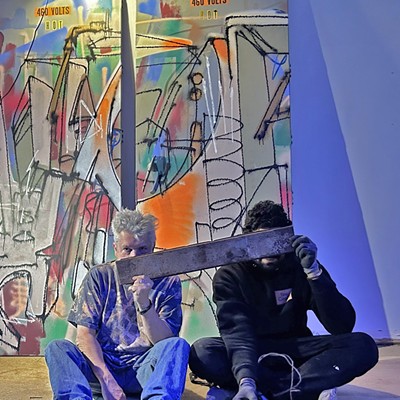

L. Brent Kington, professor emeritus at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, is widely regarded as the father of blacksmithing as an art form. The Illinois State Museum is hosting a retrospective of the 76-year-old artist, and it is well worth a visit.

When Kington and his wife, Diana, moved to Carbondale in 1961 to head the metalsmithing department at Southern Illinois University, he was making whimsical creatures cast in silver. In grad school at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, Kington had created his “little bird form,” and these cartoonish figures on three-wheeled vehicles descended from that.

The artist continued making these curious silver creatures, which became wonderful toys for his young son and daughter. His Pull Toys from the same period may remind visitors of Preston Jackson sculptures.

The artist had long been a cartoonist, and the exhibit includes three humorous watercolor cartoons entitled “A Short Autobiography Concerning People, Dogs & Experiences That Formed My Life.” Do take a look at them.

Kington the metalsmith became interested in blacksmithing after seeing the armor department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and later sought out local blacksmiths in the Carbondale area to teach him the craft. After working with the Deal brothers from Murphysboro, he decided to concentrate on blacksmithing, working in iron and steel. One of the most striking pieces from this early period is an abstract winged piece in oxidized forged steel.

In the 1970s Kington made a series of nonfunctional weathervanes, which are just elegant. The top piece of these abstract creations rests perfectly balanced on the fulcrum point of its base. Kington mastered the art of “full roll, pitch, and yaw rotation” for these kinetic pieces, according to Tayes. “Some of these pieces migrate around almost swooping like birds,” she said.

In the 1980s Kington created an Icarus series based on the idea of flight. “Icarus #25” from 1981 is stunningly beautiful and appears to be made of wood, but it’s forged steel covered with polychrome. It is a highlight of the exhibit. Kington’s interest in tribal masks is evident in the faces of these pieces. The color and texture is mesmerizing, subtle but so rich.

The artist adds texture and patina to his work in a masterful way. If you are a tactile person, this show will challenge you because you will want so much to touch some pieces.

Kington worked on a series of Crosiers beginning in 1990. Traditionally, crosiers are ornaments or staffs for bishops or archbishops, which convey rank within the church. But these five-foot-tall crosiers are birdlike, like long-legged herons or cranes which seem to soar upward. Most are svelte creatures, but the “Crosier” from 1990 is built more sturdily and emblazoned with touches of red and green and has wings. This bold crosier seems ready to take flight or do battle.

Tayes did a wonderful job of collecting the right balance of objects from different bodies of work throughout the artist’s 50-year career. Accompanying the exhibit is the catalogue L. Brent Kington: Mythic Metalsmith, which is available in the museum gift shop for $20.

Kington is regarded as almost a mythical character by former students for starting the blacksmithing program at SIU-C, for mentoring students and for his influence in the field. SIU-C offers the only Master’s of Fine Arts degree in blacksmithing in the U.S. The “Who’s Who” of metalsmiths came to this show when it first opened in Carbondale in 2007, according to Tayes.

A video featuring the artist, students and the curator running on a large plasma TV at the exhibit completes a visitor’s understanding of the significance of Kington’s career as a metalsmith. The exhibit runs through Sept. 6. After that Tayes hopes the show will travel beyond the borders of Illinois.

Ginny Lee of Springfield is a writer and photographer and longtime contributor to Illinois Times.