A poet of fact

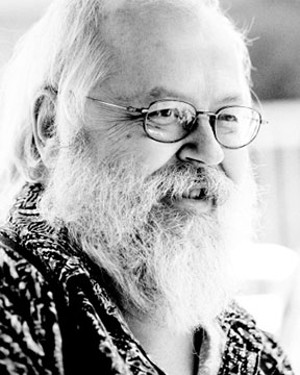

Illinois loses Lee Sandlin

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

The man who arguably was Illinois’ best writer died not long ago, and hardly anyone south of the Loop noticed. Lee Sandlin, belle-lettrist and critic, was among the contributors to Chicago’s Reader who did best what the Reader became known for doing best – long-form journalism, essays of criticism and opinion, memoirs. He suffered a mercifully quick end to a cruelly abbreviated life on Dec. 14, and Chicago suddenly became a less interesting place.

Lee’s specialty was what Wallace Stevens described (in a poem Lee adopted as his professional manifesto) as “the poem of pure reality” which some of us like to think of as the Higher Journalism. Lee called himself “just a guy who writes about stuff that happened” (one of the few times his prose proved inadequate). Sometimes the stuff that happened, happened to him. If you don’t think that a city offers opportunities for pioneer heroism on an inhospitable frontier, read “The Invisible Man,” in which the carless author treks across the wastes of O’Hare to pick up a cat. Harold Henderson, longtime IT writer and editor and Reader regular, considers that piece one of the 10 best pieces ever run by the paper.

We have Illinois writers and we have Chicago writers but those disparate worlds met in Lee. He was born in an exurban proto-town in Lake County and as an adult was a fixture in one of the small towns that make up Chicago’s North Side, but he was partly raised in Madison County. One of his signature pieces was “The Distancers,” a chronicle of the American Midwest of several generations as lived in a single house in Edwardsville that Lee revisited in 2007, which version is, happily, available in paperback. It bears comparison to William Maxwell’s stories and novels set in Lincoln and Chicago, although Lee speaks plainly where Maxwell only whispered.

The practical presses even poets, and Lee also banged out reviews and occasional critical pieces on symphonic music, on operas from Handel to Glass, on genre fiction and on TV. (Go to his website and read him as he tracks down, arrests and convicts “Law & Order” in “On TV: Disorderly Conduct.”) However, the critic in him was alive to the peculiar merits of his material, whatever the form. The detective Regular Guy, who populates the novels of our Mickey Spillanes, he noted in “The American Scheme,” was the American simpleton who shared his readers’ contempt for the city whose mysteries left them befuddled.

[His] constant stream of cynical wisecracks, his contempt for the glamour and sophistication of the villains, the way his solutions reduced everything to the most banal and animalistic motives – it all came to suggest that the Guy never

understood much about the world he had conquered. Instead, he was explaining it to the readers back home in a way that flattered their ignorance: that there wasn’t anything to these city slickers, their culture was a sham, their snobbery was a joke, their money unearned or stolen….

Many a writer would have made that the centerpiece of an essay; Lee offered it as an aside in a larger piece – hard to classify – about his father and a certain generation of American male, about growing up the son of such a man, and about the suburbs as the expression of certain notions of American life.

He was a geologist of the mundane, able to conjure lost worlds through the patient study and imaginative re-assembly of a life’s detritus. His prose is unadorned; he achieved his effects with what was said, not how he said it. The Edwardsville of “The Distancers” was to his child’s eye “a kind of eternal Tom Sawyer-ish reverie,” the place “postcard-perfect,” with “towering shade trees and well-tended hedges, placid side streets and meandering back alleys.” Just when you begin to think that you’ve been suckered into another more lyrical paean to the Midwestern small town and start skimming, he tells about climbing a willow tree and in it finding “a cicada shell stuck to a branch at its heart, like a statuette of martian jade,” and you decide that the piece will reward close attention after all.

Lee grasped that no topic is uninteresting if it is well understood. Read his “The Road to Nowhere” from 1984; you might find yourself no more comfortable on an interstate highway than you are now, but you will probably understand that unease for the first time. I thought of Lee when reading his hero Hazlitt on the conversation of authors. “An author has studied a particular point – he has read, he has inquired, he has thought a great deal upon it, he is not contented to take it up casually in common with others,” noted the Englishman. “He will either remain silent, uneasy, and dissatisfied, or he will begin at the beginning, and go through with it to the end.” Lee’s going through with it to the end enriched my understanding of things, and the possibilities of my own trade, and I wish I’d said thanks.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].

Lee Sandlin’s work can be read at http://www.leesandlin.com/ and http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/ArticleArchives?author=865639

Lee’s specialty was what Wallace Stevens described (in a poem Lee adopted as his professional manifesto) as “the poem of pure reality” which some of us like to think of as the Higher Journalism. Lee called himself “just a guy who writes about stuff that happened” (one of the few times his prose proved inadequate). Sometimes the stuff that happened, happened to him. If you don’t think that a city offers opportunities for pioneer heroism on an inhospitable frontier, read “The Invisible Man,” in which the carless author treks across the wastes of O’Hare to pick up a cat. Harold Henderson, longtime IT writer and editor and Reader regular, considers that piece one of the 10 best pieces ever run by the paper.

We have Illinois writers and we have Chicago writers but those disparate worlds met in Lee. He was born in an exurban proto-town in Lake County and as an adult was a fixture in one of the small towns that make up Chicago’s North Side, but he was partly raised in Madison County. One of his signature pieces was “The Distancers,” a chronicle of the American Midwest of several generations as lived in a single house in Edwardsville that Lee revisited in 2007, which version is, happily, available in paperback. It bears comparison to William Maxwell’s stories and novels set in Lincoln and Chicago, although Lee speaks plainly where Maxwell only whispered.

The practical presses even poets, and Lee also banged out reviews and occasional critical pieces on symphonic music, on operas from Handel to Glass, on genre fiction and on TV. (Go to his website and read him as he tracks down, arrests and convicts “Law & Order” in “On TV: Disorderly Conduct.”) However, the critic in him was alive to the peculiar merits of his material, whatever the form. The detective Regular Guy, who populates the novels of our Mickey Spillanes, he noted in “The American Scheme,” was the American simpleton who shared his readers’ contempt for the city whose mysteries left them befuddled.

[His] constant stream of cynical wisecracks, his contempt for the glamour and sophistication of the villains, the way his solutions reduced everything to the most banal and animalistic motives – it all came to suggest that the Guy never

understood much about the world he had conquered. Instead, he was explaining it to the readers back home in a way that flattered their ignorance: that there wasn’t anything to these city slickers, their culture was a sham, their snobbery was a joke, their money unearned or stolen….

Many a writer would have made that the centerpiece of an essay; Lee offered it as an aside in a larger piece – hard to classify – about his father and a certain generation of American male, about growing up the son of such a man, and about the suburbs as the expression of certain notions of American life.

He was a geologist of the mundane, able to conjure lost worlds through the patient study and imaginative re-assembly of a life’s detritus. His prose is unadorned; he achieved his effects with what was said, not how he said it. The Edwardsville of “The Distancers” was to his child’s eye “a kind of eternal Tom Sawyer-ish reverie,” the place “postcard-perfect,” with “towering shade trees and well-tended hedges, placid side streets and meandering back alleys.” Just when you begin to think that you’ve been suckered into another more lyrical paean to the Midwestern small town and start skimming, he tells about climbing a willow tree and in it finding “a cicada shell stuck to a branch at its heart, like a statuette of martian jade,” and you decide that the piece will reward close attention after all.

Lee grasped that no topic is uninteresting if it is well understood. Read his “The Road to Nowhere” from 1984; you might find yourself no more comfortable on an interstate highway than you are now, but you will probably understand that unease for the first time. I thought of Lee when reading his hero Hazlitt on the conversation of authors. “An author has studied a particular point – he has read, he has inquired, he has thought a great deal upon it, he is not contented to take it up casually in common with others,” noted the Englishman. “He will either remain silent, uneasy, and dissatisfied, or he will begin at the beginning, and go through with it to the end.” Lee’s going through with it to the end enriched my understanding of things, and the possibilities of my own trade, and I wish I’d said thanks.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].

Lee Sandlin’s work can be read at http://www.leesandlin.com/ and http://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/ArticleArchives?author=865639

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!