Guy Sternberg planted his first trees when he was five years old – in his sandbox. The silver maple seeds he collected on the way home from kindergarten class would sprout and begin to grow. For the founder of Starhill Forest Arboretum near Petersburg, this tiny sandbox forest would inspire a lifetime of planting, learning and advancing knowledge about the significance of our native habitats.

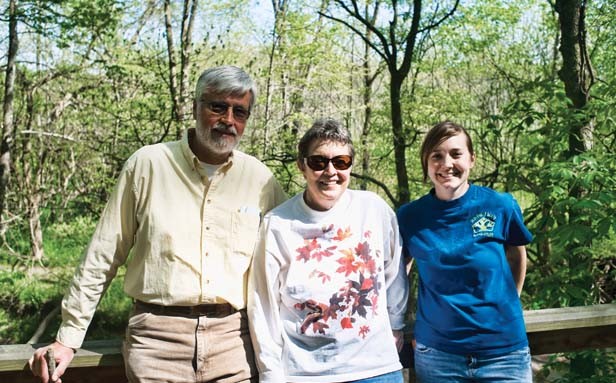

Now standing in the midst of his 48-acre arboretum that includes 2,000 types of woody plants, North America’s largest oak reference collection and a research facility, Sternberg explains the progression of his goals. “I bought this property in 1976 with the intent that we would make a little arboretum for our own use here along with the home.” Included in the “we” is his wife, Edie – his partner in a full-time passion.

As we tour the grounds, Sternberg relates how the arboretum evolved from private sanctuary to a showcase of diversity that both educates and inspires. With eyes toward the future and the continuance of their work, the Sternbergs have placed their arboretum in trust to Illinois College in Jacksonville, for which it now functions as the university’s research and teaching arboretum. The trees and habitats here are instructors of sorts, offering up stimulation for the sciences and arts. Botany, entomology, nature writing classes and art classes all are held here. Sternberg mentions that he has three interns from Illinois College starting the next day.

Along on our tour is the arboretum’s manager, Alana McKean, herself a former Illinois College intern. We move from cultivated landscape to an area of native old growth – a transition that suggests the journey Sternberg has taken. Although diverse collections of non-native species are on display at the arboretum for viewing and teaching purposes, Sternberg has also become a dedicated advocate of native habitat.

“Things evolved,” says Sternberg. “You start seeing problems with invasives. You see problems with non-natives not relating to everything around them. You see problems when you plant a tree and 10 years later in a bad winter it dies because it never experienced that kind of winter before – compared to something that has adjusted over the last 10,000 years, since the last glaciers, to all the vagaries that our climate has to offer.” He found that, once established, the oaks, hickories, ironwoods and other native trees were some of the most resilient to droughts and other weather extremes.

We reach an overlook platform with steps descending through native Illinois habitat to Rock Creek below. McKean explains that it is likely the area was not grazed during its tenure as a farm because of the steepness of the creek-side slopes. The 60 different species of woody plants that can be seen from this one overlook seem to speak of resilience and rapport. Sternberg and McKean point out trees that have been cored and dated to the Civil War era, which include white oaks, a bur oak and red oaks. Mayapples and bluebells carpet the ground beneath the tree canopy, filling the niche they evolved to fill, coexisting.

Although the arboretum includes numerous species that are not native to Illinois, Sternberg notes that native habitats such as the one before us are “no-man’s land for exotics,” with the nonnative species maintained only in the more cultivated landscape. While not all non-native species will become invasive, the wariness with which they are monitored at the arboretum is not merely a case of plant discrimination or overzealous patriotism. As Sternberg writes in his 2004 book, Native Trees for North American Landscapes: “Trees, like everything else in nature except our own species, do not recognize political boundaries, and therefore being native to a state or a county means very little.” He continues by explaining that what they do recognize are climatological barriers and geophysical barriers such as an ocean. “Native species have evolved with our climates, soils, pathogens, pollinators and associated species over thousands of years,” he explains.

So why does Sternberg, one of the founding members of the local native plant society, bother to include non-native species at the arboretum? Why worry about escapees?

“If we take them out, no one can learn if you don’t know how it spreads or what it looks like,” asserts Sternberg. “So you have to have a place to come and study those things. You have to have smallpox in some lab. You don’t want to unleash it on the world but you have to have it there so someone can study it if they need to.”

“Smallpox…Unleash it on the world.” This seems a harsh analogy until one considers the growing list of nightmarish invasive species so aggressive that complete eradication is sought at the arboretum: autumn olive, multi-flora rose, Amur honeysuckle and even the Callery (Bradford) pear tree, the star of many residential developments.

To elaborate on the invasiveness of honeysuckle, which remains green much longer during the fall season than our native species, Sternberg describes viewing the area surrounding his arboretum from the window of an airplane in early November and seeing “acres and miles” of honeysuckle that had invaded both natural areas and neighborhoods alike. Likewise, he says, the Bradford pear tree is the “next great ecological menace of the Midwest.”

“If it spreads, that doesn’t make it invasive,” states Sternberg. “But if it outcompetes and suppresses the native flora to the extent that we’re changing the ecosystem, that’s the threshold of being invasive.” He adds, “There is nothing in our hemisphere that has learned to coexist with it. Given another 100,000 years, yeah, they will.”

McKean adds that homeowners should get out and notice the species in their own backyards and not be tempted to keep invasive species just because they are green or may be acting to screen an unwanted view. “You’re not helping yourself out – you’re not helping anybody out. People need to learn what they have. You gain an appreciation for what belongs when you have to work to get rid of what doesn’t.”

As we walk down to one of seven trail bridges built to allow access across Rock Creek and visit an 80-year-old blackhaw viburnum proclaimed state champion for its size, it becomes obvious that the real beauty of the arboretum lies in the communities and the interactions, the fascinating stories and cautionary tales.

These tales and stories feature the invasive garlic mustard, eradicated at the arboretum because the roots of this plant will kill soil fungus that is beneficial to its competitors – the native bluebells, the jack-in-the-pulpits – so that we are left with nothing but garlic mustard. A story of interactions highlights a yellow-bellied sapsucker that has drilled holes into a bitternut hickory tree, causing the sap to run, which in turn attracts insects that the sapsucker will feast upon.

“People may wonder why they have not seen a particular species of bird for 10 years – say a brown creeper or redheaded woodpecker,” says Sternberg. “It’s because their habitat has been changing. It’s no longer the way it should be.” He believes the responsible homeowner should select plants that typically grow together in a native community because the native insects and birds will follow – and they will look to this guild of plants to bloom and seed in a cycle matching their needs.

It is easy to understand why students and visitors to the arboretum have been inspired to write an ode to nature or paint a tribute to a tree – or go home and create a legacy to communities of species striving to fulfill their purpose rather than settling for the newest trend or the readily available.

And it is amazing what one person along with a supportive partner can accomplish. Even one of Sternberg’s sandbox silver maples still lives in front of his family home, standing like a reminder that our choices may have consequences for decades to come. As Sternberg states in his 2004 book: “Tree planting is a lifetime investment, and such investments should be made with prudence… . Join the vanguard of modern, responsible landscape design and management. Learn from nature, plant and preserve native trees, and take pride in a job well done. It will be good for garden design, good for the environment, and good for your spirit.”

Starhill Arboretum is located at 12000 Boy Scout Trail in Petersburg. Visits can be scheduled by contacting the arboretum via their website: http://www.starhillforest.com

Jeanne Townsend Handy is a freelance Springfield writer whose husband and photographer, Tom, has been removing invasive honeysuckle upstarts from their backyard since returning from Starhill Arboretum. They may be reached at www.jthandy.com