Jean Broquet was having a lousy day

It was July, in Detroit, where she lived with her husband, Larry, and four daughters. The heat and humidity were oppressive. There was laundry to be ironed. The girls were screaming. She’d just washed the floors and was fighting to keep everyone from tracking in dirt. Right on time, her husband came home from work, gave her a peck on the cheek and posed an out-of-the-blue question that would change the family’s life forever.

“Hi, honey – how’d you like to move to American Samoa?”

“Great,” she responded. “Where the hell is it?”

It was 1964. Larry Broquet, a teacher who starred on a local educational television program about geography and world history, had been asked to help start up an educational television program in Samoa, where both schoolchildren and their teachers could barely speak English, Broquet’s daughter Christine recalls in an online memoir that reads like a South Pacific version of an Erma Bombeck tale. The chance that came courtesy of the federal government was irresistible for a geography teacher who couldn’t afford to take his family on vacations more than a hundred miles or so from their home.

The commitment would last two years. Research about their home-to-be was accomplished with National Geographic magazines and Tales of the South Pacific by James Michener, which Kathy, the eldest daughter who was then 12, brought to the dinner table one night.

“There’s a story in here about a man who had a disease called filariasis,” Kathy announced. “It says his scrotum weighed over 70 pounds and he had to carry it around in a wheelbarrow. Daddy, will we get filariasis? Where’s my scrotum?”

All eyes turned to Larry, “who had gone even paler than the man with the wheelbarrow,” Christine recalls in the memoir called The Samoan Letters: The Real Life Adventures of a Clueless Family in Paradise.

The government paid for the move, and so belongings that included a piano and the family’s washing machine were packed into a wooden crate. They stepped off the plane into a downpour that couldn’t wash away humidity and the stench of the sea.

“I hope to God they sell deodorant here,” Jean Broquet told her husband and brood.

The jet-lagged family wondered what they had gotten themselves into – two years seemed a very long time. After clearing customs, they were stunned by a large crowd that put leis over the girls’ necks and shouted “Talofa!” which means “Welcome.” It was traditional, they were told, to greet new teachers at the airport. Everyone got hugs. Champagne was offered. And the Broquets, who hadn’t slept in 24 hours, were whisked to a nearby village for a fiafa, a Polynesian term for party.

A suckling pig had been roasted over hot rocks. There was taro and coconut milk as well as fried chicken and potato salad and baked beans for tastes that ran Midwestern. Chickens and dogs scampered about, and the youngest daughter, Karen, a somewhat shy girl, ended up face-to-breast with a topless woman who was feeding an infant. Karen ran.

The family acclimated to, if not always copied, local customs in a place where prisoners at the local jail bummed cigarettes through windows that opened to the free world. Ants and flying cockroaches were common, and the girls learned about lice firsthand. They once fled to high ground along with neighbors to avoid a predicted tsunami that never arrived and hunkered down in a bathtub during a cyclone that proved the real deal. Larry got a driver’s license after passing a written test that included such true-or-false queries as, “It is dangerous to throw rocks at passing vehicles because innocent people might be killed or injured,” “You should not take anyone else’s car without their permission” and “You should not drive after five beers.” Larry was required to have his car inspected before being issued license plates.

“A 300-pound Samoan stares intently at the car for a few minutes, looks under the hood (after you show him how to open it), then gravely announced ‘That’s a Datsun, isn’t it?’” Larry wrote in a letter home to relatives. “That completes the inspection.”

Parties were thrown for the flimsiest of reasons – Pearl Harbor Day was marked by a bash called A Salute to World War II. In lieu of a Christmas tree, the family decorated a piece of driftwood. Their piano, washing machine and other household goods finally arrived on Christmas Eve, more than three months after the Broquets had started their tropical adventure.

School truly was thousands of miles away from parochial schools the girls had known. Christine recalls an afternoon in the fourth grade at a school near the harbor. The entire class was mesmerized by a rat that had tried scampering, tightrope-walker style, onto a cruise ship via a thick rope that tied the ship to a dock. Unable to complete the journey, the rodent turned around, and when it jumped safely back to shore, the students erupted in applause.

“Well, I can’t compete with that,” the teacher said. “Let’s have recess.”

Jean got a job at a library. Larry developed an affinity for community theater and wrote three shows, one called A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To Samoa, and gave his daughters roles in each one. As the end of his two-year assignment neared, Larry sat his family down at the dining room table: How would everyone feel about spending an additional year in Samoa? Karen, now associate dean for graduate medical education at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, abstained, but the vote was otherwise unanimous. The family signed on for another year. And then another, finally moving back to the United States in 1968. But after four years in the South Pacific, things would never be the same as before.

After four years at a public television station in West Virginia, Larry and his family moved to Springfield, where he started work in 1972 as an administrator for the Illinois State Board of Education. He retired in 1989 and traveled to Alaska, China, Europe, Asia, Africa, New Zealand and, of course, Samoa, which was one the first overseas destinations after retirement. He tried to become a contestant on “Jeopardy!,” his favorite television program, and settled for an appearance on “Who Wants To Be A Millionaire.” He won no money.

Larry was always proud of his work creating educational TV programs for Samoan schoolchildren, Karen says, and he brought a bit of the island territory to Springfield, where he often wore a lavalava, a piece of cloth worn around the waist, when relaxing at home.

“Friends would come over and ask ‘Why is your dad walking around in a skirt?’” recalls Christine.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].

Illinois Times gratefully acknowledges Christine Broquet’s online memoir from which much of the information and quotes in this story came. Read it at https://thesamoanletters.wordpress.com/index-3/

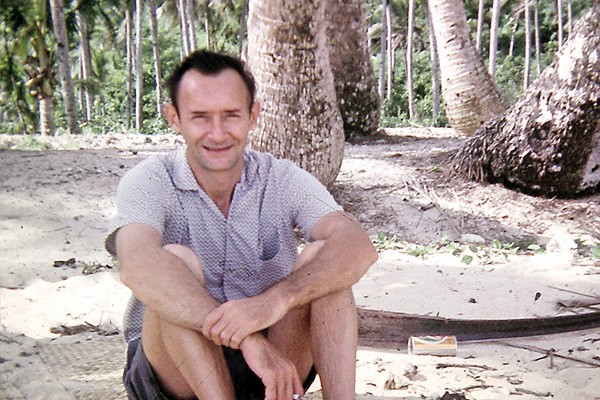

Life in paradise

LAWRENCE A. BROQUET March 25, 1927-Nov. 28, 2016

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!