Is there any other place that figures so centrally in the social, recreational and erotic life of so many Springfieldians from so many backgrounds? A summer evening with a fishing line in the water, listening to the waves lapping on the old dam steps. Watching the moon rise over the water with a lover. Paddling about in the backwaters, where muskrats had the right of way. Motoring around the lake roads with the windows down on a muggy night

It is hard to imagine Springfield without its lake. It is even harder to imagine that Springfield actually built it. How it built it, and with what result, is the subject of a new photo history, Lake Springfield in Illinois: Public Works and Community Design in the Mid-Twentieth Century. Its authors are two well-known useful citizens hereabouts, Robert Mazrim and Curtis Mann.

Mazrim, currently archaeologist at the Illinois State Archaeological Survey, is the author of articles and six books about the archaeology and history of the Midwest, including The Sangamo Frontier: History and Archaeology in the Shadow of Lincoln. Mann describes himself too modestly as a history-minded librarian who is the manager of Lincoln Library's Sangamon Valley Collection and author or coauthor of many books, articles and pamphlets, including 10 pictorial books about the history of Springfield.

Lake Springfield is not a natural body of water, of course, but an impoundment to capture piled-up creek water. A new municipal water supply reservoir had been recommended in the 1925 city plan by damming the Sangamon River, but the planner's future would give way to the engineers, and in the early 1930s the lake was built instead on two tributary streams of the Sangamon (Salt and Lick creeks) rather than on the Sangamon itself.

Initially intended solely as a water supply, it soon served double duty as a source of steam for the boilers at a then-massive new city-owned power generating plant. The lake also offered recreational amenities that made it a summer resort for the people. It would be hard for today's Springfieldians to imagine how their municipal forebears looked forward to such pleasures, having suffered intermittently through the 1930s from hideous heat waves in an era in which residential air conditioning was rare.

To the original swimming beaches and parks and public boat docks were eventually added a nature center, golf course, zoo, an outdoor musical theater, marinas and camps. Later, the lake became known as an exclusive residential retreat, although for many years a house on the lake was the opposite of posh. The early lake houses were mostly converted summer cottages or rehabbed farmhouses and Quonset huts built to house the construction workers who built the lake. A few such structures housed poor persons' country clubs in the form of private clubs where mail carriers and firefighters, even reporters, frolicked like bankers.

The lake was a gift of Springfield's present to its future but it was delivered at some cost to the area's past. The site had been inhabited for many thousands of years. Evidence (we learn) of these occupations survive, from stone spear points, to the old quarry from which the stone for the 1837 Statehouse was built, to a remnant of the Edwards Trace, the Indian trail/wagon road that ran along the high ground that forms the eastern shore of the lake. Converting it all to a lake required that farmhouses in the flood zone be bought and torn down, roads dating to the 1800s abandoned or rerouted, and woods cleared; the village of Cotton Hill was scrubbed from the landscape, and only the name survives.

The city added as well as subtracted. The original infrastructure included some very good buildings and bridges in the form of the municipal water treatment plant, the beach house, the Lindsay Bridge, the original Lakeside power plant. In the 1930s, the city built well enough that everything survived 80 subsequent years of neglect by the city. Where things had to be replaced, they were replaced with inferior materials. (If you can buy it at Home Depot, it's good enough for the public.) As a result, every emendation made by public authorities since the water crept up to the top of the dam has made it shabbier and uglier.

In fact, the lake itself will become a relic in time. The photos in "Building a Lake" remind us that the unwatered lake, for example, is remarkably shallow. Humans build lakes and nature unbuilds them, as reservoirs gradually become filled with soil washed into them. Beneath a photo of an inundated farm that bordered the creek valley we read, "The cornfields would never be seen again." In fact, cornfields might well be seen again on, not next to, Lake Springfield.

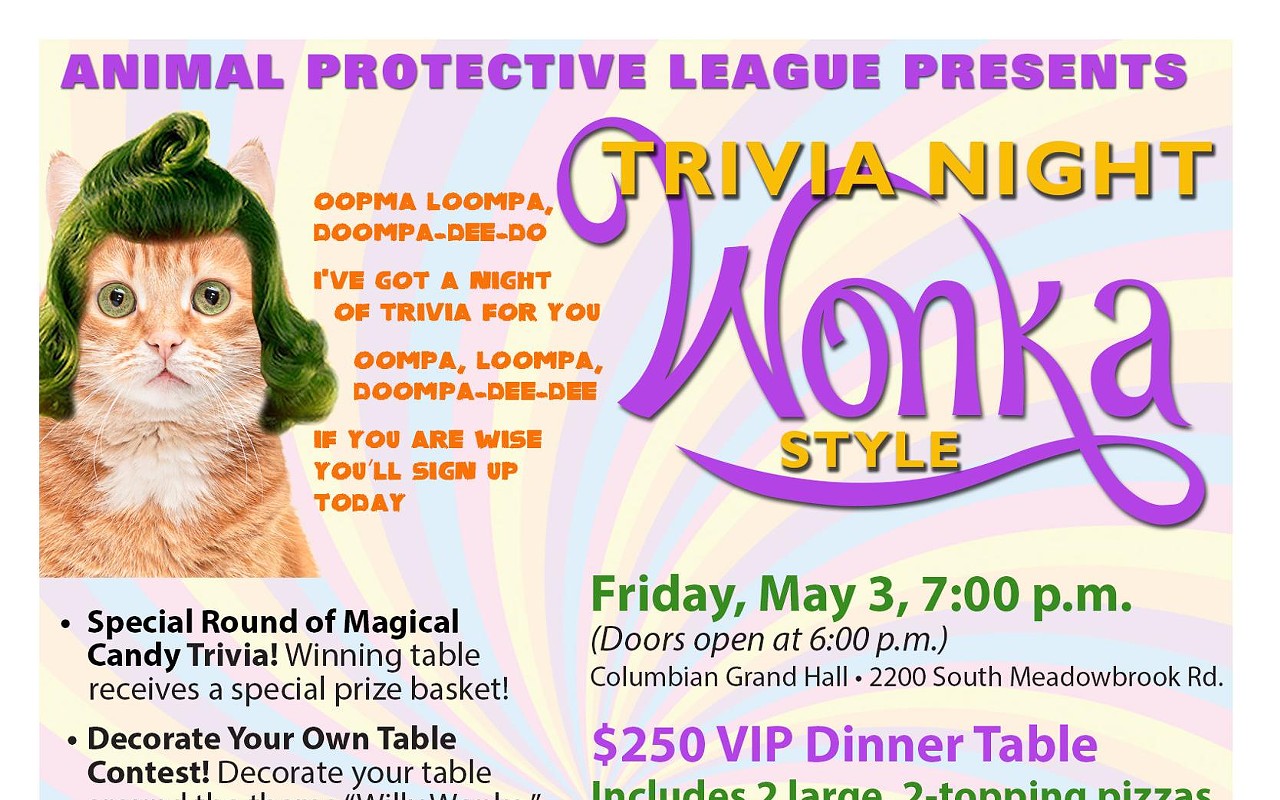

Not everyone will feel cheated by a volume that doesn't dwell on such aspects of the lake's past. This one offers the pleasures of the family album if your parents kept better notes. The book is divided into seven sections devoted to images of housing, fun stuff, the power plant and so on, each introduced with a brief scene-setting essay. Some readers will miss an index and a high-quality map of the present lake to orient those not intimately familiar with the geography of the area, but the prose is clear, the images are ample. Mazrim contributes many originals in color and Mann retrieved historic images from the riches of the Aladdin's cave that is the SVC.

The drawbacks of pictorial histories are pretty plain. What can't be shown is not talked about, and the reader will find little beyond the barest mention of the remarkable Spaulding brothers or the woeful stewardship of the lake and environs by Springfield city councils – although they do acknowledge the racism that once informed policies toward public recreational facilities.

It is only a minor criticism to note that the authors' subtitle suggests a work of grander scope. Each of the events and places and issues described in dozens of these images could sustain a chapter in the full-length narrative history that needs to be written about the lake and the experiment in municipal socialism that spawned it. Perhaps it will inspire someone to write it.

Lake Springfield is a reminder of what well-thought-out public infrastructure investments by farsighted governments can mean to a city. The decades-long dithering over Lake Springfield II suggests that the city of Springfield could never pull off a similar undertaking. That should make readers all the more grateful that it managed to do it once.

City Water, Light & Power is unusual in its commitment to keeping and sharing its own history; see https://www.cwlp.com/Images/CWLPHistory/Lake75PampForWeb.pdf. James Krohe has written often about Lake Springfield; see "Lake Springfield etc." at https://www.jameskrohejr.com/springfield-nature-environment.