The statewide murder rate continued to decline after Illinois abolished the death penalty five years ago, following a nationwide trend of decreasing crime.

However, some state lawmakers want to reinstate capital punishment in certain cases.

Illinois has a long and complicated history with the death penalty. The first execution after Illinois attained statehood occurred in 1819, and Springfield hosted its first government-sanctioned hanging in 1826. Illinois has twice reinstated its death penalty after courts struck it down: once in 1974 after a 1972 U.S. Supreme Court decision, and again in 1977 after a decision by the Illinois Supreme Court in 1975.

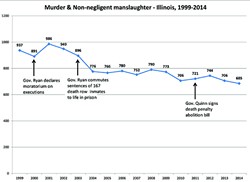

In 2000, former Gov. George Ryan declared a moratorium on executions in Illinois following the exonerations of several people who had been sentenced to death. Just before leaving office in January 2003, Ryan commuted the sentences of 167 death row inmates to life in prison.

When former Gov. Pat Quinn signed a bill abolishing the death penalty in 2011, Illinois joined 15 other states without capital punishment. Today, 20 states have no death penalty. Thirty states still have a death penalty, although four of those are under an execution moratorium by gubernatorial decree.

According to data from the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting system, Illinois has seen a decrease in murders and non-negligent manslaughter since abolishing the death penalty. However, the decrease started well before that. The FBI data shows 986 murders and non-negligent manslaughters in Illinois during 2001, a number that gradually dropped to 721 in 2011. For 2014, the most recent year for which data is available, there were 685 such crimes reported in Illinois.

Violent crime, which for the FBI count includes murder, rape, robbery and aggravated assault, dropped in Illinois both before and after the death penalty’s abolition. In 2001, there were 79,504 violent crimes in Illinois. That number dropped steadily to 55,247 by 2011 and continued dropping to 47,663 in 2014.

The data does have some limitations stemming from how crimes are reported and classified – or not reported at all. Until 2009, Illinois only reported crime data to the FBI for certain metropolitan areas, meaning statistics for the rest of the state were estimated. Additionally, the FBI previously counted sexual assault as rape only if the victim was female and force was used. Starting in 2013, the definition was widened to include any sexual penetration without consent. Crime reporting also relies heavily on police agencies, which can sometimes become political as cities try to manage their public image.

Still, Illinois’ experience with decreasing crime follows a national trend. From a peak of 1.93 million in 1992, the annual number of violent crimes nationwide has dropped steadily to fewer than 1.2 million in 2014.

Criminologists don’t agree on why crime is decreasing, attributing it to a variety of factors like an improved economy, more effective law enforcement, changing drug abuse trends and even decreased incidence of lead poisoning.

Despite the drop in crime, the death penalty remains popular. National pollster Gallup, which has tracked public opinion on the death penalty since at least 1936, recorded 60-percent support for capital punishment in every poll since 2000. The most recent poll in 2015 showed 61 percent of respondents in favor of the death penalty.

The Gallup data shows support for the death penalty has eroded significantly among Democrats in the past two decades, from 75 percent support in 1994 to a still-majority 49 percent in 2014. And although Democrats led the charge to abolish the death penalty in the Illinois General Assembly, some lawmakers within their own party fought to keep capital punishment intact.

Among them is Sen. William Haine, D-Alton, who served as a prosecutor before his election to the Illinois Senate. Haine argued against abolishing the death penalty in 2011 and has since called for reinstating it in some cases. Last year, Haine announced he would seek a new death penalty for cases involving mass killings or killing of police, children, elderly people or people with disabilities. He could not be reached for comment.

Republican state Rep. Mark Batinick from Plainfield says he’s considering a similar bill which would apply to first responders. He points to a “recent uptick” of crime targeting police, like the police shootings in Dallas and Baton Rouge earlier this year.

“If first responders don’t feel protected,” Batinick said, “it’s harder for them to protect us.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].