Just when we thought Rwanda had reinvented itself into a genuine success story in Africa, and that Rwandan president Paul Kagame had become a star of international leadership, along comes the hero of Hotel Rwanda to tell us it isn’t necessarily so.

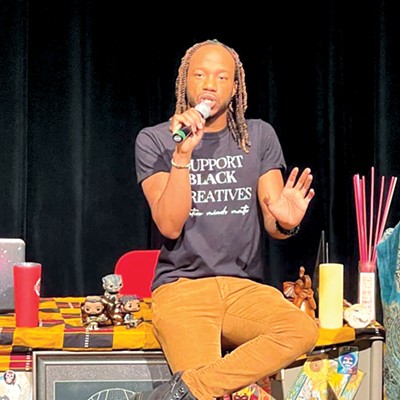

Paul Rusesabagina, portrayed in the 2004 film Hotel Rwanda by actor Don Cheadle, speaks in Springfield 7:30 a.m. Wednesday, May 12, at the Governor’s Prayer Breakfast at the Crowne Plaza Hotel. Rusesabagina is disillusioned with Kagame, who led rebel forces that ended the 1994 Rwanda genocide. Kagame has been president since 2000 and faces reelection in August. He is widely credited not only with restoring order in Rwanda, but also with revitalizing the nation’s economy.

But Rusesabagina has been spreading the message that Rwanda’s gains have come at the price of freedom, and that unless the international community somehow curbs Kagame’s increasingly repressive ways and brings out the full story of the genocide, Rwanda’s success could come undone. In a telephone interview with Illinois Times from his home in Brussels, Belgium, Rusesabagina said he will ask his Springfield audience to partner with him in his effort to bring out the truth about the genocide. “So far, no one talks about the truth in Rwanda,” he says. “They talk about unity and reconciliation. But people should never unite without the truth.”

Because of the film, many know the story of how Rusesabagina, serving as manager of the Hotel des Mille Collines (thousand hills) in Kigali, risked his life to shelter Hutus and Tutsis who came there seeking refuge from the genocide that killed more than 800,000 people in a period of 100 days.

“What you may not know,” he says in a video on his foundation’s website, “is that the ethnic conflict which led to this genocide has still not been resolved. The ethnic conflict has spread to the Democratic Republic of Congo, where more than 5 million people have died. The exploitation of the Congo’s ‘conflict minerals’ by Rwanda is fueling this horrible war. Poverty, inequality, discrimination and political repression are on the rise in Rwanda. We have a moral responsibility to change this.”

Just last week the New York Times took note of Rwanda’s increasingly repressive regime in a front page article on “rehabilitation camps,” where young adults are sent for petty crimes without trial. “While the nation continues to be praised as a darling of the foreign aid world and something of a central African utopia,” the newspaper said, “it is increasingly intolerant of political dissent, or sometimes even dialogue, and bubbling with bottled-up tensions.”

Some of the tension results from anticipation of the August elections. So far Kagame has not allowed leaders of opposition parties to register to appear on the ballot to oppose him. Some of the detractors of Kagame, a Tutsi, contend that thousands of the victims of the 1994 genocide were actually Hutus, though the general conception is that Tutsis were the victims. A “genocide ideology law” passed in 2008 makes it illegal to speak of the genocide in certain ways.

In the interview, Rusesabagina said Kagame’s popularity on the world stage is fading because of his increasing hard line against opponents. He said three of Rwanda’s high-ranking generals have been arrested and jailed, while two more have been sent into exile. He said the Human Rights Watch representative was kicked out of Rwanda on April 24. Last month the government shut down two independent newspapers because of opposition to Kagame, he said.

Rusesabagina wants an international “truth and reconciliation commission” set up to investigate what really happened during the genocide and what has happened since, including Rwandan involvement in the ongoing war in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo. He contends that, although Rwanda has no mineral wealth of its own, “conflict minerals” taken from Congo are now its top export.

I asked Rusesabagina if he would consider returning to Rwanda to run for president. “As a humanitarian, I have to remain neutral,” he said. I noted that he didn’t sound neutral to me. He answered, “I cannot remain silent.”

Fletcher Farrar stayed at the Hotel des Mille Collines when he visited Rwanda in 2008. For more information on Rusesabagina’s current activities, go to hrrfoundation.org.

The Governor’s Prayer Breakfast, featuring Paul Rusesabagina, is 7:30 a.m. May 12 at the Crowne Plaza Hotel in Springfield. For tickets contact Paula Luebbert or Sharon Caldwell ([email protected]) at Lincoln Land Community College Capital City Training Center, 130 W. Mason, Springfield. 217-782-7436. Those interested in going are advised to call today as ticket sales will be closed this week and will not be available at the door.