Devil’s in the details

James Earl Ray had ties to Chicago mob, says his book-promoting brother

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

Untitled Document

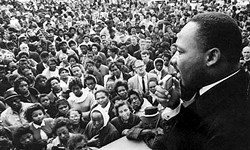

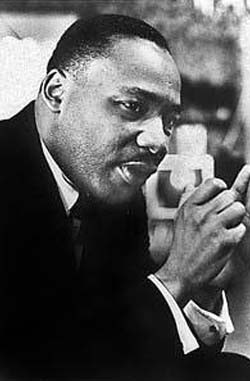

The last time John Larry Ray visited New York City was in 1965. He was between jobs, collecting unemployment benefits. While there, he remembers, Malcolm X was murdered. When he visits the Big Apple this week, he will be discussing the assassination of another black leader, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who died in Memphis, Tenn., 40 years ago, on April 4, 1968. Ray, a 75-year-old resident of Quincy, is giving media interviews in New York to promote the release of his memoir, Truth at Last, co-authored by Lyndon Barsten. Ray’s late brother James Earl Ray pleaded guilty to King’s murder in 1969 but quickly recanted his confession. The convicted assassin spent the rest of his life in the Tennessee prison system. He died of kidney failure and complications of liver disease at Nashville Memorial Hospital on April 23, 1998.

John Larry Ray, a convicted bank robber, spent more than a quarter-century behind bars himself [see “The assassin’s brother,” Nov. 29]. Truth at Last is his intriguing but meandering account, a navigation of the uncharted waters of the two siblings’ lives. “It’s like the Mississippi River,” says John Larry Ray. “You can’t stop one place and jump to another place.”

In the book, John Larry Ray asserts that his brother revealed to him that he had been ordered to shoot and kill a black soldier in postwar Germany while serving in the Army. The revelation was allegedly made in October 1974, when the two brothers shared a cell at the Shelby County (Tenn.) Jail in advance of an evidentiary hearing to determine whether James Earl Ray should be granted a trial. James Earl Ray also supposedly told his brother that the CIA had tapped him to be an intelligence asset. On the basis of this anecdote, co-author Barsten speculates that James Earl Ray was subjected to the CIA’s behavior-modification program known as MK-Ultra [see “His last score,” Nov. 29].

Much of the author’s personal knowledge of his brother’s exploits is limited to involvement in James Earl Ray’s escape from the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City in April 1967, a year before King’s murder. After the breakout, John Larry Ray says, he picked James Earl Ray up and drove him back to St. Louis.

“We stayed all night at the Catman’s in South St. Louis, says Ray, referring to Jack “Catman” Gawron, a criminal associate of the Ray brothers. The next day, he says, they met with Joe Burnett, another criminal, at a Manchester Avenue bar: “The reason we went there was to try and put some money into James’ pocket.” Burnett referred them to safecracker and burglar James “Obie” O’Brien. “We drove across the river to the Paddock Lounge in [East St. Louis] Illinois and I introduced him to Jimmie O’Brien,” Ray says. O’Brien knew the owner of the Paddock, Frank “Buster” Wortman, the East Side mob boss. O’Brien arranged for the Ray brothers to spend the night at a nearby apartment above an illegal gambling den also operated by Wortman. Meanwhile, O’Brien was supposed to check with Wortman about a proposed diamond heist. Before the details of that caper could be hashed out, however, the Ray brothers got jittery and split for Chicago.

But John Larry Ray believes that his brother maintained contact with O’Brien after their hasty departure. Later that year, James Earl Ray returned to the St. Louis area and met with O’Brien again, John Larry Ray says. He claims that his brother was then fronted an estimated $50,000. He suspects that the payoff was passed through Wortman’s organization by the Chicago mob in advance of a Canadian jewel robbery in which his brother was slated to take part. John Larry Ray says his brother gave him approximately half the money and requested that he hold $10,000 of it in case he was arrested and needed to post bond. James Earl Ray subsequently fled north of the border, but there is no indication that he participated in such a caper. After returning to the United States, he occasionally talked to his brother by phone. “He called me one time, asking about a gun,” John Larry Ray says. “I told him, if you’re looking for guns, I can get any gun you want from Ft. Campbell, Ky. I had the connection.” The last call he received from his brother before the assassination came on March 29, 1968: “He was concerned about what was going down on some type of job. He wanted to meet me.” The two arranged a rendezvous in West Memphis, Ark., on the evening of April 3, 1968, at what Ray calls a “back-alley” bar. He says he drove down from St. Louis in his cream-colored Thunderbird with a machine gun and other weapons in the trunk. But when his brother arrived, he showed no interest in purchasing guns. Instead, James Earl Ray appeared edgy and expressed apprehension about his future. In his phone call he had asked his brother to pump O’Brien for information. “I tried to contact O’Brien but I couldn’t find him,” says John Larry Ray. “I heard he was in Florida someplace.”

They sipped beer together for a couple of hours, says John Larry Ray. He says he warned his brother about the dangers of dealing with the Mafia: “I told him don’t be the one floating in the Mississippi.” During the conversation, John Larry Ray says, King’s name came up only in reference to the possibility of traffic congestion resulting from his visit to Memphis the next day. James Earl Ray worried that King’s presence in the city might somehow block his getaway plans, his brother says, and he never provided any clues about what else was making him so uneasy. They both concluded that their fears were unfounded, says John Larry Ray. When they parted, he watched his brother walk down the back alley alone. He didn’t see what kind of car his brother was driving, but he got the sense that someone was waiting for him. There is no doubt now that John Larry Ray helped James Earl Ray escape from the Missouri State Penitentiary, but the devil is in the details. Witnesses who might have confirmed John Larry Ray’s expanded version of events are dead. Moreover, Jerry Ray, John Larry Ray’s surviving brother, disputed John Larry’s account in a telephone interview from his home in McMinnville, Tenn., in October. “John will tell you he brought him [James Earl Ray] to St. Louis,” Jerry Ray says. “He didn’t bring him to St. Louis. He brought him to Chicago. You can check, if they still have the records. A day after he escaped, he was in Chicago that night, and I met him and John a day afterward at the Fairview Hotel, on Michigan Avenue in Chicago.” Asked why John Larry Ray would incorporate a stopover in St. Louis into his story, his brother replies: “I guess to dramatize the book. I don’t know.”

C.D. Stelzer wrote about the Handy Writers’ Colony of Marshall, Ill., in the Feb. 21 edition.

The last time John Larry Ray visited New York City was in 1965. He was between jobs, collecting unemployment benefits. While there, he remembers, Malcolm X was murdered. When he visits the Big Apple this week, he will be discussing the assassination of another black leader, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who died in Memphis, Tenn., 40 years ago, on April 4, 1968. Ray, a 75-year-old resident of Quincy, is giving media interviews in New York to promote the release of his memoir, Truth at Last, co-authored by Lyndon Barsten. Ray’s late brother James Earl Ray pleaded guilty to King’s murder in 1969 but quickly recanted his confession. The convicted assassin spent the rest of his life in the Tennessee prison system. He died of kidney failure and complications of liver disease at Nashville Memorial Hospital on April 23, 1998.

John Larry Ray, a convicted bank robber, spent more than a quarter-century behind bars himself [see “The assassin’s brother,” Nov. 29]. Truth at Last is his intriguing but meandering account, a navigation of the uncharted waters of the two siblings’ lives. “It’s like the Mississippi River,” says John Larry Ray. “You can’t stop one place and jump to another place.”

In the book, John Larry Ray asserts that his brother revealed to him that he had been ordered to shoot and kill a black soldier in postwar Germany while serving in the Army. The revelation was allegedly made in October 1974, when the two brothers shared a cell at the Shelby County (Tenn.) Jail in advance of an evidentiary hearing to determine whether James Earl Ray should be granted a trial. James Earl Ray also supposedly told his brother that the CIA had tapped him to be an intelligence asset. On the basis of this anecdote, co-author Barsten speculates that James Earl Ray was subjected to the CIA’s behavior-modification program known as MK-Ultra [see “His last score,” Nov. 29].

Much of the author’s personal knowledge of his brother’s exploits is limited to involvement in James Earl Ray’s escape from the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City in April 1967, a year before King’s murder. After the breakout, John Larry Ray says, he picked James Earl Ray up and drove him back to St. Louis.

“We stayed all night at the Catman’s in South St. Louis, says Ray, referring to Jack “Catman” Gawron, a criminal associate of the Ray brothers. The next day, he says, they met with Joe Burnett, another criminal, at a Manchester Avenue bar: “The reason we went there was to try and put some money into James’ pocket.” Burnett referred them to safecracker and burglar James “Obie” O’Brien. “We drove across the river to the Paddock Lounge in [East St. Louis] Illinois and I introduced him to Jimmie O’Brien,” Ray says. O’Brien knew the owner of the Paddock, Frank “Buster” Wortman, the East Side mob boss. O’Brien arranged for the Ray brothers to spend the night at a nearby apartment above an illegal gambling den also operated by Wortman. Meanwhile, O’Brien was supposed to check with Wortman about a proposed diamond heist. Before the details of that caper could be hashed out, however, the Ray brothers got jittery and split for Chicago.

But John Larry Ray believes that his brother maintained contact with O’Brien after their hasty departure. Later that year, James Earl Ray returned to the St. Louis area and met with O’Brien again, John Larry Ray says. He claims that his brother was then fronted an estimated $50,000. He suspects that the payoff was passed through Wortman’s organization by the Chicago mob in advance of a Canadian jewel robbery in which his brother was slated to take part. John Larry Ray says his brother gave him approximately half the money and requested that he hold $10,000 of it in case he was arrested and needed to post bond. James Earl Ray subsequently fled north of the border, but there is no indication that he participated in such a caper. After returning to the United States, he occasionally talked to his brother by phone. “He called me one time, asking about a gun,” John Larry Ray says. “I told him, if you’re looking for guns, I can get any gun you want from Ft. Campbell, Ky. I had the connection.” The last call he received from his brother before the assassination came on March 29, 1968: “He was concerned about what was going down on some type of job. He wanted to meet me.” The two arranged a rendezvous in West Memphis, Ark., on the evening of April 3, 1968, at what Ray calls a “back-alley” bar. He says he drove down from St. Louis in his cream-colored Thunderbird with a machine gun and other weapons in the trunk. But when his brother arrived, he showed no interest in purchasing guns. Instead, James Earl Ray appeared edgy and expressed apprehension about his future. In his phone call he had asked his brother to pump O’Brien for information. “I tried to contact O’Brien but I couldn’t find him,” says John Larry Ray. “I heard he was in Florida someplace.”

They sipped beer together for a couple of hours, says John Larry Ray. He says he warned his brother about the dangers of dealing with the Mafia: “I told him don’t be the one floating in the Mississippi.” During the conversation, John Larry Ray says, King’s name came up only in reference to the possibility of traffic congestion resulting from his visit to Memphis the next day. James Earl Ray worried that King’s presence in the city might somehow block his getaway plans, his brother says, and he never provided any clues about what else was making him so uneasy. They both concluded that their fears were unfounded, says John Larry Ray. When they parted, he watched his brother walk down the back alley alone. He didn’t see what kind of car his brother was driving, but he got the sense that someone was waiting for him. There is no doubt now that John Larry Ray helped James Earl Ray escape from the Missouri State Penitentiary, but the devil is in the details. Witnesses who might have confirmed John Larry Ray’s expanded version of events are dead. Moreover, Jerry Ray, John Larry Ray’s surviving brother, disputed John Larry’s account in a telephone interview from his home in McMinnville, Tenn., in October. “John will tell you he brought him [James Earl Ray] to St. Louis,” Jerry Ray says. “He didn’t bring him to St. Louis. He brought him to Chicago. You can check, if they still have the records. A day after he escaped, he was in Chicago that night, and I met him and John a day afterward at the Fairview Hotel, on Michigan Avenue in Chicago.” Asked why John Larry Ray would incorporate a stopover in St. Louis into his story, his brother replies: “I guess to dramatize the book. I don’t know.”

C.D. Stelzer wrote about the Handy Writers’ Colony of Marshall, Ill., in the Feb. 21 edition.

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!