Lincoln’s Election Day in Springfield

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

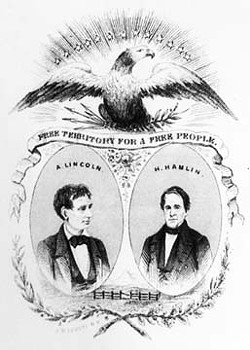

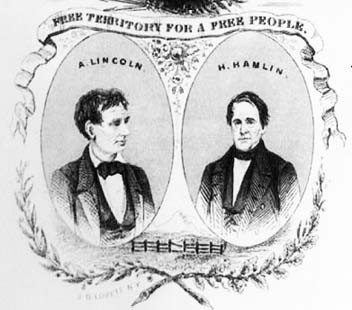

Election Day, 1860, started with a boom for Republican presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln. According to Harold Holzer’s book, Lincoln: President-Elect, local Republicans (not including Lincoln) set off a cannon in Springfield that morning to get supporters to the polls. It was a noisy day: wagons carrying loud bands roved through town as well, according to Michael Burlingame’s Abraham Lincoln: A Life.

Both likely woke Republicans from a deep sleep since most had been out late the night before parading around town with torchlights before ending up at Lincoln’s home, according to the Nov. 6, 1860, Illinois State Journal.

Lincoln had no campaigning to do that day; it would have been unseemly. “Lincoln, over the last six months, had done next to nothing publicly, and precious little privately, either in person or in print, to advance his own cause,” Holzer wrote in his book. “Prevailing political tradition called for silence from presidential candidates.”

Sage advice from peers called for it, too, according to Burlingame. In his book he quoted journalist and Lincoln supporter William Cullen Bryant who wrote to Lincoln: “I am sure that I but express the wish of the vast majority of your friends when I say that they want you to make no speeches, write no letters as a candidate, enter into no pledges, make no promises, nor even give any of those kind words which men are apt to interpret as promises.”

That morning Lincoln headed for the Statehouse (now the Old State Capitol), where he’d used the Governor’s Suite as a temporary office for the last several months, greeting politicians, well-wishers, reporters and anyone who wanted to shake his hand or talk to him. On that day, Nov. 6, a group of visitors asked him about his rail-splitting days and Lincoln demonstrated his favorite method for splitting wood.

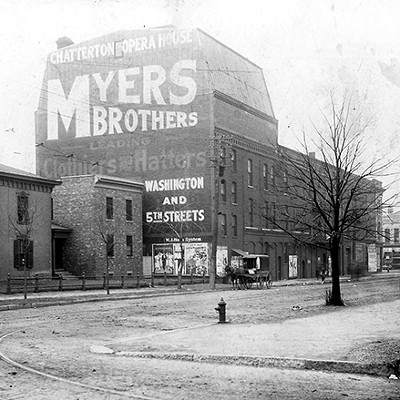

In mid-afternoon, Lincoln and some of his closest supporters headed across the street to the poll. It was at the Sangamon County Court House at the southeast corner of Sixth and Washington Streets, where JPMorgan Chase Bank sits today. Unlike now, there was no official pre-printed ballot. Instead, the political parties printed their own ballots and handed them to voters outside of the poll.

Locals nearly mobbed Lincoln as he and his friends approached the Court House. A group followed him up to the second floor, where he voted – for other Republican candidates, but not himself. According to Holzer, it was also unseemly for candidates to vote for themselves at that time, so Lincoln tore off the part of his ballot that related to presidential candidates.

After spending some more time at the Statehouse and having dinner with his family (wouldn’t that have been a dinner conversation to overhear!), Lincoln returned to the Statehouse to await returns. Local Republicans did the same, packing the Capitol and celebrating at every bit of good news.

Returns came through telegrams via the Illinois & Mississippi Telegraph Company, which was located on the second floor in the middle of the north side of the square (immediately west of the current Abraham Lincoln’s National Museum of Surveying). At nine o’clock that evening, Lincoln and a few friends went to the telegraph office to see telegrams as they came in from around the state and country.

Later, as boisterous groups gathered and cheered outside with the increasingly favorable returns for Lincoln, he and his group headed to the south side of the square, where the Republican women were holding a dinner celebration at Watson’s, an ice cream and candy store (located above what is now GianFranco’s restaurant). According to Holzer’s book, friends said Lincoln appeared calm as he chatted and joked with the crowd.

An hour later, it was back to the telegraph office to await the last returns. While local Republicans whooped and hurrahed as it became clear Lincoln had won, Lincoln seemed pleased but never elated – until he heard he had won Springfield’s vote, according to Burlingame. In his biography of Lincoln, he wrote: “When a messenger announced that he had won Springfield by sixty-nine votes, (Lincoln) abandoned his reserve and gave ‘a sudden exuberant utterance – neither a cheer nor a crow, but something partaking of the nature of each.’”

Contact Tara McClellan McAndrew at [email protected].

Both likely woke Republicans from a deep sleep since most had been out late the night before parading around town with torchlights before ending up at Lincoln’s home, according to the Nov. 6, 1860, Illinois State Journal.

Lincoln had no campaigning to do that day; it would have been unseemly. “Lincoln, over the last six months, had done next to nothing publicly, and precious little privately, either in person or in print, to advance his own cause,” Holzer wrote in his book. “Prevailing political tradition called for silence from presidential candidates.”

Sage advice from peers called for it, too, according to Burlingame. In his book he quoted journalist and Lincoln supporter William Cullen Bryant who wrote to Lincoln: “I am sure that I but express the wish of the vast majority of your friends when I say that they want you to make no speeches, write no letters as a candidate, enter into no pledges, make no promises, nor even give any of those kind words which men are apt to interpret as promises.”

That morning Lincoln headed for the Statehouse (now the Old State Capitol), where he’d used the Governor’s Suite as a temporary office for the last several months, greeting politicians, well-wishers, reporters and anyone who wanted to shake his hand or talk to him. On that day, Nov. 6, a group of visitors asked him about his rail-splitting days and Lincoln demonstrated his favorite method for splitting wood.

In mid-afternoon, Lincoln and some of his closest supporters headed across the street to the poll. It was at the Sangamon County Court House at the southeast corner of Sixth and Washington Streets, where JPMorgan Chase Bank sits today. Unlike now, there was no official pre-printed ballot. Instead, the political parties printed their own ballots and handed them to voters outside of the poll.

Locals nearly mobbed Lincoln as he and his friends approached the Court House. A group followed him up to the second floor, where he voted – for other Republican candidates, but not himself. According to Holzer, it was also unseemly for candidates to vote for themselves at that time, so Lincoln tore off the part of his ballot that related to presidential candidates.

After spending some more time at the Statehouse and having dinner with his family (wouldn’t that have been a dinner conversation to overhear!), Lincoln returned to the Statehouse to await returns. Local Republicans did the same, packing the Capitol and celebrating at every bit of good news.

Returns came through telegrams via the Illinois & Mississippi Telegraph Company, which was located on the second floor in the middle of the north side of the square (immediately west of the current Abraham Lincoln’s National Museum of Surveying). At nine o’clock that evening, Lincoln and a few friends went to the telegraph office to see telegrams as they came in from around the state and country.

Later, as boisterous groups gathered and cheered outside with the increasingly favorable returns for Lincoln, he and his group headed to the south side of the square, where the Republican women were holding a dinner celebration at Watson’s, an ice cream and candy store (located above what is now GianFranco’s restaurant). According to Holzer’s book, friends said Lincoln appeared calm as he chatted and joked with the crowd.

An hour later, it was back to the telegraph office to await the last returns. While local Republicans whooped and hurrahed as it became clear Lincoln had won, Lincoln seemed pleased but never elated – until he heard he had won Springfield’s vote, according to Burlingame. In his biography of Lincoln, he wrote: “When a messenger announced that he had won Springfield by sixty-nine votes, (Lincoln) abandoned his reserve and gave ‘a sudden exuberant utterance – neither a cheer nor a crow, but something partaking of the nature of each.’”

Contact Tara McClellan McAndrew at [email protected].

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!