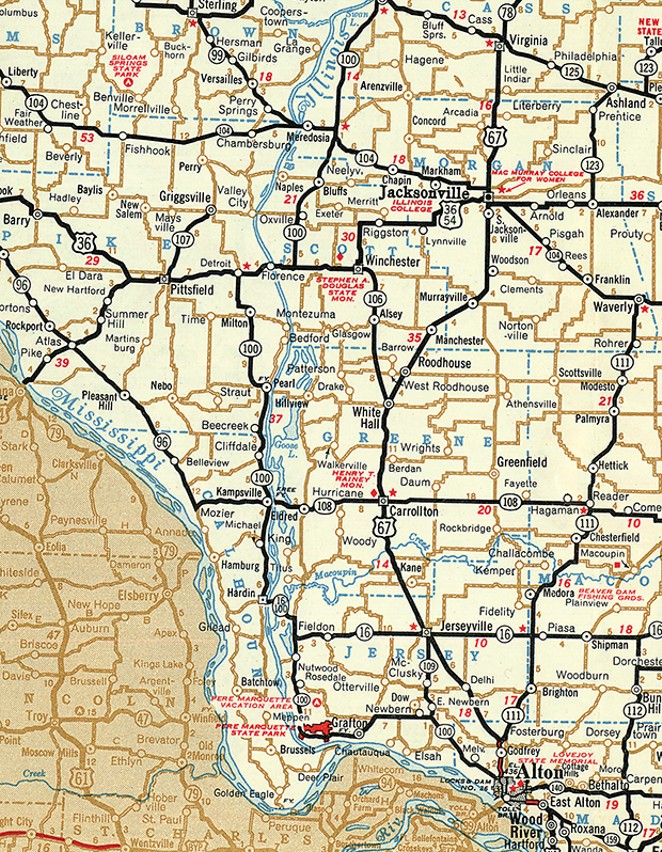

The tranquil lower Illinois River valley, roughly the 71-mile stretch from Meredosia to where the river meets the Mississippi near the southern end of Calhoun County, belies its more turbid past. In the last 50,000 years, two fluvial episodes particularly affected the formation of the river valley seen today. Prior to about 20,000 years ago, the then-mightier Ancient Mississippi River flowed through the lower half of the current Illinois River valley, which broadened its width. The second valley-shaping event, about 19,000 years ago, was the Kankakee Torrent. When an ice dam and a blockade of moraines gradually eroded and finally catastrophically gave way, unimaginably massive amounts of glacial meltwater roiled down the length of the Illinois River. While the height of the torrent likely lasted but a few days, the frigid, turbulent waters scoured the valley walls and swept the largest boulders and smallest sands downstream. The outflow soon slowed, depositing first its boulders and eventually the sands in the Illinois valley, as its force became spent.

Today, the lower reaches of the Illinois River descend barely an inch each mile. The river waters, which carry both commercial barges and pleasure boats, reside in a lock-and-dam controlled channel that now looks curiously small compared to the generally three- to four-mile span from eastern to western blufftop. (The only lock-and-dam on the lower Illinois River, built in 1939, is just north of Meredosia, with the rest of the lower river controlled by those built for the Mississippi River, such as at Alton.) The barges carry coal, petroleum and agriculture products, potentially from Lake Michigan to the Gulf of Mexico. In early historic times (and likely also in prehistoric periods), this stretch of the river carried people and goods in small watercraft from the Peoria area to the Mississippi River and the St. Louis region. There also is a tremendous amount of prehistoric archaeological evidence that the lower Illinois valley had been occupied for thousands of years by various native peoples who exploited its rich riverine resources. Pre-European occupations and activities are displayed at the Center for American Archeology’s museum in Kampsville. The Center also conducts archaeology field schools in the summer.

Like many large rivers, the Illinois overflows its banks from time to time. Many readers may well remember the last large-scale flood in 1993. In some places at its highwater mark, floodwaters stretched across the entire width of the valley. Just beyond the eastern end of the Florence bridge there is a modest highway marker thanking some of the people who worked on flood control.

Portions of the lower Illinois valley contain quarries yielding gravel and sand. The sand is from the Kankakee Torrent’s direct deposition as the flood(s) waned, from pre-flood glacial outwash (especially south of Peoria), and some subsequent wind-blown redeposition into dunes onto terraces. A modern consequence of that is some Illinois valley farmlands require irrigation because of their well-drained sandy soils.

There are a number of other local features and histories in and around the valley. Here is a small smattering.

- Pearl, in southeast Pike County, was a shirt button manufacturing center about 100 years ago, when Illinois River mussels were harvested for the iridescent qualities of their shells.

- The Eldred-Bushnell cemetery, in Greene County, is perhaps the only small-acreage set of graves that has a 55 mph thoroughfare (Hillview Road) through its middle. The accessible, flood-resistant terraces, which often are adjacent to the base of towering limestone bluffs, by necessity have become shared prime real estate for homes, roads and even cemeteries.

- If during travels in the area you lose track of Time, it would be hardly surprising. With less than 30 residents, Time, four miles west of Pike County’s Milton, is one of the state’s smallest incorporated places. However, Valley City, also in Pike County, has half as many residents and is quite possibly Illinois’ least populated incorporated place.

- The Illinois River bridge at Florence, built in 1929, was once part of U.S. Route 36 until I-72 usurped that designation via its Valley City Eagle Bridges, around 1991. The Florence bridge has a “vertical-lift through truss” design that raises for the passage of river barges.

If you plan to travel through the lower Illinois valley area, you might consider also visiting the nearby county seats of Pittsfield (Pike County) and Winchester (Scott County). Pittsfield is the self-proclaimed pork capital of the Midwest. It hosts an annual “Pig Days” festival, held in July. Abraham Lincoln occasionally stayed in Pittsfield while practicing law. Winchester was home to Stephen Douglas in the 1830s, when he was a schoolteacher, before becoming a lawyer.

Like the river through the valley, take your time to enjoy the journey.

Mark Flotow of Rochester is a frequent contributor to Illinois Heritage magazine, a publication of the Illinois State Historical Society, where this article first appeared. It is reprinted with permission.