Nathanial Van Noy holds the dubious double distinction of being both the first murderer in Sangamon County as well as the first person to be hanged in Springfield. But it wasn’t the murder itself that made him infamous; it was the bizarre and gruesome spectacle of his hanging, when Van Noy tried to cheat death.

It all began on Aug. 27, 1826, when Van Noy’s wife did not prepare his breakfast with acceptable speed. Hungry, and reportedly drunk, Van Noy picked up a stick and struck a fatal blow to her side, killing her instantly.

He was immediately arrested and put in jail. The wheels of justice moved at lightning speed; his trial began the next day, and the day after that he was found guilty and sentenced to hang on Nov. 26.

In the intervening three months, Van Noy contemplated his grim fate and decided he was not yet ready to die. He was going to be hanged, there was no way around that fact. But perhaps there was a way to survive the hanging? He sent for a local doctor named Addison Philleo to inquire of this possibility.

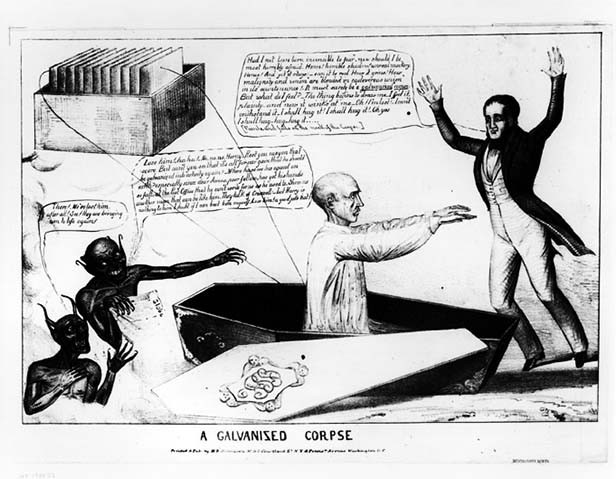

A learned man, Dr. Philleo was familiar with the work of an Italian doctor named Luigi Galvani, who had studied the effects of electricity on the human body. Philleo told Van Noy that if his neck did not break during the fall, and if he did not hang too long, there was a chance that application of a “galvanic” battery could bring him back to life.

Van Noy had nothing to lose, so he struck a deal with Dr. Philleo: should he resurrect the criminal with a battery after his hanging, Van Noy would pay the doctor. If the experiment did not work, Dr. Philleo could have Van Noy’s body to dissect for anatomical study.

This was a win-win scenario for Dr. Philleo. Corpses for medical study were extremely hard to come by in the 19th century. Indeed, many medical schools resorted to buying “black market” corpses from body snatchers to supply their anatomy labs.

On the day of the hanging, nearly the entire population of the county turned out to witness the spectacle – some coming from as far as 30 miles away. The crowd gathered at the jail on Jefferson street and followed the wagon bearing Van Noy as it turned south onto First Street and made its way to the gallows in a hollow north of the present State Capitol building.

No one in the crowd would ever forgot what happened next. As the noose was slipped around his neck, Van Noy (remembered by many as a “most excellent singer”) asked the sheriff for permission to sing. He belted out a mournful hymn, and then the cart was driven out from under him.

He didn’t die right away. He had taken Dr. Philleo’s advice and leaned forward as far as he could, which spared his neck from breaking in the fall. The sheriff, however, had heard of the arrangement between Van Noy and Dr. Philleo and wasn’t about to take any chances. He let Van Noy hang for a solid hour.

By that time there was no battery on earth that could revive Van Noy, but Dr. Philleo was as good as his word and made the attempt, anyway. Witnesses recalled that the dead man’s nerves “twitched spasmodically several times in quick succession,” but it was obvious that he was beyond all hope.

So Dr. Philleo was paid in corpse and not in cash. He wasted no time in beginning his dissection. Sources conflict as to whether he started operating right then and there, or moved the body to a nearby house, or took the body to his office downtown. However, they all agree that the good doctor began his work in full view of the revolted populace, who insisted that he move to a more secluded location.

In a young, sparsely settled county with little in the way of excitement, this event seared itself on local memory. Fifty years later, Van Noy was still being talked about by those who had been around the fateful year of his crime.

Erika Holst is curator of collections at the Springfield Art Association.