I first learned of the Danish restaurant Noma five years ago from an episode of Anthony Bourdain’s “Parts Unknown.” Bourdain had visited the restaurant and spent time hanging out with its head chef and founder Rene Redzepi. Noma was considered to be the best restaurant in the world, according to the panel of 800 international restaurant industry experts who compile Restaurant magazine’s annual S. Pellegrino World’s “50 Best Restaurants” list. Chef Redzepi’s focus was on creating menus from local and seasonal ingredients, especially foraged plant material, launching a movement dubbed “New Nordic Cuisine.”

Since that episode aired in 2013, I had the opportunity to apprentice and later collaborate with Chicago’s Michelin-starred Elizabeth Restaurant’s chef Iliana Regan, a forager herself. Chef Regan is a close friend of Rene Redzepi, and her restaurant put on a sold-out dinner series in Chicago last year recreating Noma’s menu. Having the opportunity to participate in preparing Noma’s most iconic dishes instilled in me a desire to delve deeper into the Noma phenomenon.

A commitment to working with fresh, local and foraged ingredients is quite a challenge during the dark, cold Scandinavian winters. I did my dental implant training in the winter of 1990 and only experienced a few hours of sunlight each day. Noma began fermenting foods as a way of being able to utilize local ingredients off-season just as our forbearers did in the days before refrigeration. In addition to the two well-known benefits of fermentation – breaking down carbohydrates and proteins into a more easily digestible form and introducing “healthy” bacteria into the gut microbiome – the Noma team discovered that exciting new flavors were being created. This prompted them to establish the not-for-profit Nordic Food Lab. The Noma Guide to Fermentation, released last month, is the offspring of that endeavor.

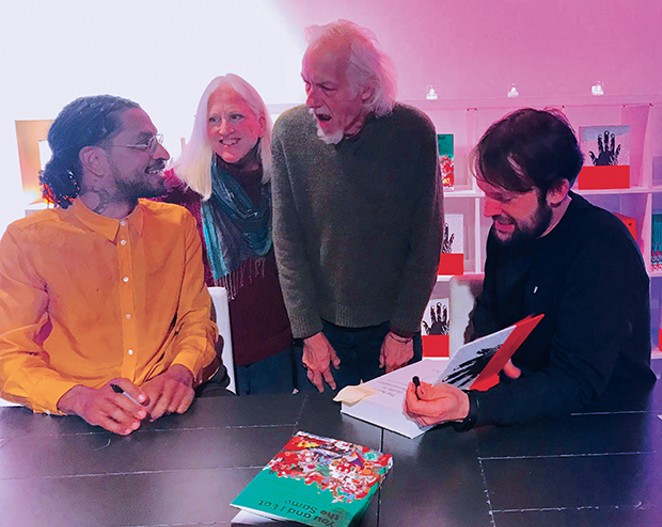

When I heard that chef Rene Redzepi and Noma’s fermentation director David Zilber would be in Chicago last month on their North American book tour, I contacted their publicist requesting an interview. In advance of the interview, I received a complimentary copy of The Noma Guide to Fermentation, one month prior to the official release date. As I perused all the different fermentation recipes, it occurred to me that I could make every recipe in the book and blog about them, just as Julie Powell did in her book titled Julie and Julia. Eyeing the small mountain of winter squash I had just brought back from The Great Pumpkin Patch, butternut squash vinegar became my first project.

The recipe begins with juicing nine pounds of squash. Before becoming vinegar, the squash must be fermented into alcohol. As compared to something like grapes, butternut squash has a low sugar content and needs help becoming squash alcohol. This help is achieved by adding a carefully measured percentage of Everclear to the juice. In order to encourage the squash alcohol to become squash vinegar, some unfiltered, unprocessed cider vinegar is added to the mix. Live bacterial cultures from the added vinegar begin the transformation of squash alcohol to squash vinegar. To speed the aerobic fermentation along, an aquarium pump is hooked up to an air stone, which is dropped into the fermentation vessel. After three weeks of bubbling away on my kitchen table, I ended up with a quart of delightful butternut squash vinegar. I posted the progress of my fermentation endeavors on my Instagram page, called it “the Noma fermentation project” and hashtagged Noma restaurant. My Instagram pictures were soon getting “likes” from chefs all over the world.

When I arrived for my interview, I saw a spark of recognition from chef Zilber and he laughed: “Hey! So you’re the one who is working through all our recipes and posting to Instagram!”

The Noma Guide to Fermentation is part textbook and part cookbook and explains seven different types of fermentation processes ranging from simple lacto-fermented blueberries to a more esoteric fish sauce like umami-packed grasshopper garum (controlled decomposition of grasshopper proteins in salt and water). The recipes are easy to follow and are supported by more than 500 photos. For those seeking to increase the healthiness and deliciousness of their cooking without resorting to chemical-laden processed flavor enhancers, this journey of rediscovery of ancient techniques is one well worth taking.

LACTO BLUEBERRIES

At the book-signing event for The Noma Guide to Fermentation, chef Zilber demonstrated how easy it is to ferment blueberries.

Ingredients:

1 kilogram blueberries

20 grams non-iodized salt

Procedure:

Rinse and dry the blueberries. Mix the salt and blueberries together in a bowl, then transfer to clean canning jars, leaving 1 inch of headspace.

Fill a zip-top bag with enough water to fill the headspace (this keeps the blueberries submerged) and cover the jar with a towel and rubber band to allow gases to escape.

Ferment in a warm place until the blueberries have soured slightly but still have their sweet, fruity perfume. This should take 4 to 5 days at 82 degrees, or a few days longer at room temperature. Start taste-testing after the first few days. When the desired level of sourness has been achieved, strain the blueberries through a fine-mesh sieve.

Use the lacto blueberries as a breakfast topping. Or puree and strain the blueberries and brush on ears of corn with a little butter, toss with roasted beets or paint on pork chops or ribs as a barbeque sauce.

The pulp and juice can be kept in the refrigerator a few days or frozen for future use.

Foundations of flavor: The Noma Guide to Fermentation

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!