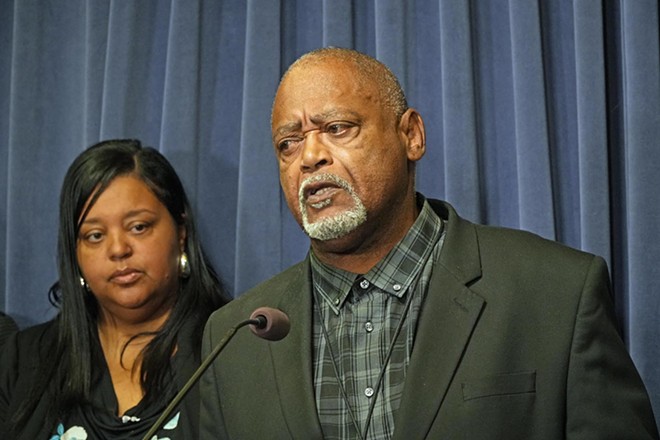

Roy Williams Jr. has seen it happen many times.

Someone is arrested and can't afford bail to get out of jail until a criminal case is resolved, whether the cost is a few hundred dollars or a few thousand.

Immediate family members who themselves are strapped for cash then try to gather money from various relatives and pool their resources. When the arrested person is released, however, Williams said many relatives don't understand why they can't get their money back right away, or even in the future, after the case is resolved and after fines, court fees and other legal costs are subtracted.

"It just causes a disruption in family relations," Williams, the Springfield City Council's Ward 3 alderperson, told Illinois Times. "It's a common thing in the Black community with bond."

These sorts of disruptions related to bond, also known as bail, ended Sept. 18 when Illinois became the first state in the nation to eliminate cash bail.

Thirty-two months after the Democratic-controlled General Assembly approved the move, law enforcement and criminal justice officials in Springfield and other parts of central Illinois said they are ready to carry out the Pretrial Fairness Act but uncertain whether crime will rise or jails will house fewer defendants awaiting trial.

"I think in three months, we'll have a very good idea," Sangamon County Sheriff Jack Campbell said.

Sangamon County State's Attorney Dan Wright, a Republican, was among most state's attorneys in Illinois who joined a lawsuit that unsuccessfully challenged the constitutionality of the law.

But Wright told Illinois Times on Sept. 18: "All stakeholders in Sangamon County are 100% committed to making sure the new law is fairly and equitably implemented while doing everything within our power to protect the public."

Going forward, some criminal defendants – including most charged with crimes of violence such as murder and gun-related offenses – will be held in jail without bail. Others will be released without paying anything and required to comply with certain conditions and show up for court hearings.

Still others no longer will be brought to the jail and booked but given notices to appear in court. And most people charged with drug-related offenses, property crimes and theft won't even be eligible to be held in jail while their cases are adjudicated.

More than 2,000 Sangamon County defendants each year will be affected by changes brought by the Pretrial Fairness Act, Wright estimated.

Circuit Judge Ryan Cadagin, presiding judge in Sangamon County, said the judicial system will be "prepared to fully implement the law and all its provisions."

Effect on public safety unclear

Campbell, a Republican and high-profile opponent of the law and the legislative process that led to its passage, said police in the county have been trained on the law's nuances, but he remains concerned about the potential for confusion over the law's interpretation by those who enforce it.

In addition to the potential for more crime by either people who are released or those who may feel less fearful of punishment, Campbell worries morale among police officers will drop and the public will lose faith in law enforcement, especially when it comes to the way police will be restricted in responding to people trespassing on private property.

Police won't be as free to remove someone from the premises, he said.

"When you take away what we have been taught to do, our entire career is 'arrest the bad guys,' 'remove them from the scene of a crime' or 'remove them from a disturbance,'" Campbell said. "Now we're afraid that we are going to disappoint our citizens because we will have to cite some people and walk away."

Williams, the Springfield alderperson, rejected the notion that the law will jeopardize public safety. He is a board member on Springfield's nonprofit Faith Coalition for the Common Good, one of many Illinois social-justice organizations in the Illinois Network for Pretrial Justice that have worked to eliminate bail for seven years.

"When we have change in our society, people resist it," Williams said. "They throw the bogeyman out there. ... We need to move forward."

Vanessa Knox, Faith Coalition's transformational justice chairperson, added: "For too long, our pretrial system punished people for being poor, creating generations of impacted people. Those days are over. This law will make us safer by ensuring people don't lose their jobs, homes or custody of their children because they couldn't afford to pay a money bond."

Other advocates said the law will increase public safety because it will provide judges more detailed information about defendants when deciding whether to keep people in jail. People won't be held unless there is evidence they will be a danger to someone else or the overall community, or unless there's evidence they plan to evade prosecution.

Illinois House Speaker Emanuel "Chris" Welch, D-Hillside, said at a Sept. 18 news conference in Chicago, "Today, Illinois is no longer criminalizing poverty, and their entire nation has its eyes on us."

The origins of the Pretrial Fairness Act

The 2021 passage of the Pretrial Fairness Act was finalized in the early-morning hours of Jan. 13, 2021, after all-night sessions of partisan debate in Springfield. It all took place while the COVID-19 pandemic was raging, many legislative hearings were held remotely, lawmakers were wearing masks and the Illinois House met in the BOS Center to promote social distancing.

The Pretrial Fairness Act was part of a broader racial-justice reform law known as the SAFE-T Act, which stands for Safety, Accountability, Fairness and Equity-Today. The Pretrial Fairness Act was upheld by the Illinois Supreme Court two months ago.

Before, during and after the Pretrial Fairness Act's passage, there were allegations from Republicans – disputed by Democrats – that the majority party rammed the measure through the legislature without enough input from law enforcement.

The SAFE-T Act was spearheaded by the Illinois Legislative Black Caucus and gained momentum after the May 2020 suffocation death of George Floyd under the knee of a Minnesota police officer, as well as the deaths of other Black people in police custody across the country.

Advocates of the act pointed to additional evidence of what they consider unequal treatment. The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights said in a 2022 report that there was a 433% increase in the number of people detained pretrial nationwide from 1970 to 2015.

Black and Hispanic defendants have higher pretrial detention rates, and more than 60% of defendants overall are detained pretrial because they can't afford to post bail, the report said.

But opponents of the Pretrial Fairness Act said crime rates in Illinois will rise as a result of more defendants at risk of violating the law being released before trial. Supporters disagreed.

Both sides have cited conflicting studies of Cook County's judicial system, which began reducing the use of bail in 2015, and other jurisdictions in other states, to bolster their arguments.

Supporters said the statewide legislation, signed into law in February 2021 by Democratic Gov. JB Pritzker, will reduce the economic and social harm that people presumed innocent until proven guilty suffer for simply being too poor to afford bail.

State Rep. Justin Slaughter, D-Chicago, said the Pretrial Fairness Act will help address the "mass incarceration crisis" that disproportionately affects poor, Black and Hispanic people and promotes generational poverty.

Because bail often is paid by defendants' families, Benjamin Ruddell, director of criminal justice policy for the ACLU of Illinois, said doing away with bail halts a system that "extracts wealth from communities that can least afford to pay."

A new system goes into effect

A key part of the law, and a change from the status quo, requires hearings to be conducted within 24 or 48 hours of arrest to determine whether a person is detained or released, if the charges make that person eligible for detainment.

Anyone else would be arrested, brought to a jail and released, or would be ticketed at the scene of an incident and receive a notice to appear in court.

If state's attorneys don't have enough information to request detention, they have up to 21 days to do so.

A person arrested before the Sept. 18 effective date and subject to a previously-set cash bond may petition the court for reconsideration of their pretrial conditions under the new law and without the option of bail. The court then could end up allowing pretrial release. Depending on the charge, petitions must be heard by the court within seven, 60 or 90 days.

Sangamon County already has had a judge in court every Sunday for bail hearings, so the county didn't have to arrange for weekend court to meet the new deadlines for detention hearings, Cadagin said.

During the week, mid-afternoon hearings will be held each weekday, if needed, when the state's attorney files requests for defendants to remain in jail.

The Sangamon County state's attorney and public defender's office have beefed up their staffs to provide judges adequate information to make a determination, Wright and Public Defender Craig Reiser said.

"Absolutely, no question – the legislation creates more work for prosecutors and defense attorneys," Wright said.

Wright said he added two paralegal positions to his staff, and Reiser said he received approval to add a paralegal to his staff.

Reiser, whose office represents the majority of people who are jailed in Sangamon County, said he is in favor of the elimination of bail.

"We start with the premise that all of our clients are innocent until proven guilty," he said. "And the decision whether an individual is detained while awaiting trial should not be determined by how much money they can post."

The Public Defender's Office may see an increase in clients. Sangamon, like some other counties in Illinois, allows private attorneys to be guaranteed payment at the conclusion of a case from at least part of any bail posted. The money is an incentive to lawyers in private practice.

Without bail, however, fewer defense lawyers may be willing to represent otherwise indigent defendants, Reiser said.

"I anticipate we may get additional cases, but we don't know," he said.

More expenses, less revenue

In total, the SAFE-T Act will cost Sangamon County about $1 million more annually, according to Sangamon County Administrator Brian McFadden. Of the total, $270,000 will be spent to fully equip all sheriff's deputies with body cameras.

New personnel for the State's Attorney's and Public Defender's Office will cost about $390,000 per year, and the elimination of bail will mean an estimated loss of $300,000 annually for the sheriff's department and Circuit Clerk's Office, McFadden said.

The sheriff's department has an annual budget of $23 million, and county government as a whole operates with a $129 million to $160 million annual budget, he said.

Property taxes won't rise, and services won't be cut in other areas, to afford the additional net expenses, McFadden said. The county has worked to become more efficient, and there are plans to install an electronic case management system for the State's Attorney's Office as part of the effort, he said.

Some of the additional costs could be offset by funding from the state for the Public Defender's Office and for body cameras. The legislature has set aside funding for those purposes, including $10 million for public defenders statewide, though McFadden said the funding either has been delayed or not yet disbursed.

Many Sangamon County officials suspect that the jail population – which currently hovers around 300 – will drop as a result of the new law. But no one knows for sure it will, and if so, by how much.

The average population would have to drop by 50 to 75 inmates for the county to realize any cost savings on jail personnel, food and related expenses, McFadden said.

Sangamon County's court services office may end up monitoring more defendants who are released rather than jailed, but Kent Holsopple, the office's director, said there are no plans to increase staff.

Many less-populous counties never before offered pretrial services but will receive them through a new Office of Statewide Pretrial Services that was created by the Illinois Supreme Court.

"It's not Armageddon"

The Administrative Office of the Illinois Courts plans to monitor caseloads and other aspects of the Pretrial Fairness Act for positive and negative effects. That monitoring will include the impact of new requirements for people facing misdemeanor and felony charges related to alleged domestic violence, according to Christine Raffaele, director of policy and systems advocacy for the Illinois Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

The coalition supported the law's passage because it helps ensure the most dangerous defendants will be held in jail pretrial. The law, Raffaele said, calls for "more robust hearings" and makes the safety of victims paramount in a judge's decision-making process on release.

The law also provides greater assurance that alleged perpetrators who violate an order of protection will be arrested and jailed until a hearing can be held, she said.

The bail that used to be set for domestic violence defendants "never made anybody safe," she said.

Sheriff Campbell, however, said he believes neighborhoods will be less safe, especially when it comes to people trespassing and disrupting the peace.

Several pieces of follow-up legislation, known as trailer bills, were passed to clarify or modify the new law. Included was a section that allows police to arrest and bring a person to jail if he or she is trespassing and refuses to leave or produce identification. The original legislation didn't allow for arrest.

But other people who would have been arrested and removed from the scene in the past now will be given a citation and could return later, prompting another call to police, Campbell said.

And people arrested for retail theft no longer are eligible for detainment. They could return to the scene of the crime after being booked, fingerprinted and released, Campbell said.

"We're afraid people will think we're not doing our job, which then can impact the morale of our deputies," he said.

People arrested for burglary of a business also aren't eligible to be jailed pretrial, unless prosecutors can prove they are at high risk of fleeing prosecution.

"My experience is the drug trade is tied to all these thefts and burglaries," Campbell said. "They're stealing anything of value that can be pawned or traded for drugs. They're going to go out and continue to commit these thefts and burglaries to feed their drug habit."

In response to complaints, the General Assembly, in one of the trailer bills, made it easier for prosecutors to ask judges to detain people charged with certain crimes if the defendants pose "a real and present threat to the safety of any person or persons in the community." Those crimes include robbery, residential burglary and kidnapping.

Under the original legislation, people charged with these crimes qualified for detention only if prosecutors could meet the high bar of proving "a high likelihood of willful flight." After legislative tweaks, the law now lists willful flight as one of several risk factors prosecutors can pick from when arguing that defendants should remain in jail while awaiting trial.

Campbell said he surveyed the background of 20 random inmates in the jail in August 2022 and found that the average number of arrests among those inmates was 26. He didn't count the number of convictions.

The sheriff said proponents of the Pretrial Fairness Act portray most jails as a "pauper's prison ... and that these are just good people that made a mistake and they should not be held in jail." But Campbell said most people in the jail have been convicted of serious violent felonies in the past.

"This tells me that when they are not locked up, they commit crimes," he said. "This is what they do for a living. If they weren't in our jail, they're not going to get up and go to work the next day. So I'm concerned about public safety in our community."

Campbell acknowledged the inherent unfairness of bail for low-income people. But he faulted supporters of the Pretrial Fairness Act for not seriously considering adopting a system similar to the federal courts, which also doesn't allow for bail – only detainment or release pretrial – and requires even more hearings in front of judges.

He also acknowledged that such a switch, which no state has made, would be more expensive than even the new system that went into effect Sept. 18.

Morgan County State's Attorney Gray Noll said he has concerns that people at risk of future crimes may be released and commit more crimes if he doesn't have information soon after an arrest, or up to 21 days later, to use in a petition for detainment.

But he said: "It's not Armageddon. There's not going to be an influx of horrible people being released."

His bigger concern is that people who were arrested for methamphetamine possession in the past and held in jail because they couldn't afford bail no longer qualify for detention pretrial.

Time in jail allowed many of them to go through detoxification behind bars, Noll said. That experience motivated many of them to get into treatment later, he said. Now, he suspects many will continue using and suffer fatal overdoses with drugs often laced with the powerful opioid fentanyl.

However, Rachel King-Johnson, director of clinical outreach for Phoenix Center, said pretrial incarceration diminishes a defendant's tolerance for illegal drugs and puts people at "a significant risk for drug overdose following release from incarceration."

Elimination of cash bail "ensures continuity of care for folks utilizing drug treatment programs, medication-assisted treatments such as methadone and suboxone, harm reduction and recovery services," she said.

Christian County State's Attorney John McWard said he is not in favor of many parts of the law and doesn't like the fact that spitting in the face of a police officer – which can be charged as aggravated battery – doesn't qualify a defendant for detainment in most cases unless there is "great bodily harm."

Defendants in mostly rural Christian County also aren't eligible to be detained if they allegedly break into a farm shed and steal property, McWard said.

"What I am concerned about is the public's trust in the judicial system prosecuting crimes," he said. "I'm concerned that people may have distrust for what we're trying to do."

Christopher Reif, chief judge of the Seventh Judicial Circuit, which includes Sangamon County, and presiding judge in Morgan County, said the new law will create scheduling challenges for rural counties in which judges juggle criminal cases in multiple counties.

"We just don't know the effect long term," he said. "Talk to me in three or six months."

The law may result in a backlog of civil cases because the criminal cases will take precedence, Reif said.

When asked whether the law could result in him releasing someone pretrial who then commits more crimes, Reif said: "I had these same concerns in the prior system. ... It's going to put more burdens on prosecutors and defense attorneys. These people are already overworked and busy."

Dean Olsen is a senior staff writer at Illinois Times. He can be reached at [email protected], 217-679-7810 or twitter.com/DeanOlsenIT.