Q. I wondered if I could get some input with a dish

I'm trying to replicate. Did you ever try the tenderloin

sandwich at the [now closed] Sportsman's Lounge? The tenderloins

were pounded out (you could hear them pounding in the kitchen)

and breaded. How would I go about this? I'm assuming you'd

purchase pork tenderloins, but how did they pound them so thin? Also

wondered about the breading. Any advice you could give me about

preparation and frying would be appreciatedbecause my husband and high school son really miss the

sandwiches! Lori

A. I never had a tenderloin sandwich at Sportsman's Lounge, but did enjoy their traditional Springfield-style chilli. Here's some information about pounding and breading, and suggestions to hopefully get you close to the Sportsman's Lounge version — or at least one your family likes as much!

Pounding: There are three reasons to pound meat. One is to tenderize. The pounding breaks down connective tissues. It's not only used with pork, but also with other meats and cuts that might otherwise be a bit tough, such as beef round steak.

The second reason is uniform thickness. It's especially good to use with chicken breasts; otherwise the tapered end cooks more quickly than the thicker part. It's also necessary for stuffing chicken breasts. I love to butterfly a leg of lamb for the grill by removing the bone and opening the meat out, then pounding the bulkier parts so that the entire piece is roughly the same thickness. The point isn't making it thin — it ends up about 1 1/2"-2" thick, rather that it cooks evenly.

The third reason is to make the meat thinner. It's best to put the meat between sheets of waxed or parchment paper or plastic wrap. The pounding is usually done with a meat mallet or heavy skillet. For years I used cast-iron skillets. Whenever I started thwacking away, children and pets would rush from the kitchen. Then one day I broke off the handle of my best skillet — one I'd inherited from my grandmother — and decided it was time to break down and buy the mallet (they're inexpensive). Though a skillet works fine, the mallet does do a better, more controlled job; it's quieter, too. Mine, like many, has one flat side; the other has half-diamond shaped teeth for tenderizing. Pound the meat with gentle to medium force; too much can pulverize it into mush. Also, a skillet hits the thickest part first, but if you're using a mallet, it's best to start in the middle and work outward.

Even though they're called tenderloin sandwiches, the cut used for them is actually the loin. Pork tenderloins are slender strips of meat only 2-3" in diameter; it would be difficult to impossible to pound them into pieces large enough for typical "tenderloin" sandwiches. Buy center-cut boneless pork loin cut 1/2" thick, then pound to about 1/4". It can be pounded even more, but if it's too much thinner, the breading can overwhelm the meat.

Breading: Breading isn't difficult, but can be a bit messy. Meat or vegetables are first dredged (dragged through and coated) with flour that's been seasoned with salt and pepper, shaking off any excess. When breading something that's already been seasoned or marinated, omit the salt and pepper. Then it's coated with beaten egg, allowing the excess to drip off. Depending on what I'm making, I sometimes add a little minced garlic or onion to the egg. Finally, the item is dredged in breadcrumbs or alternatives such as cracker crumbs, cornmeal or even ground nuts. Grated cheese or other seasonings can also be added. After the item is coated, press it lightly into the crumbs on each side so they adhere well. Many cookbooks recommend refrigerating breaded items in a single layer for about an hour before cooking, but I haven't found it makes much difference. Cookbooks also usually recommend using one hand to dredge the items in the dry ingredients and the other hand for the egg. This is undoubtedly good advice, but somehow I always end up with my fingertips turned into little breaded lollipops. Fortunately, the breading washes off easily.

Some cookware shops and catalogues offer a set of

three pans specifically for breading, but, aside from the silliness of

having something used only occasionally by most home cooks, the pans are

too small for large items such as pounded tenderloins. In my never-ending

quest to reduce dishwashing, I put the seasoned flour and crumbs on

separate pieces of parchment or waxed paper or paper towels, and put a

large shallow pan or platter between them for the egg, which can be beaten

with a fork right on the platter.

Frying: Sportsman's Lounge probably deep-fried the tenderloins — they'd have had a large commercial deep-fryer going all the time. For home, I'd try pan-frying first, using your largest skillet with oil that's 1/4" to 1/2" deep. Whether you're pan-frying or deep-frying, the oil's temperature is crucial. Too hot, and the breading will burn before the pork is cooked; too cool, and it'll be greasy. (Austrians say that a properly cooked wiener schnitzel — almost certainly the antecedent of breaded pork tenderloins — should be so greaseless that you could sit on it for 10 seconds without getting a stain on your pants! For deep-frying, the oil needs to be 350°-375°; for pan-frying the oil should be very hot, but not smoking.

Suggestions: Experiment with various types of breadcrumbs. Dry breadcrumbs will produce a texture different than fresh breadcrumbs. The breading on any restaurant tenderloins I've had was very fine; it's possible that cracker crumbs or a commercial breading product was used. I'd also recommend trying ethereally light panko breadcrumbs, which the Japanese use for tonkatsu, their adaptation of breaded fried pork loin. It probably wouldn't be the same as Sportsman's Lounge, but panko breadcrumbs are so light and crispy that they've become the breading standard for many chefs and serious home cooks — including me. They're available at many local groceries and at Little World Mart, 2936 S. MacArthur Blvd.

Different oils/fats will affect taste as well; try different kinds to find one that most closely matches what you remember.

Good luck, and let me know how it goes!

Contact Julianne Glatz at [email protected].

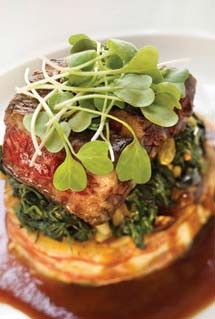

Alla Francese (French style) preparations routinely found in classic Italian-American restaurants pound the meat, but stop after the second step of the breading process, creating something lighter and different. Chicken is most common, but pork, veal, and turkey cutlets can also be made alla francese, as can butterflied shrimp. When cooking expert and author David Rosengarten attempted to trace its origins, he was unable to find a single reference to alla francese in any Italian or Italian American cookbooks. He theorizes it was created in the U.S. during the 1940s, when Italian American restaurants were regarded as inferior to "fancier" French restaurants. Whatever their origins, Rosengarten says, "…francese dishes, at their best, can offer a startling harmony of subtle flavors. A good francese is one of the world's best main course treats." I agree. This is my version.

POLLO FRANCESE

2 boneless skinless chicken breasts

flour for dredging

salt and pepper

1/4 c. finely grated pecorino romano OR parmegiano reggiano cheese

1 very large egg, beaten, plus additional if needed

1/4 c. olive oil, plus additional if needed

lemon wedges

For the sauce, optional

1/4 c. dry white wine or vermouth

1 c. chicken stock

1 T. lemon juice

2 T. chilled unsalted butter, cut into bits

2 T. chopped parsley, optional, for garnish

For the Chicken:

Pound the chicken breasts between sheets of parchment or waxed paper, or plastic wrap with a mallet or small heavy skillet until thin and of even (about 1/4")thickness. Cut each breast into 2 or 3 pieces. Season the flour with salt and pepper to taste and put on a plate or sheet of parchment. Whisk together the egg and cheese on a large shallow dish or plate. Set the flour mixture and the egg mixture next to each other.

Heat the oil in a very large skillet or two smaller skillets over medium high heat. A little additional oil may be needed, but it shouldn't be more than about 1/8" deep. While the oil is heating, quickly dredge the chicken pieces on both sides in the flour and shake off the excess. Then dip the pieces in the egg mixture, letting the excess drip off. Add to the oil when it is hot but not smoking. Be careful not to overcrowd the pan! Cook the chicken pieces until they are golden on the outside, turning once. Depending on the thickness of the chicken, this should only take about 2-3 minutes per side. When they are done, remove the cutlets and drain in a single layer on paper towels, keeping them warm. The chicken can immediately be served as is, with wedges of lemon, or with the following simple pan sauce.

For the Sauce:

Pour off the oil from the skillet and return it to the heat. Add the wine, chicken stock, and lemon juice and bring to a boil, stirring up any browned bits from the bottom. Boil the sauce until it is thickened and reduced to a glaze, about 1/2 c. Remove the pan from the heat and whisk in the butter. Depending on your preference, the cutlets can be added to the pan and coated with the sauce; served with the sauce drizzled over the top, or on the side. Sprinkle with parsley (if using) just before serving.

Serves 2 or more.