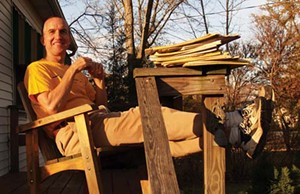

It’s been about three years since John Anderson stumbled into cable access TV. He

got a phone call from Micah Roderick — a man he had met briefly as his wife’s co-worker — who asked if Anderson would be willing to co-host a television show. Anderson

figured why not, and next thing he knew, he was a star on Just Two Guys.

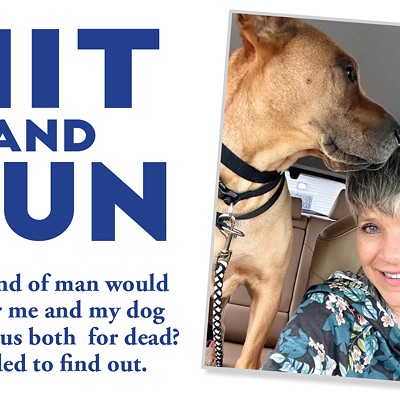

Quirky, urbane, and purposely unpolished, Just Two Guys features the clean-cut 30-something duo engaging in a variety of mostly mundane adventures: bowling, presenting “dramatic readings,” presiding over a celebrity donut-eating contest, and using marshmallows and toothpicks to create sculptures. In their debut episode, Roderick told viewers that the show will be “a couple of guys sitting around talking about topics they have no expertise in.” The show’s charm comes from having two witty, intelligent hosts who try hard to not try too hard.

“We may come up with a scene, but we don’t rehearse, there’s no editing, and we don’t re-shoot,” Anderson says.

But anecdotal evidence — and in the non-Nielsen-ized world of cable access, that’s the only kind available — suggests that Just Two Guys is one of Access 4’s “hit” shows. Anderson and Roderick’s blog (just-two-guys.blogspot.com) gets up to 100 hits per day, and the hosts find themselves getting recognized by everyone from the stocker at Lowe’s hardware to the cashier at the thrift store where they buy the coolly retro jackets they wear on their show. They’ve even been profiled by the State Journal-Register.

As their show has grown, though, Anderson has noticed that the resources available to do Just Two Guys seem to have declined. The full-time director who helped them fulfill their artistic visions, whether it meant filming outside the studio or adding a laugh-track, has been transferred away. Another director got laid off; neither position has been replaced. With only part-time staff working at the studio, shooting times have become harder to schedule, and editing help has dwindled. “I think the model they’re moving toward is just a space to do the show and the cameras and nothing else,” Anderson says.

Not that he’s complaining. He and his wife are planning to move back to Virginia, and with the public-access bug having wormed its way into his soul, Anderson has been scoping out the possibility of producing his own show in Richmond, a city more than twice the size of Springfield. To his chagrin, he’s finding no opportunities. That futile quest has given Anderson a new perspective on the free outlet that he and Roderick enjoy at Access 4.

“I think we had it pretty good here,” he says, “and didn’t even know it.”

Nationwide, public access television is becoming ever less publicly accessible. In parts of Indiana and Michigan, cable providers like Comcast are closing studios and permanently pulling the plug; in Chicago, behemoth provider AT&T is introducing the spiffy new service U-verse, offering a tantalizing array of bells and whistles while exiling all public access programming to broadcast Siberia.

Here in Springfield, the decline began about three years ago, when Access 4 moved from the University of Illinois at Springfield, where six full-time employees and innumerable students were available to direct and edit every show, to a studio at Insight where the public access channel had to make do with a fraction of its old budget and staff. Under Insight’s successor Comcast, support for the station has continued to decline, and the station now has a bare-bones staff of three part-time employees. Still, Comcast at least puts the station on the air; Springfieldians who choose AT&T for their television service currently get Dish Network — which, like all satellite services, broadcasts zero public access programming.

This same fate has befallen public access’s sister stations — educational programming like District 186’s channel 22, and government programming, like the City of Springfield’s channel 18. In industry terms, these three formats are called PEG (public,

educational, and government), and they provide purely non-commercial content,

broadcasting city council meetings or middle school choir concerts, or shows

like Access 4’s Just Two Guys and Maybelle Hall’s Meet Your Neighbor.

To understand why PEGs are disappearing, you must first get a grasp on why they

exist. Contrary to popular belief, such channels weren’t invented just to give fringe voices like The Shooting Sport host Tom Shafer a home.

The concept of PEG programming dates back decades to the birth of broadcasting, when Congress recognized that the airwaves are public property. Just as the far left end of the radio dial is reserved for non-commercial and community radio (like our WQNA 88.3 FM), so too is a certain segment of the television band dedicated to publicly-accessible free use. In Springfield, for example, the municipal channel has long been used to provide training courses for the fire department. Even now, a training course required for firefighters is shown on channel 18 every Monday at 9 a.m. and 1 and 7 p.m., so that each shift can watch. Channel 18 also broadcasts city council committee meetings, programs promoting tourism and historical information, and special events like the mayor’s inauguration.

With cable television, the public property is even more “real” or concrete than with radio: the wires that bring commercial channels like ESPN and QVC into our homes are laid in the public right-of-way along our city streets. In exchange for providing this privilege to cable companies, municipalities typically demand certain perks, such as free cable service for schools, libraries and fire stations (there are about 80 such “drops” in Springfield), along with a few spots on the dial for PEG programming. Because municipalities have such different needs, franchise agreements specifying exactly what a cable company should provide have traditionally been negotiated on a city-by-city basis.

Recent advances in technology have changed the landscape drastically: the

services provided by television and telephone providers have begun to overlap.

A few years ago, telephone companies led by AT&T began clamoring for a share of the cable television pie. Hoping to skip the

tedious and costly task of negotiating with municipal mayors, the “telcos” as they’re called in the cable industry, launched a massive campaign to open the market,

promising competition and consumer choice, or “de-regulation.”

So far, more than 20 states — including Illinois — have granted the telephone companies’ wish, establishing one-size-fits-all franchise agreements that cover entire states, overriding contracts forged between cable companies and municipalities. Illinois’ statewide franchise deal, shepherded by Attorney General Lisa Madigan’s office and finalized in 2007, was originally lauded for having more consumer protections, including public access, than neighboring Indiana’s. But now critics say it is not being enforced.

Barbara Popovic, executive director of Chicago’s CAN-TV, worked with the AG’s office to draft the legislation and was initially optimistic about the

Illinois law. Now, she says AT&T is flat out flouting the law’s plain English requirements regarding PEG. “AT&T has continued to roll out its [U-verse] system and PEG channels insisting that

it’s in full compliance with the law, which anybody could see is not the case,” she says. “I think in many respects, this really turbulent couple of years around public

media raises a question for our government: Do you see what has happened here?

You have eroded these tiny, precious resources, which in many states will just

go away, just because nobody paid attention.”

Does anybody care? It’s impossible to tell, since PEG channels, by definition, don’t sell advertising and aren’t included in Nielsen surveys. But Erik Mollberg, chair of the Alliance for Community Media in Indiana, has a survey by the local Comcast franchise to prove the appeal of the PEG channel he helps manage, Access Fort Wayne. The survey asked subscribers which channel they would be willing to delete, and only 1 percent of respondents were willing to lose a PEG channel.

“They’re not going to watch it all the time,” he admits, “but by God, they want to watch the city council meeting and our international

hockey team.”

His station gets good response on live call-in shows focused on public affairs, a show called Faith to Faith starring a minister, a mullah and a rabbi, and a monthly program called Tell America featuring Korean War veterans sharing memories. Another popular monthly broadcast is roller derby.

Such an eclectic mix is typical of most PEG stations. Brian Crowdson, who worked

at Access 4 for years and now runs his own production company in Springfield

(imaketv.com), says he loved working in public access. “There’s a lot of good people there,” he says. “Access 4 gets kind of a bad rap for being where all the weirdos are, but it’s really not that way.”

Sure there’s Shafer, whose show has evolved over the past 14 years from talking about guns

and ammo (that was the first 70 episodes) to a format he himself describes as “a grindingly thorough search for the truth” spiced with “outrageous, outspoken personal opinion.”

And there’s the strangely-popular and appropriately-named PoopTV — a solid half hour of nothing but a rock band playing in somebody’s basement. “There’s no lighting, no camera stuff, yet that show has surpassed Tom Shafer as our

most talked-about show,” Crowdson says. “People may not know the name of it, but they say ‘What’s the deal with those guys in the basement?’ ”

Just Two Guys’ Anderson is an avid fan of Poop’s resolutely low production aesthetic. “I’ve watched when the camera slid off the tripod and there was no visual at all, just the band playing in the background,” he says.

But for every esoteric hour, there’s a traditionalist like Maybelle Hall, who has introduced viewers of her show, Meet Your Neighbor, to a barbershop quartet, a chimney sweep, a Gov. Richard Oglesby impersonator, and a lady with a llama. Sangamon County Circuit Clerk Tony Libri has his own show, as does John Milhiser, Sangamon County first assistant state’s attorney.

Truth is, much of the public access time is taken up by mainstream do-gooders whose agenda is to simply do more good. About 40 of the 60 or so shows currently produced at channel 4 are religious, mostly Christian. Other nonprofits tooting their horns on public access are the Springfield Chamber of Commerce, Downtown Springfield Inc., the United Way, Henson Robinson Zoo, the Illinois Judges Association, United Cerebral Palsy, American Cancer Society and the Toastmasters Club.

“To me, it’s almost a higher purpose,” Crowdson says. “Maybe not with every show, but with a lot of them, you really get the sense you’re helping the community out. It’s not just business; it’s a community.”

For now, these shows can continue production, though Comcast vice president Rich Ruggerio suggests the cable company is doing this only out of the goodness of its heart. The new state franchise law released cable companies from their pacts with municipalities, he says, but Comcast has elected to abide by its local contracts, at least for now.

“We’ve chosen to continue to operate under franchise agreements in Illinois,” he says. “We continue to fulfill the franchise agreements and then some.”

Yet in Indiana, Comcast has closed several PEG studios, similar to Access 4.

Ruggerio calls these closures “a direct result of complying with a statewide franchising regime in which that

function is not something we’re required to do.”

AT&T currently offers no local PEG programming, but promises that PEG will be included when its new U-verse system reaches this town sometime in the next few years. A purely Internet-based service, known as IPTV, U-verse already gives Chicagoland subscribers cutting-edge features like 75 high-definition channels, plus the option of recording four programs simultaneously and watching them on any TV in their residence or on the Web or on their AT&T wireless phones.

Despite all these high-tech gizmos, AT&T can’t seem to deliver plain ol’ PEG programming in the traditional fashion. U-verse stacks PEG programming all on channel 99, which loads a Web-style menu listing 40-some different stations. Once a viewer chooses one, there’s another delay to load it in. You can’t surf to a PEG channel, the U-verse DVR can’t record it, and it can’t provide closed captioning or secondary audio (such as a simultaneous broadcast in Spanish).

Andrew Ross, the Chicago-based spokesperson for AT&T, emphasizes that U-verse is bringing viewers a richer stew of PEG programming by including streams from multiple municipalities instead of just the local public access channels. “U-verse is dramatically increasing access to this programming, from one town to hundreds, which should be the goal of everyone involved,” he says.

Popovic, the executive director of Chicago’s CAN-TV, doesn’t sound eager to take her program beyond Chicagoland borders. After all, it’s local programming, made for the local audience; all she wants is for the local

viewers to be able to watch it like they used to. “The Channel 99 scheme that AT&T presents as a plus is in fact pretty regressive, and takes away a lot of the

functionality of those channels,” she says. She’s waiting for someone to enforce the state law requiring PEG channels to be “functionally equivalent” to other all other channels.

The Federal Communications Commission probably won’t help. Last year, in response to lobbying from AT&T and Verizon claiming that local franchise agreements were so onerous they squelched competition, the FCC by a 3-2 vote issued a pair of orders paving the way for national franchising agreements. These orders have since been upheld by a federal appeals court.

This fall, the Congressional subcommittee on financial services — the body that funds the FCC — held a hearing on these orders and their effect on PEG programming. Popovic was among the witnesses; AT&T didn’t send anyone to speak on its behalf.

Mark Kirk, a Republican Congressman from Highland Park, Ill., used his opening

remarks at the hearing to chastise the telco giant. “If there was any thought by AT&T that the Republican member here at this hearing would help them out, let me

disabuse them now,” he said. “After talking to some of my communities, my view on AT&T was ‘and the horse you rode in on,’ because I think their proposal falls way short of the mark.”

He went on to urge the committee to take some action. “It does appear that AT&T is in direct violation of Illinois law,” he said.

As a result of the hearing, the subcommittee sent a letter to the FCC asking it to assess the U-verse system’s compliance with the law. The letter was sent more than two months ago. Nothing has changed.

Contact Dusty Rhodes at [email protected].