The influenza outbreak of 1918 brought the nation to a standstill, and the Springfield area was not immune.

One hundred two years ago, the United States was swept into a global influenza epidemic that was called "one of the worst natural disasters in history." As many as 50 million people died around the world, while 675,000 Americans were also lost, many from related complications like pneumonia.

A quarter of the U.S. population had fallen ill by late October 1918 with what was commonly called the "Spanish influenza" or sometimes "the grip." The estimated death toll in Illinois was 22,500.

The first flu case was reported at Fort Riley, Kansas, on March 4, 1918, and it spread with lightning speed. Within a week, 500 soldiers were hospitalized. American soldiers heading overseas for World War I carried the virus to Europe, while others brought it back home as the outbreak ripped through the nation that fall.

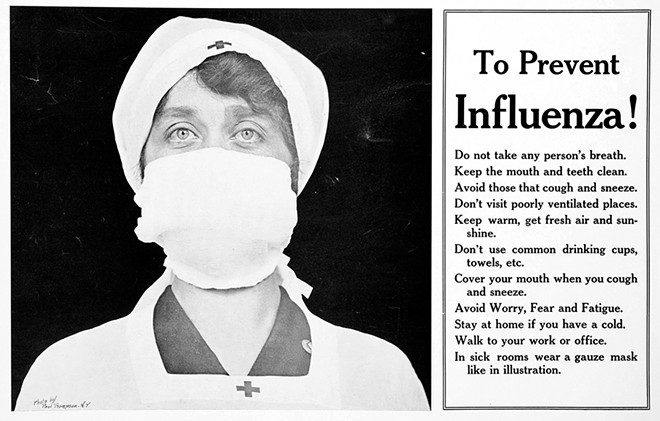

It was an era before antibiotics, vaccines, preventive care and proper sanitation and diet. Though most in Illinois were expecting the onslaught, there was little anyone could do about it.

Schools, theaters and even pool halls were shut down in Springfield on Oct. 15, and lodges and clubs were ordered to cancel meetings. The next day, the Illinois State Register ominously reported "the lid went on Springfield with a bang yesterday when health authorities closed all the schools and all the theaters...until further orders."

The paper added that "the order applies to all places of amusement...and so stringent is to be the enforcement of it that people are not to be permitted to congregate in the streets." Similar notices were also issued in Jacksonville, Carlinville, Waverly and many other locales.

On Nov. 5, some 5,548 residents of Springfield – which then had a population of 61,120 – were sick. Many communities had percentages even higher than Springfield's 9%.

There were 125 new cases in the city on Oct. 24 alone. One health inspector found one home with 10 family members stricken with influenza.

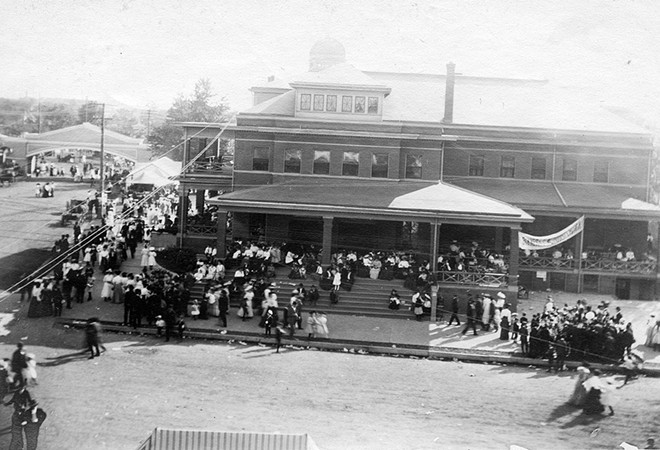

Some residents in the capital city resorted to wearing necklaces of smelly spice concoctions to try to stave off germs. A 100-bed hospital was set up at the Woman's Building at the Illinois State Fairgrounds to handle the overflow of sick patients.

A total of 398 influenza deaths were reported in Springfield in the closing weeks of 1918. The number of burials at Oak Ridge Cemetery in October and November was two and a half times higher than average, forcing gravediggers to work seven days a week.

Pneumonia was a common side effect, and proved deadly for many flu victims. The specter of pneumonia terrified the locals in Springfield, and visits to those suffering from pneumonia were banned.

In many cases, Springfield undertakers refused to enter the homes of dead pneumonia patients. One resident recalled that the undertakers, when visiting the home of a deceased flu victim, "raised the window and shoved a board in...and the people inside would wrap the body in a sheet and lay it on that board and they would slide it out."

Funerals in Springfield were limited to private services on front porches. Restrictions on honoring the dead were also placed in Chicago and Peoria.

The numbers around the area were equally mind-numbing. There were a reported 1,027 influenza cases on Nov. 5 in Jacksonville, which then had a population of 15,481. Thirty-seven residents had already died, and the numbers only kept rising.

In Bloomington, the clubhouse of the local country club and a fraternity house at Illinois Wesleyan University became makeshift hospitals. An estimated 750 of the city's 4,000 public school students were believed to be sick on Oct. 10.

Influenza became front-page news in many area papers, sharing space with reports of American troops in the war and even the armistice on Nov. 11.

On Oct. 28, a front-page headline in the Illinoian Star in Beardstown blared that over 500 Cass County residents were ill, including 100-125 in Virginia. Even Chandlerville was hit hard, with an estimated 70-80 cases.

A notice in the Star on Dec. 13 urged, "Red Cross wants men and women nurses for influenza patients. Wages will be paid. Apply at headquarters" on Second Street in Beardstown.

In Mount Sterling on Nov. 20, an article on page one of the Democrat-Message reported "more than 150 flu cases" in the town. A visiting physician from the public health department in Springfield, though, said that 150 "would be a low estimate."

The paper added that "it would be impossible to print a full and complete list of the people of the city who are victims of the disease."

In the next column was an article entitled "Spanish Influenza and How to Treat It," while the front page also ran a detailed list of recommendations to avoid the spread. Among them were "avoid expectorating in public places and see that others do the same." Carlinville passed an ordinance against public spitting during the outbreak. Still, the city reported an eye-popping 1,362 cases of influenza on Nov. 5.

Unlike other illnesses, a disproportionate number of victims in 1918 were younger people. One was Zelia Frank, a Virden native who lived in Shipman. Zelia died at 10 p.m. on Oct. 23 "of pneumonia after a short illness." Described as "an affectionate daughter and sister," she was seven weeks past her 29th birthday.

Newspapers printed lists of flu victims in Springfield nearly every day. One of the deceased in the Oct. 21 issue of the Illinois State Journal was Miss Clara Louise Kramp of East Cook Street, who was a mere 18 years old.

In Beardstown, the Star introduced a new column, "With the Sick," which carried updates on locals stricken with the flu. The Nov. 13 edition listed seven residents, many of whom were "confined" to their homes.

Many listed as American casualties in the war died from influenza in military camps. An entire column of one issue of the Macoupin County Enquirer in Carlinville was filled with obituaries of local boys who had died in camp.

Among them was 24-year-old James Henderson of Palmyra, who died in camp in Battle Creek, Michigan, on Oct. 8. He left behind a young wife and daughter.

In South Otter Township in northern Macoupin County, George Hays received the dreaded telegram that advised of the passing of his son, Lester, who was also at Camp Taylor. The communication read, "We regret to announce that your son died at the base hospital this afternoon at 4 p.m. with pneumonia. Please wire immediately where you want the body to be sent."

Of course, there was the usual profiteering. Throughout the fall of 1918, the Star carried ads for something called Terezon, which was for "influenza and the grip."

There were also ads for Foley's Honey Tar which, claimed the ad, "everyone suffering from influenza and the grip needs now," while a Minneapolis druggist ran display ads for the "really pleasant-tasting cold water salt tablets, Salinos," designed to rid the digestive system of "poisons." But these dubious products could not help stem the tide, and there were more outbreaks to come.

Theaters in Springfield reopened on Nov. 8, with schools following three days later. Still, there were enough cases remaining that another emergency hospital, a 32-bed facility at Rutledge and Miller streets, was forced to open in December.

Additional outbreaks in late 1919 and early 1920 boosted the death totals, though not as severely. Over a century later, the influenza outbreak of 1918 remains one of the worst health crises in American history.

Tom Emery is a freelance writer and historical researcher from Carlinville. He may be reached at 217-710-8392 or [email protected].