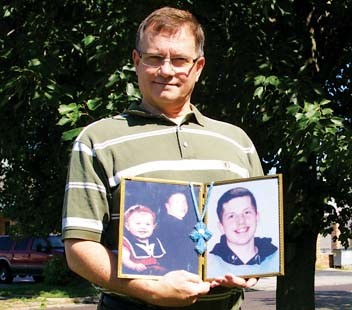

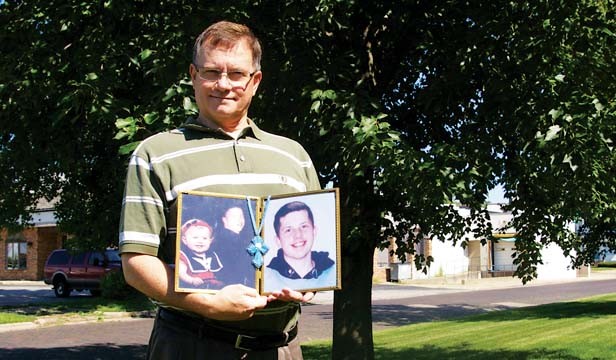

Aug. 31, 2003, is a day that Springfield’s Denny Pryor will never forget. A day that rocked his family to its core, causing an intense pain that has yet to cease. On that day, Pryor’s 18-year-old son became a statistic.

The evening was like many others, with Pryor watching Timothy kiss his six-month-old daughter goodbye before heading out for a night of “fun.” Timothy and his friends purchased some alcohol for a party they were having at a friend’s house. Later that night, the boys drove to a home in Loami, where the “party” continued into the wee hours.

Around 5 a.m. the boys piled into a car driven by Timothy’s best friend Steven (Timothy sat in the back seat), and headed back to Springfield. Less than a mile from the Loami home, Steven lost control of the car and hit a tree. There was so much force at impact that Timothy’s seat was lifted off the floorboard, slamming his body into the back of the front seat. All of his major body organs compressed, his lungs collapsed and his aorta was severed. His buddies suffered neck, shoulder and jaw injuries.

In an instant, Timothy became one of thousands who die each year in alcohol-related accidents nationwide. “The pain was excruciating. It shattered my family’s life. I can’t describe the hurt in having to arrange your child’s funeral,” Pryor tearfully explains. “Nothing prepares you for it. What is so sad is that it was 100 percent avoidable. But Timothy made a choice, and it cost him the ultimate price – his life.”

Driving under the influence (DUI), generally defined as operating a motor vehicle while impaired by alcohol or drugs, is the most frequently committed violent crime in the country. In 2003 – the year Timothy Pryor was killed – 639 people died in drunk-driving accidents in Illinois. In 2004 and 2005 the number of deaths decreased to 604 and 580, respectively. The following year, DUI deaths slightly rose to 594. Since then, the number of fatalities has continued to decrease. By 2008 – the most recent statistics available – 408 people were killed in drunk-driving accidents.

Since Timothy Pryor’s death, legislators, pushed by Mothers’ Against Drunk Drivers (MADD), law enforcement and victims’ families, passed a flurry of laws that appear to have led to a decrease in the number of drunk-driving fatalities.

While those on the front lines of the battle applaud the decrease in DUI deaths, they say even more lives can be saved through additional laws, advanced technology, educating youths and reminding the public of the true cost of drunk driving.

Picking up the pieces

Thirty-eight-year-old Danny Hicks only recalls bits and pieces of the evening that left him paralyzed from the chest down. He was 18. He remembers drinking with two friends while driving around Lake Springfield on July 17, 1990. His next memory was waking up at the hospital after a 28-day coma. Hicks soon learned that his friend lost control of the car, slamming the vehicle into a tree. Hicks was thrown through the windshield, breaking his back and causing both brain and spinal injury. He spent six months in the hospital, and another six months in outpatient rehabilitation.

“Life as I knew it drastically changed. I wanted to serve the community by becoming either a police officer or firefighter.” But that became impossible. At the time of the accident, Hicks lived with his father in a two-story home. His wheelchair prevented him from getting around in the home. That, combined with the fact that Hicks’ brain injury prevented him from being left alone, forced him to move in with his grandparents. “I had to relearn everything, including getting dressed and taking a shower. I have to use a catheter and drive a specialized van,” he says. But even with all of his injuries, Hicks was lucky. The driver and other passenger were both killed.

Today, Hicks is a community affairs specialist for Southern Illinois University School of Medicine’s Think First, a head and spinal cord injury prevention program funded by the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT). “Saving teens is a big focus of our program,” explains Hicks. “I want them to know what I went through. How my life changed. And what I lost.”

In addition to his work with Think First, Hicks travels within a nine-county area speaking on about four victim impact panels each month. Such panels are where DUI offenders are required by courts to listen to victims of alcohol-related accidents in hopes of keeping them from reoffending.

Pryor also speaks on victim impact panels. According to MADD Illinois, anecdotal evidence shows that the panels reduce recidivism among those who attend. At the end of each of his panels, Pryor shows a picture of his granddaughter Alexis, now 7 years old, and tells participants to “remember this little face when you’re thinking of getting behind the wheel after drinking.”

“It’s important that people see the reality of drinking and driving,” says Pryor, who still finds it painful to speak about his son’s accident. “It hurls you into a life of neverness. Timothy will never experience Alexis’ first words, or see her first steps, her first Christmas, her first birthday, her first day of school, or her first school program. I want the roads safe for her,” Pryor states.

Getting tough

Illinois DUI laws – said to be among the toughest in the nation – are designed to punish those who drink and drive, and to deter others from committing the crime. It’s reasonable to conclude that tougher laws and stricter penalties are largely responsible for the decrease in alcohol-related fatalities.

In the past decade the state has doubled suspension periods, increased the amount of fines, restricted “court supervision” as a penalty to once in a lifetime, and imposed mandatory prison sentences, license revocation and community service for repeat offenders.

The state has also passed laws suspending driver’s licenses for those who receive DUI arrests in another state; added penalties for individuals driving with blood-alcohol content (BAC) of .16 or above; and provided for the seizure or forfeiture of vehicles for repeat offenders who drive illegally during their suspension periods.

Last year, Illinois became one of only a handful of states requiring first-time DUI offenders to install Breath Alcohol Ignition Interlocks (BAIID) in their vehicles in order to continue driving while their licenses are suspensed. BAIID is a small breathalyzer installed on the dashboard of a vehicle to measure a person’s BAC. Blowing a .025 BAC or higher prevents the car from starting. Once a vehicle is started, a person is free to drive; however subsequent blows are required along the way. The ignition interlock replaces the Judicial Driving Permit that allowed offenders to drive only during specific hours.

Prior to the 2009 law, approximately 3,000 devices were installed on vehicles driven by repeat offenders. Now there are more than 5,000 devices installed on vehicles. “This was huge,” says Susan McKeigue, MADD Illinois executive director, adding that 50 to 75 percent of the DUI offenders continue driving after their arrests. “With the BAIID, our roads are much safer.”

According to Susan McKinney, IDOT’s BAIID administrator, studies show that recidivism is reduced by 81 percent while the device is on an offender’s vehicle, but decreases to 62 percent once it is removed. “We definitely believe that the BAIID devices help modify behaviors, which in turn prevents fatalities,” she stated.

But passing laws is only one piece of the puzzle. Enforcement is another. And police officers are indeed enforcing the laws. Each year, approximately 50,000 people are arrested by state and local authorities for driving under the influence in Illinois, and on average 2,560 teens lose their driver’s licenses through the state’s “Use It and Lose It” law, which imposes lengthy suspensions for underage drinkers with even a trace of alcohol in their systems.

Statistics show that most DUI offenders have a BAC of about .16 – twice the legal limit – at the time of the arrest, and 80 percent of those arrested are first-time offenders. At least it is the first time they have been caught. According to MADD, by the time a person receives the first DUI arrest, he or she has driven drunk more than 80 times.

The Illinois State Police reports 9,702 DUI arrests in 2008. In 2009 the number of arrests increased to 9,996. The Springfield Police Department shows 375 DUI arrests in 2008, and 396 arrests in 2009.

MADD, as well as ISP officials, said that the increase in arrests is not the result of more people driving drunk, but it is largely due to police departments assigning officers who solely focus on drinking and driving and roadside checks. The Springfield Police Department (SPD) currently has two DUI officers, while the Sangamon County Sheriff’s Department has one.

Another key factor in reducing DUI fatalities is in the hands of the courts. Following the arrests it is up to state’s attorneys and judges to ensure that offenders pay a price. Some say that in the past the judicial system fell short, with prosecutors too quick to allow defendants to plead guilty to charges other than DUI, which have less of an impact on a person’s driving record.

Pryor, whose son Timothy died in a DUI accident, says when he began working to end drunk driving there were some obvious disparities in the way the law was applied. “I noticed that law enforcement was doing its job. But there were conflicts with the judicial system,” says Pryor. “Some judges appeared to be partial to some defendants. Others didn’t feel that drunk driving was a prisonable offense. But judges are coming around, holding offenders accountable for their actions. Plus, the state has passed laws mandating prison time for repeat offenders.”

While tough penalties are important in the fight to end drinking and driving, Pryor believes that prison is not always the best answer. He and his wife, Mary, believed this to be the case in their son’s death. The two wrote victim impact statements requesting that Steven, the driver and their son’s best friend, be sent to boot camp. “We wanted him to understand that underage drinking is serious and has hurtful consequences. We wanted him to get control of his life, and we didn’t believe that prison would help him do that,” Pryor explained.

The judge denied the request, sentencing him instead to three and one half years in prison. The Pryors appealed to the state’s attorney, who convinced the judge to grant the family’s request and to send Steven to boot camp. The Department of Corrections, however, denied Steven’s entrance into the boot camp program because it does not accept people responsible for the death of others. Steven served three years in prison.

Forging ahead

Despite stricter laws and penalties, some believe it’s unlikely that drunk driving will completely end; therefore, the focus is to get as many drunk drivers off the road as possible.

The key is for legislators, law enforcement officials, the courts and the public to work together. Lawmakers must continue to pass laws to deter people from getting behind the wheel while intoxicated.

Though the General Assembly has made lots of progress in passing laws aimed at getting drunk drivers off the road, there are several laws on the books in other states that Illinois does not have.

Illinois is one of only 10 states not requiring convicted DUI offenders to complete alcohol education programs before having driving privileges reinstated. Unlike 38 other states, Illinois does not impose liability on party hosts, holding them liable if a person has an accident after being served alcohol during a party. Other laws include mandatory training for those who serve alcohol, lower BACs for repeat offenders, anti-plea bargaining (prohibits reducing alcohol-related offenses to non-alcohol-related traffic offenses), and keg registration, which records information on those who purchase kegs, allowing the state to hold the person responsible for those who consume the alcohol.

In recent sessions, legislators refused to pass a bill that would extend DUI laws to include drivers of other motor vehicle devices, such as boats and jet skis. A bill that would have allowed police officers – upon DUI arrests – to take individuals to the hospital for blood draws, even if the arrestees refuse the test, failed to make it out of committee.

Opponents argued that the bill violates the rights of unreasonable search and seizure guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution’s Fourth Amendment. But advocates of the bill counter that the state’s implied consent law makes the blood draws fair game. Under Illinois’ implied consent law, motorists agree to submit to breath, blood and urine tests when issued a driver’s license.

Attorney Tim Timoney of Springfield, former DUI prosecutor currently representing DUI offenders, says the bill is a “prime” example of laws that are “getting real close to crossing the line” in terms of constitutional violations. Other laws, added Timoney, are pushed through without considering all aspects. “There is some middle ground that is often overlooked when passing these laws,” he stated.

For example, in recent years, the state has imposed a five-year driving suspension for second DUI convictions. Should someone with a DUI in 1981, and a clear record since the arrest, have their license suspended for five years? Timoney asks.

Pryor understands the concern that some recent laws infringe on the rights of others. However, he insists that we are all responsible for the safety of the community. “If we don’t lose our choices then we lose our lives. What should we hold most dear, choice or life?”

Increasingly, states are turning to emerging technology, such as sensored flashlights that detect alcohol, and ankle bracelets that detect alcohol through sweat, as a valuable source in the fight to end drunk driving. Tests are underway on devices that detect alcohol through fingerprints and eye movement. Also, the auto industry is exploring ways to place devices in steering wheels to detect alcohol, and in car wheels to detect swerving.

“We are committed to using technology as an ally in the fight against drunk driving,” said Henry Haupt, Illinois Secretary of State deputy press secretary. McKeigue agrees. “We need as many tools as possible to get drunk drivers off the streets.”

While many may dream of a day when no drunk drivers are on the roads, the reality is that legislators and the judicial system cannot bear the sole responsibility of ending drunk driving. Real progress comes when we stop letting our family members and friends get behind the wheel when they are intoxicated, McKeigue said. “Each of us must become personally invested. If you see a car weaving, call 911. Talk to children in junior high and let them know that drinking and driving is not cool. The cost is too much to them and to others. It is up to us to keep our roads safe.”

Jolonda Young is a former IT staff writer. She currently serves as director of Intercultural Programs and Services at Blackburn College.