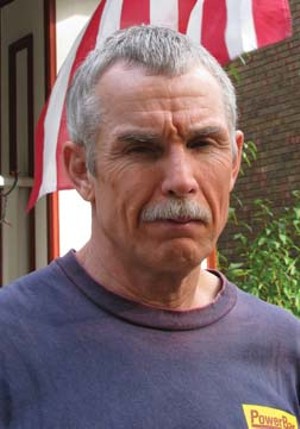

William “Bill” Shea’s wheelchair sits in the corner of his basement. It is both a reminder of the past and a foreshadowing of the future. At 59, Shea embodies the qualities of an Olympian. He is physically fit, resilient and determined. This has not always been the case.

As a child, Shea struggled with respiratory ailments, undiagnosed dyslexia and a difficult home environment before finding an outlet in sports. As he grew into adulthood, Shea played football and rugby, participated in boxing and martial arts, and trained for the Olympics in the 400M sprint. As an elite runner, he participated in more marathons and ultra-marathons than he can count.

Along the way, he overcame his learning disabilities to earn an interdisciplinary studies degree from Old Dominion University and a master’s degree in history from National University. When he wasn’t in school or training, Shea worked on archeological digs, served as an interpreter for the National Park Service and joined the Navy.

While serving in the Navy, Shea heard that Olympic bobsled teams were recruiting military personnel. Still carrying his dream of participating in the Olympics, he immediately took and passed the physical. Moving to Lake Placid, N.Y., he trained on what were, at the time, the most treacherous competitive bobsled runs in the world.

In the winter of 1987, while on a training run, the bobsled Shea was riding crashed. Shea estimates that the sled was traveling nearly 100 miles an hour and pulling about 4-g’s when it went too high on a curve called Big Shady, hitting the curve’s lip, sliding down into the trough and becoming airborne. When the sled hit the run again, Shea took the brunt of the impact. While everyone else walked away from the accident, he was hospitalized with a skull fracture and traumatic brain injury.

Unable to afford hip replacement surgery and unwilling to quit participating in sports, Shea took up wheelchair sports. When his arthritic knees and hips would not allow him to sit in the tucked position required for wheelchair sports, Shea took up hand cycling, setting a record at the 1998 LaSalle Banks Chicago Marathon and becoming one of the first hand cyclists to participate in the Boston Marathon. As a member of the U.S. Hand Cycle Olympic team, he participated in races all over the world.

Eventually, Shea had the hip and knee surgeries that allowed him to leave his wheelchair. While he knows that his arthritis may someday force him back into the wheelchair, Shea follows a disciplined daily regiment of physical fitness and martial arts training to help maintain mobility. He is currently developing an adaptive martial arts program to help other people with disabilities meet their maximum physical potential.

In spite of an impressive list of physical accomplishments, and several years working with a local psychologist to improve social skills, Shea continues to struggle to become an integrated part of his community. Contending that he has an injury similar to amputation, he has tried to educate his neighbors and local authorities about his brain injury. However, he finds that others have difficulty understanding the differences between his brain injury and mental illness.

After more than 20 years of living with a brain injury, Shea believes that without holistic approaches to rehabilitation and reintegration, he and thousands of other Americans with brain injuries, some of them veterans returning from the wars in the Middle East, will continue to live in a no-man’s land, struggling to become valuable, respected members of their communities.

Contact Grace at [email protected].