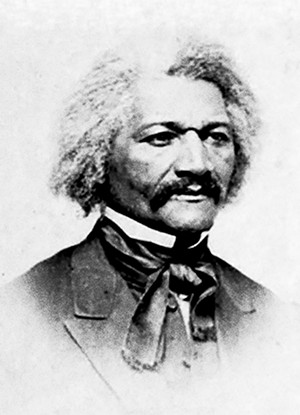

On April 3 and 4, 1866 – 144 years ago this month — Springfield was visited by one of the greatest orators of the 19th century and the best-known, and most photographed, civil rights activist in the world. Born a slave in Maryland in 1818, Frederick Douglass learned to read and write, and emancipated himself at the age of 20. He was a fugitive slave for several years living in New England and Europe, during which time the nation wrestled with the Missouri Compromise, the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Dred Scott Decision. His freedom purchased by friends in England, Douglass came home to become a leading voice for black emancipation, standing alongside such abolitionists as William Lloyd Garrison, Henry Ward Beecher, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and John Brown to help overthrow oppressive black laws and the slave powers in the South.

A man of words, Douglass edited his own newspaper for 16 years, wrote and rewrote his best-selling autobiography three times, penned fiction and poetry, but made his living later in life with his voice. During the Civil War he visited Abraham Lincoln in the White House and, before the election of 1864, helped Lincoln craft a plan whereby the federal government and the Union army could liberate slaves in the South, should the election be lost and black emancipation be nullified by a new president. It wasn't necessary. Lincoln won the election, the 13th Amendment was passed and Reconstruction held out the promise of civil rights and possible suffrage for African American males.

But in the 12 months that followed, Lincoln was assassinated, Andrew Johnson became president and a new slavocracy, comprised of plantation owners and former Confederate soldiers, reasserted its influence in Congress, fueling states' rights advocates to find ways to impose new black laws. On Feb. 7, 1866, Douglass and 13 other black activists, took their concerns to the White House and compelled a reluctant President Johnson to listen to their issues, especially concerning black suffrage, which Lincoln had advocated in his last public speech. Johnson, who "no more expected that darkey delegation... than he did the cholera," rejected Douglass' impassioned plea for black suffrage and told the delegation that "colonization was the best option" for freed-people, and that black suffrage would lead inevitably to race war. Douglass argued that without suffrage, war is exactly what the nation might expect.

Soon after this confrontational White House meeting, Douglass began a grueling spring lecture tour. The following week (Feb. 13) he was booked by the Springfield Library Association to speak in the capital city, but spring floods washed out a bridge on the Illinois River Railway, delaying the program for a week. That program, too, was canceled due to bad weather and rescheduled for the first week of April, the month of the first anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's assassination. Douglass arrived with two programs, each delivered on consecutive evenings in the Statehouse – what we call the Old State Capitol. The first was titled "The Assassination and its Consequences," and the second was on the topic of "Reconstruction." On April 3, Douglass was introduced by then Gov. Richard Oglesby, who himself had been visiting with Lincoln on the afternoon of the assassination and was with the dying president at his bedside. What follows is a portion of that lecture, as printed in the April 4, 1866, edition of the Illinois State Journal, and in Douglass' handwritten notes on the lecture penned in December of 1865.

"Had Abraham Lincoln died from any of the numerous ills that flesh is heir to, and by which men are ordinarily removed from the busy scenes of life; had he reached that good old age of which his excellent constitution and his equally excellent temperate habits gave promise; had the curtains of death fallen gradually round him, we should have followed him sadly enough to his honored grave, placing him side by side with our most honored dead, but without any special distinction, and without the manifestation of those unusual signs of national bereavement for which his funeral will be ever memorable.

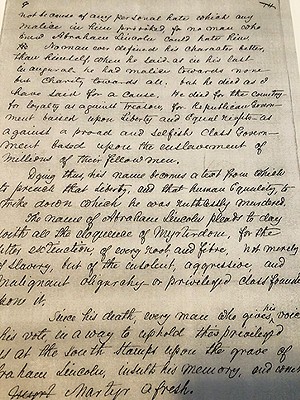

"But dying as his did die, for a cause that takes hold of human nature; dying as he did die, by the red hand of violence; dying as he did die, at the moment when evincing his greatest trust in the people – going among them freely like a common man without a guard when he was commander in chief of millions of armed men – snatched suddenly away from his work without warning – killed, murder, assassinated – not because of any personal hate which any malice in him provoked, for no man who knew Abraham Lincoln could hate him. No man ever defined his character better than himself when he said, as in his last inaugural, he had 'malice towards none but charity towards all.' But he died, as I said, for a cause. He died for the country – for loyalty as against treason, for Republican Government based upon Liberty and Equal Rights as against a proud and selfish class government based upon the enslavement of millions of their fellow men."

"A new era is before us, and it may be marked with features darker and more calamitous than assassination and rebellion. Our national honor is in peril. The danger impending over us is the cold, cruel, wanton surrender and betrayal of our friends and allies – the only friends and allies that the South gave us as a nation. As a nation, then, we ought to be instructed, if judgments heavy and terrible can do it.

"Yet soon we forgot the lessons of war, and treason and rebellion were already beginning to be thought of as slight offenses; a feeling of blind charity filled our hearts. Did this magnanimity soften the iron hand of slavery, or purify the heart of treason? No. It did not then; it does not now, and nothing but the stern hand of justice ever will. They seized the moment when we were weary of war, inclined to mercy, to deal upon the nation the heaviest blow it had yet received at their hands. We mourned Abraham Lincoln, not so much because the country had lost a president, but because the world had lost a man, one of the very best men that presided over the destinies of a nation.

"The life of Lincoln was one of devotion to principle, and was crowned with success. At the time of his death, slavery was abolished, and liberty established; and he who today argues in behalf of slavery or any of its horrid pretentions, stamps upon the grave of Lincoln."

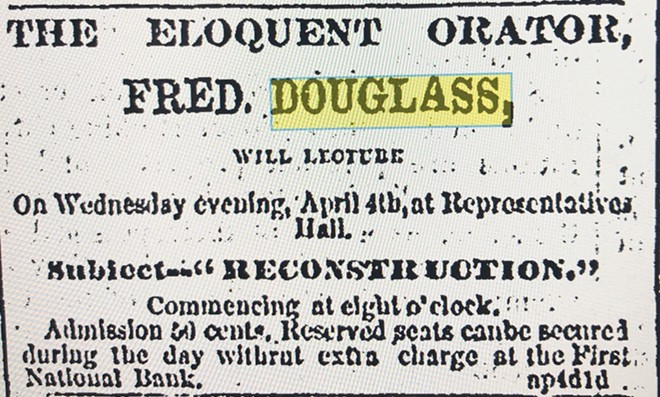

The next evening, on April 4, 1866, Douglass returned to the Statehouse to deliver his lecture on Reconstruction. James R. Doolittle, whom Douglass refers to in his lecture, was a moderate Republican senator from Wisconsin, who after the war, did his best to backpedal emancipation by pledging to give states the right to decide for themselves on matters of civil rights and suffrage for blacks, an issue later addressed by the 14th and 15th amendments. In this transcription of Douglass' speech, as published in the April 5 edition of the Illinois State Journal, Douglass takes Doolittle to task for living up to his name.

Illinois State Journal: The weather was extremely disagreeable last evening. It rained without cessation; was dark, muddy, and generally unpleasant. Notwithstanding this, quite a large audience gathered in Representative Hall to listen to the lecture of Fred. Douglass upon "Reconstruction." Quite a number of those present were ladies, yet the larger proportion were men. There are few lecturers that could have drawn such a house on such a night. The entrance of Mr. Douglass into the Hall was greeted with applause, and when he arose to speak, another round of applause was given. He began by saying that the crisis now upon our country was fully equal to that day when a million men sprang to arms to defend the nation.

Quoting or paraphrasing Douglass: "In war we had the prestige of power and government; but some traitors and treason abettors have no fear of prison or punishment. [Clement Laird] Vallandigham and men of that stamp in league with rebels, can now again speak their villainous sentiments. It seems that we have gone back to the days before the war. It only seems, for we made progress during the war. The cause of liberty was advanced. The work of an age was done in a day. A change is now upon us.

"The President [Andrew Johnson] has placed himself on the side of the slave power. Slavery is dead, but the sentiments it created still live. The President aims at the union of defeated rebels with the Copperheads of the North, in order that they may again crack their whips over the loyal men of the North. Will this plan succeed? I think not. The civil rights bill will be passed. Johnson has shown the cloven foot too soon. Had he concealed his designs longer he might have been successful. His administration began with an "experiment," soon to be abandoned for out and out treachery to his party. His veto of the [Freedman] Bureau Bill first disclosed his policy, and the return of the Civil Rights bill showed exactly where he stood. He is the champion of the South.

"We are betrayed, but we are not ruined. Our nation is strong and great – great in power, brain, heart, education, morality. It survived years of war, of trouble, of blood; it survived [Major General Fitz John] Porter and the Little Napoleon [General George B. McClellan], and it will survive Johnson. However, Johnson is a strong-willed, unscrupulous, impetuous, fiery-tempered man, and can be controlled by no one. He is dangerous, and may yet plant his cannon in Washington, and dismiss Congress, to place in the Capitol traitors and Copperheads.

"The right to liberty is co-extensive with the love of liberty. This is the American doctrine, proclaimed in 1776, and will yet become the rule and law of the land. In this is the secret of Reconstruction. The war has settled that our Union can never by any means be destroyed. It cannot be broken up – nothing can triumph over it. Neither can the Union be maintained half slave and half free – there must be common sentiments and common aspirations, and all persons must stand secure in the broad basis of equal rights before the law.

"It has been settled that the negro will work, will fight, will die, if need be, for truth and freedom. He is a necessary element of the South; as a producer he cannot be dispensed with. He must remain in the country. Some want him removed, and insist upon keeping the negro degraded in every particular. Among these is Mr. [James Rood] Doolittle. How appropriately some men are named. The negro is capable of civilization, and readily adapts himself to the circumstances by which he is surrounded. The race has withstood all the exterminating influences of slavery for 250 years, and yet is strong and ready to advance in the scale of intellectual and moral progress. In all latitudes and climates he is the same – enduring and true, and waiting for improvement. In war and peace he is a reserving power for the good of the nation. He is here. Shall he be a blessing and an honor, or a curse and a disgrace to the country? This is the question of reconstruction."

"The other issues are of minor importance, and time will prove the truth of these words. The negro should be allowed to vote. The Caucasian race is too strong to be hurt if the negro does vote. He should do so because he is a man. He has helped to bear the burden of the State, and should receive the privileges of the State. He is a citizen and only ceases to be such when his rights are withheld from him. He wants the ballot as an educator, to protect him in his rights as a man and a citizen, because he deserves well of his country. He has been the nation's friend in the dark hour of war, and in these days of peace. I have seen white copperheads and blue copperheads, but I have never seen a black copperhead.

Illinois State Journal: "The speaker here rehearsed the services of the black man during the war, and was applauded at the close of every sentence. He should vote because he may be wanted again in the defense of the nation. The Southern Cause at last wanted the negro, and its last howl was, 'Help, Pompey, or I sink.' We may in 10 days have foreign war, and then the negro will be wanted again. Give him a trust, and he will ever be worthy of being trusted. England has ground her heel into the heart of old Ireland, and she is in danger. Let us be warned. The Federal Government is hated in the South, and as its men go there they need friends. Let the negro vote and he will be that friend. He should vote because of the universal law of the country. National honor requires that he be enfranchised. The nation owes the negro a debt of honor, which must be met if we would be just. We have proclaimed the freedom of the negro; to maintain it we must let him vote. The race is called inferior. This may be; but had he his rights, he would soon be a better man. There would be no "war of races," for it would make the white man the black man's friend, if the latter wielded the ballot.

Illinois State Journal: "Here followed an eloquent appeal in behalf of the colored race, and it was stated that as long as the nation is false to that race, reconstruction cannot be successfully accomplished.

The newspaper continued: "He then alluded to Andy Johnson and his policy. Jeff. Davis was a great traitor. He was a wolf, but not a wolf in sheep's clothing. He was true to those who trusted him with power. He did not put himself as the head of the rebel cause to betray it, as Johnson has done to the loyal cause. He [Johnson] would sell us gladly to the rebels if he could, but we have him where he can do no harm. If he persists in trying to carry out his schemes, it were better for him that a mill stone were hanged about his neck, and he cast into the sea. Such men as Yates, Sumner, Stevens, Chase, Grant, and men of that class, will yet bring us out of this trouble. Let us believe in them and trust them, and all will be well. Mr. Douglass closed by simply asking that justice, simple justice, be done to the negro.

"The lecture was altogether an earnest appeal in behalf of a down-trodden race, and though many present could not endorse all that was said, they felt that the speaker understood the true nature of our present trouble of Reconstruction."

After his two lectures in Springfield, Douglass's lecture series then took him to Bloomington, where he spoke on April 5, and from there on to Galesburg and Ottawa, where it is believed he spoke the following week and had his photo taken. From Illinois Douglass traveled to Dubuque, Iowa, and Madison, Wisconsin, where he also lectured [his lecture fee was $100 per night]. Douglass was back in Washington, D.C., in time for the passage of the Freedmen's Bureau Bill, and the passage of the 14th amendment on June 13, 1866, by the U.S. House, which provided that all (male) citizens born or naturalized in the United States are entitled to equal protection under the law.

Compiled and edited by William Furry, executive director of the Illinois State Historical Society and editor of Illinois Times from 1997-2001.