Every week, Amy Alkon provides IT readers with her spin on romantic problems in her syndicated column The Advice Goddess. The column, which received the first place award for commentary last month from the LA Press Club, can sometimes be as much a sounding board for Alkon’s brassy personality as a forum for practical advice and it’s safe to say that nobody is likely to mistake Amy for standard advice bearers such as Dear Abby or Ann Landers. She sometimes comes off as ferocious and opinionated, with an occasionally abrasive sense of humor that can leave readers smarting. Although her work appears throughout the country in more than 100 alternative weekly papers, those bastions of liberalism, Alkon’s approach can sometimes be surprisingly traditional: She tends to favor standard gender roles, for instance, and often evinces a “tough love” approach to dispensing her advice.

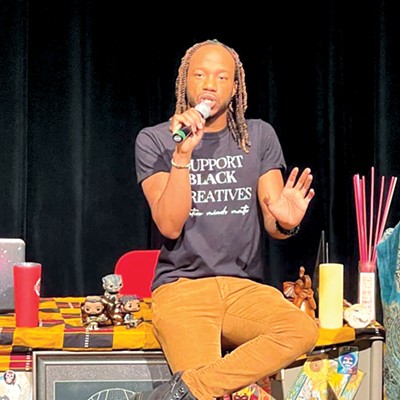

In November of last year, Alkon, who was born in 1964, published her first book, I See Rude People: One Woman’s Battle to Beat Some Manners Into Impolite Society (McGraw-Hill, 2009). As the title suggests, the book takes the form of a crusade against all types of rude behavior, from people who talk loudly on cell phones in public to parents who allow their children to run rampant. Typically for Alkon, she is not content to simply describe examples of the problem: the book is brimming with scientifically-based theories explaining why she thinks rudeness prevails in the first place as well as step-by-step instructions on exactly how readers can fight back against the rude people they encounter. In one particularly riveting section, Alkon describes how, when the LAPD failed to apprehend the thief who stole her car (a pink 1966 Rambler), she took the matter into her own hands and through a combination of persistence and coincidence managed to track down the thief herself.

We recently cornered Amy and asked her to answer a few questions about herself for a change – and in the process discovered what happens when an Advice Goddess turns her gaze inward.

Dear Amy,

What rock did you crawl out from under? How did you end up with an advice column, anyway?

—Bet I Could Do Better

I’m originally from the Midwest, from Michigan. And when I was 10, I saw this Jill Clements photo in American Girl magazine of this really stylish girl in a plaid skirt striding across a street in New York. And from that moment on, all I wanted to do was get there. I wrote for my high school newspaper, won some awards and went to University of Michigan for three years and couldn’t stand it a moment longer and bolted, went to New York, because I had a scholarship for something I wrote. And so I graduated from NYU, and then went looking for a job.

I made films in my year at NYU and I used one to get a job at an ad agency, Ogilvy-Mather, where I had these two wacky friends and we had this idea that we would set up a Free Advice booth on West Broadway and Broome, which are two streets in SoHo. We didn’t even want to charge five cents because we thought, “Who’d pay us, even a nickel?” So I made this sign: FREE ADVICE FROM A PANEL OF EXPERTS and we got chairs from a thrift store and a magazine rack and a table and set them out on a street corner, thinking that people would walk by and laugh. Well, it’s New York and the sign said “Free,” so they lined up around the block!

Now, I had no illusions that I could have any kind of career out of this free advice thing, I was just a wacky broad, as my boyfriend would say. So we’re doing this for five years and then this guy from the New York Times writes a story for the Style section about us - and, like, all hell breaks loose. Soon we’ve got a lawyer, an agent, a book deal and a column in the New York Daily News. One of my partners died, unfortunately, and the other one quit, so I ended up doing the column in the Daily News by myself, and since it was very popular in the features section, I wanted to be in more papers so I thought, “I know, I’ll get syndicated.” So I went to these syndicates and they all said “Nah, Ann Landers and Dear Abby have all the real estate in papers, you’ll never make any money.” And I thought, like, “Screw you.” And I’ve always read alternative weeklies, wherever I went, they were my favorite papers, the papers that spoke most to me. So I took some samples of my column and went to the conference for alternative weeklies that year and got into 70 papers by myself! Then the syndicates were like, “Hi! Hello! Let me court you!” and so that’s sort of how it happened.

By this time I was reading all these evolutionary psychology books like The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins, and a lot of what I do in my column is translate what’s basically ivory tower research, stuff an ordinary person would never see or read about, and put it out in my column in a way that makes a difference in ordinary people’s lives. It’s not just the opinion of the lady next door: my opinions are based in science. If I have a religion, it’s that. Where is the evidence? Look for the evidence. Is there evidence? Is there enough evidence? What are the limitations?

But nobody needs to know that when I write my day-to-day column. When I was in my 20s, I liked to use big words to impress people with my vocabulary, but now I’m happiest if I write, like, at a seventh-grade level, ’cause I want to communicate. And make people laugh.

Dear Amy,

You wrote a book about trying to stop people from being rude? Who do you think you are, Miss Manners?

—Politenessman

It’s funny that people call it “common courtesy” because I find that courtesy is becoming less and less common. And actually, I figured out why people are rude, based on the work of a British anthropologist named Robin Dunbar, who measured the human neocortex and figured out that it seems humans have a maximum group size of 150. That’s where you know them and they know you and you owe them and they owe you. And based on his work, I decided that we’re rude because we live in societies too big for our brains. We did not evolve to be around strangers, we basically have Stone Age Brains. Since we’re not used to being around strangers, we don’t really have it in us to tell the strangers, “would you mind putting a sock in it” when they’re shouting in their cellphone at the drugstore. You just want to think your thoughts. At one point in the book, I ask someone, “Why do you think our attention belongs to you?”

The point I want to make is that people who are rude are actually stealing from us but we don’t see it that way. If somebody takes your wallet, it’s there and then it’s gone, it’s a tangible thing that has disappeared from your life. But what people who are rude are doing is stealing your time, your peace of mind, your good night’s sleep. And so we need to see that as theft just as we do with a stolen wallet and tell these people, “Hey, you can’t victimize me.”

There was an episode in the café where I wrote my book. This woman sits down behind me at 8 o’clock in the morning and starts belting out her call like six inches from my head. And they actually have a No Cell Phone policy in this place so I mention it to her and she’s like “You’re interrupting my call.” Uhhh, you’re interrupting my life. And so I made this comment to her, “You know, my time is very valuable to me and you took 30 seconds of my attention.” She said, “Fine, I’ll give you a dollar.” Well, I was dressed kind of nicely, so I think she thought I’d turn down her offer of filthy lucre, but I said “Cool! Because if you pay me, you’re not abusing me, you’re employing me. Hey, 120 dollars an hour isn’t a bad rate, I’ll go for that.”

There are two ways to deal with this kind of rudeness. I’m what’s called a “costly punisher,” which is a term from economics, and it means, basically, you have a strong sense of justice and when you come upon injustice you take steps against it at cost to yourself and at no benefit. So if I ask somebody to pipe down at a café they could shout at me or punch me in the nose or shoot me. I’m not gonna win the lottery because I confront them. But most people just feel really uncomfortable saying anything and I understand that. Another thing that we can do is make an effort to treat strangers like neighbors. Do small kindnesses for people. For instance, I always have the newspaper, I read it every day, and someone’ll walk into a café and they’ll be looking around for a paper, and so I’ll just notice them and say, “Sir, would you like my newspaper?” You’ve noticed a stranger, you’ve solved their problem, you’ve gone out of your way to do it and they’re gonna feel very good about that and I think people will tend to pass on good deeds, do other good deeds, if you do good deeds for them. But it does make a difference.

But I want to emphasize one thing: I didn’t write the book because I have perfect manners. I’m rude. We’re all rude. But what I try to do is recognize the ways that I’m bad and try to be better. I try to admit all my faults, ’cause then you can fix them and they’re out there, it’s not like they’re hidden: they’re dancing naked in front of you and you’re like, “Oh, I’m so embarrassed, I have to change that.”

Dear Amy,

Speaking of rude behavior, some of the advice in your column can come off as downright mean. These people come to you for help and you tear them apart. What’s the story?

—PeaceLove&Understanding

The column is also supposed to be funny. Frankly, I have these huge e-mail exchanges with the actual people looking for advice before it’s ever in the column. I try to make the column funny for everybody else but by the time it goes to press I’ve already answered the person’s question in private. When I answer in the column I can go more in-depth and spend three weeks reading all the studies since 1971, which I just do because it means something for me to do that. ’Cause nobody would ever know, but I would know. And that’s the thing: when you’re a jerk, well, the world might not know, but you know you’re a jerk, and it’s kind of hard to live with yourself if you know you’re a jerk.

Dear Amy,

How do we know you’re not lonely, single and just taking it out on the rest of us with this high and mighty advice you always give? Seriously: What’s your status?

—Enquiring Mind

Okay, here’s how I met my boyfriend: I was shopping at the Apple store here in LA and I saw this guy, wearing smart-boy glasses, a little disheveled, you know. And I thought he was cute so I went over and I flirted with him. And he did something not everyone would have done. Do you know what he did? He asked me out right then and there. And if he hadn’t done that he would be just a dim memory of some cute guy I met at the Apple store once. But instead, here it is eight years later, and we’ve been together that whole time.

Scott Faingold is the author of the novel Kennel Cough and former assistant music section editor for the Houston Press. He can be reached via [email protected].