after 25 years of actively participating in more than 2,000 births. Back in 1997, she helped pass a progressive state law in Oregon that makes licensure voluntary for midwives and provides health care reimbursement for homebirths.

She is now working as an Americorps VISTA volunteer to organize a summer food program for children and youth who are eligible for subsidized lunches during the school year. She hopes to eventually expand the program to support children’s physical, mental and social health.

“I feel very positive about it, and it’s fun because I’m working with people whose babies I’ve delivered, or the kids themselves, who are now young adults,” Feral says.

And in her free time? She recently celebrated her daughter’s 30th birthday by taking her to see Avatar.

Contact Amanda Robert at [email protected].