My in-laws used to tell a story about how they always cut a small piece off the end of the ham before roasting it. When someone asked what purpose this served, Great-grandmother replied, “I don’t know why the rest of you do it, but I always cut a piece off the end of the ham to be able to fit it into my roasting pan.”

Many procedures and techniques we employ in the kitchen are based on “common knowledge” which may never have withstood the test of scientific scrutiny. Most cookbooks reflect the author’s personal practices, which may not necessarily be the BEST way to prepare a dish. Books such as Harold McGee’s On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, J. Kenji Lopez-Alt’s The Food Lab: Better Home Cooking Through Science, and the periodical Cook’s Illustrated and its companion public television show America’s Test Kitchen apply scientific methods to evaluate common kitchen practices.

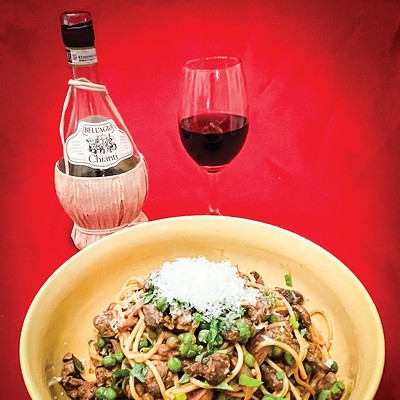

Consider the simple act of cooking dry pasta. The traditional practice is to bring a big pot of salted water to a rolling boil, which may take up to 20 minutes, and add a pound of pasta, which takes 12 to 15 minutes to cook al dente. This technique consumes a half hour of gas or electricity and puts 4 to 6 quarts of hot water down the drain. Harold McGee found that he could get a similar outcome by cooking a pound of pasta in a quart and a half of cold water in a frying pan for 15-20 minutes.

Even the simple act of whisking benefits from scientific scrutiny. I’ve always whisked in a circular motion, but experiments performed by the folks at America’s Test Kitchen reveal that circular whisking is relatively useless. For most tasks, such as making vinaigrette, roux or whipped cream, whisking side to side in a back-and-forth motion is most effective. “As the whisk moves in one direction across the bowl, the liquid starts to move with it. But then the whisk is dragged in the opposite direction, exerting force against the rest of the liquid moving toward it.” This increases the amount of “shear force” which most effectively agitates your eggs, cream or vinaigrette and creates an optimum result. The exception is whisking egg whites: a circular, looping motion lifts the liquid out of the bowl, allowing the protein structure to trap more air, due to the viscosity of the egg whites clinging to the tines of the whisk.

I’ve always thought that the correct way to pan sear meat was to preheat the skillet, add oil and get it real hot, and then add the meat. This method works very well for steak, but how about chicken or salmon?

Before I answer that question, let me state that I used to be grossed-out by poultry or fish skin. Whenever I cooked salmon, I’d end up eating the flesh and leaving the skin behind. The same with fatty, rubbery chicken skin. My attitude towards skin changed the day I had an “Oktoberfest” dinner at Chicago’s famed Berghoff Restaurant and was served a duck thigh with shatteringly crispy skin and moist tender meat. The skin was what I remembered enjoying the most. A while back I heard that in Japan, fish skin was considered a delicacy, but it wasn’t until I experienced the crispy-skinned salmon at Springfield’s Vele restaurant that I became a lover of fish skin.

So the answer to how to achieve beautiful crackly-skinned chicken or salmon at home is surprisingly counterintuitive: “Starting the chicken skin side down in a cold skillet lets the fat render slowly and results in the crispiest skin imaginable,” according to Bon Appétit magazine’s senior food editor Chris Morocco. By bringing both the chicken and skillet up to heat simultaneously, the skin is given enough time to render its fat and get nice and crispy without overcooking the flesh. Bon Appétit’s associate web editor Alex Delany applies the same approach to salmon: simply put some olive oil in a cold pan, place the salmon skin-side down and turn on the heat to high while pressing down with a fish spatula.

Before elaborating any further, let me address any concerns you might have towards the fat and calories of skin-on chicken: “Fifty-five percent of the fat in chicken skin is monounsaturated – the heart healthy kind you want more of,” says Amy Myrdal Miller, MS, TD, program director for strategic initiatives at The Culinary Institute of America at Greystone.

Crispy-skinned chicken breasts

Poke 30-40 tiny holes through the skin side with a knife or skewer. Turn over and poke 5-6 holes on flesh side.

Cover breasts with plastic wrap and pound with a meat mallet or heavy pan to a ½-inch thickness.

Sprinkle with ½ teaspoon kosher salt.

Place on a plate skin side up and refrigerate 1-8 hours.

Dry with paper towels.

Sprinkle with ¼ teaspoon black pepper.

Add 2 tablespoons of olive oil to a cold (preferably cast iron) skillet

Place chicken skin-side down and turn on heat to medium.

Cook until skin begins to brown and flesh begins to turn opaque around edges, about 15 minutes.

Flip and cook until flesh side is slightly brown and internal temperature reaches 160-165 degrees, about 3 minutes more.

Crispy-skinned salmon

Dry salmon with paper towels

Sprinkle with ½ teaspoon of salt right before cooking.

Add olive oil to a cold (preferably cast iron) pan and place salmon skin side down in a cold pan and turn up heat to high while pressing down with a fish spatula.

Flip when salmon appears cooked halfway up the side and skin releases. If skin sticks, it needs more time.

Immediately after flipping, take pan off the burner and allow the residual heat to finish cooking the flesh side.

Kitchen wisdom

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!