When the judge read the verdict, Julie Rea Harper let out a gut-wrenching cry and collapsed. Her attorney made a futile attempt to catch her, and for a moment she sprawled on the floor. Mark Harper scrambled over the courtroom railing to reach his wife. Holding her face in his hands, he told her, “Julie, it’s over. It’s over.”

It was a dramatic ending to a tragic saga that began in the predawn hours of Oct. 13, 1997, when Julie’s 10-year-old son, Joel Kirkpatrick, was stabbed to death as he slept in their Lawrenceville home. All along, Julie insisted that she had been jolted awake by an unearthly scream, rushed to Joel’s room, and struggled with a masked intruder. But with no sign of forced entry, authorities discounted her tale and instead focused on her as the primary suspect.

Over the years, her case gained national attention as she was tried, convicted, sentenced to 65 years in prison, then set free when her conviction was overturned, only to be charged again. The spectators assembled at her second trial included not just the usual complement of family and friends but also earnest law students, college professors, activists, reporters, two network television producers, and eight sheriff’s deputies ready to quell any unseemly reaction to the verdict.

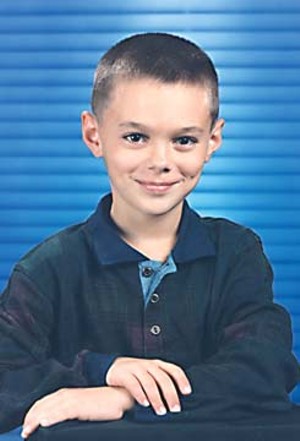

The crime demanded retribution. Joel was by all accounts an exceptional child — brilliant but sweet, both gifted and giving. The photos of his fragile corpse, gashed through the chest, transfixed jurors, causing some of them to weep. If such a depraved act had been committed by his own mother, it surely represented the most grotesque brand of evil.

But what if she was purely innocent? What if there really was a masked intruder? Wouldn’t the persecution of a loving, grief-stricken parent only compound an already heinous crime?

Ed Parkinson pursued Julie Rea Harper for more than six years. A lawyer from the Office of the State’s Attorneys Appellate Prosecutor, Parkinson had secured the original indictment in 2000 by presenting the case to a grand jury. In 2004, the Fifth District appeals court ruled that he had usurped his authority and dismissed Harper’s indictment and conviction — but by then the statute outlining SAAP powers had been expanded to allow Parkinson to prosecute the case again. Harper was released from prison only to be met at the gate by the Lawrence County sheriff, who rearrested her and took her straight to jail. This second trial, held in Clinton County last month, signaled the culmination of Parkinson’s crusade.

When word came that a verdict was imminent, Harper’s supporters had to be summoned from a nearby chapel, where they had been praying and singing hymns. Her attorneys had to drive over from their motel, where they had waited out jury deliberations by playing charades and word games. But Parkinson, who had spent the entire day waiting in the courtroom, carried some boxes out to a state police officer’s car and drove away. By the time the judge announced that the jury had found Julie Rea Harper not guilty, Parkinson had disappeared.

The second trial differed from the first in several significant ways, the most quantifiable of which was the brain power arrayed around the defense table. At this trial, instead of relying on one small-town public defender, Harper had more than a half-dozen lawyers — a veritable legal dream team.

The pack included two assistant professors from Northwestern University’s Center on Wrongful Convictions: Karen Daniel, a Harvard Law School grad who helped overturn the conviction of Randy Steidl; and Jeffrey Urdangen, who spent 23 years in private practice-criminal defense.

Harper’s lead attorney was Ron Safer, managing partner with the silk-stocking Chicago firm of Schiff Hardin and now one of the lawyers hired to handle subpoenas served to Gov. Rod Blagojevich. In the late 1990s, he was chief federal prosecutor in the criminal division of the U.S. attorney’s Chicago office, where he was known for masterminding the investigation and successful prosecutions of scores of upper-echelon Gangster Disciples drug lords.

It was the best defense money couldn’t possibly buy. Nine years of this legal battle had depleted her family’s resources. Harper’s parents, Jim and Jane Rea (a minister and a schoolteacher, respectively) had sold their property and borrowed money; her husband, a former engineer, had declared bankruptcy (and completed law school). The high-powered crew of Safer, Daniel, Urdangen, and the rest represented Harper for free.

But the most obvious difference between the first trial and the second was the fact that someone else had voluntarily confessed to the crime. Tommy Lynn Sells, a convicted killer, is housed on Texas’ death row as the result of a somewhat similar crime — sneaking into a residence in the wee hours and stabbing a young child to death. Sells claims to have murdered as many as 50 people across the country. Though a handful of his confessions have been proven false, law-enforcement officials in Texas confirmed his guilt in 15 killings and two attempted murders before Sells stopped cooperating with their investigation. Five of those crimes involved victims he stabbed as they slept.

In Joel’s case, Sells’ recall wasn’t perfect; as with other statements he had given, Sells muffed details when he began talking about the crime, some five years after it occurred.

Parkinson consistently refers to all Sells’ statements as either “garbage” or “that Tommy Lynn Sells crap.”

In fact, about the only thing that didn’t change between the two trials was Parkinson’s perspective on the case. The soundbite he delivered after Harper’s 2002 conviction and the comment he offered two weeks ago after her acquittal were almost exactly the same:

“To believe her, a person came into the house in the middle of the night with no forced entry . . . took a steak knife in a darkened kitchen, went down the hallway, turned left, stabbed this little boy to death for absolutely no reason, then struggled with her, didn’t kill her, and left — actually walked away from her in her back yard, pulling off his mask. . . . That’s enough for me,” Parkinson says. “Her story didn’t make sense.”

There’s a certain irony to the fact that Parkinson’s original version of that quote, broadcast May 31, 2002, on the ABC news magazine 20/20, prompted Sells’ confession. Diane Fanning, a true-crime author who was then putting the finishing touches on a book about Sells, happened to be watching that night [see Dusty Rhodes, “Who killed Joel?” July 24, 2003].

Though she thought she had completed her research, Fanning kept up her correspondence with Sells. When she saw Parkinson on TV, she knew that Sells, who had no access to TV, would get a chuckle out of the prosecutor’s blustery quote. So in her next letter Fanning wrote:

The other night, I was watching a story on TV about a woman who was in jail for killing her son. She claims someone broke into her house and killed him. You could say, “Yeah right, lady. We’ve heard that story before.” But then you listen to the law enforcement guys and the prosecuting attorney and they are so full of stupid opinions. When they were asked why they only pursued her in this case, they said: 1) There were no strange fingerprints in the house; 2) No stranger would just come into her house and kill her child; 3) It was so violent, it had to be someone with a very close relationship to the child; (And here’s my very favorite on the stupid scale) 4) A person does not come in to someone’s else [house] without a weapon and then pull a knife out of the kitchen drawer in the house and use it.

She supplied no other details, so she was stunned by Sells’ response: “About that woman claims someone broke into her house,” he wrote, “was that like maybe two days before my Springfield, MO murder? Maybe on the 13th?”

Fanning didn’t remember the date flashed on TV, so she contacted 20/20 and learned that yes, Joel Kirkpatrick had been killed on Oct. 13, 1997. Sells had already been indicted for the Oct. 15 abduction, rape, and murder of 13-year-old Stephanie Mahaney in Springfield, Mo.

This discovery, Fanning says, created a quandary. Her deadline was approaching, and she had no time to substantiate Sells’ claim to this killing. Besides, she had already heard the official legal view by way of Parkinson’s appearance on TV.

“I couldn’t decide whether to put it in my book or not,” she says. “I thought: If I put it in my book and it’s not true, it could damage my credibility — but if it is true, there will be people out there who will read this and know enough to do something about it.”

Fanning’s book, Through the Window, was published in May 2003. A few months later, Springfield private investigator Bill Clutter heard that the book contained a confession that could solve an Illinois murder. He was working with Larry Golden, a professor at the University of Illinois at Springfield, to establish the Downstate Illinois Innocence Project and contacted Harper’s family seeking permission for DIIP students to investigate her case.

Jim and Jane Rea handed Clutter the single three-ring binder that contained all the reports prosecutors had given them before their daughter’s first trial. As Clutter read the documents, he paused on a report from a Greyhound ticket agent at a bus depot in Princeton, Ind., 40 miles southeast of Lawrenceville. This agent, Sandra Wirth, had called police 48 hours after Joel’s murder to report that a “creepy” stranger who looked like the composite sketch she had seen on the news had just been in her bus station. He was nervous and disheveled, Wirth said, and said he wanted to go visit his ailing mother. He requested a ticket to a town Wirth had never heard of — Winnemucca, Nev.

That name — Winnemucca — rang a bell. Clutter leafed through Fanning’s book, and, sure enough, Sells had twice lived in Winnemucca. In fact, he claimed to have committed one of his most colorful crimes there — the murder of a pretty hitchhiker who turned out to be Stefanie Stroh, heir to the Stroh beer fortune.

When Clutter interviewed the Greyhound agent, he discovered that the ticket sold to the “creepy” man would have been good for a whole year and would have allowed a traveler to take one leg of the journey at a time. The first stop would have been at about 4:30 p.m. in St. Louis, where passengers had to disembark for at least 30 minutes to change buses. Sells’ mother lived in St. Louis. And authorities confirm that, three months later, Sells showed up in Winnemucca.

What are the odds that some other “creepy” man who just happened to look like the intruder Harper described bought a bus ticket to a tiny town in Nevada that Sells visited multiple times? To Ed Parkinson, the odds aren’t great, but they’re good enough.

“The person who bought the ticket was 17 to 18 years old,” he snorts, quoting the statement Wirth gave police. (Harper described the intruder as 14 to 17; Sells was then 33.) “By the way,” Parkinson adds, “that night, Tommy Lynn Sells is charged with killing a young girl in Springfield, Mo., which also isn’t one of the [bus] stops.”

The prosecutor finds the idea that Sells could have gotten off the bus, visited his sick mother in St. Louis and driven some 200 miles west to Stephanie Mahaney’s hometown laughable.

“It’s like that movie Planes, Trains and Automobiles,” he says. “I thought John Candy would be popping up pretty soon.”

His contempt for the Sells scenario shows in his response to the memo Harper’s lawyers filed asking the judge to admit Sells’ confession into evidence. The defense pleading was 25 pages thick, augmented with two binders of supporting documents; Parkinson’s answer was a derisive fax that — double-spaced — was barely three pages long. Harper’s team was shocked by the weak response.

“There was not a single citation to authority. It was — you know, there are no words for what it was,” Urdangen sputters.

Parkinson says he and SAAP prosecutor David Rands treated the defense motion with proper respect. “We didn’t think it required 40 pages of legalese,” he says. “Our [pleadings] were sparse — ‘This is the law, Judge. This is all you need.’ We thought that’s all it deserved.”

But as pretrial maneuvering proceeded, the defense lawyers saw such responses as a pattern. Just raising an objection was often enough to persuade the prosecutors to cave in.

“They didn’t file any responsive pleadings any self-respecting law student would ever have considered preparing,” Urdangen says. “That [Sells response] was just one example. Every other thing they filed was the same. That’s why we won all the pretrial motions — mostly because the law was on our side but also because they put up no fight at all.”

Parkinson bristles, but only slightly.

“I think what they’re really getting at is they’re smart and we’re not. They had that air about them, in their filings and their attitude,” he says.

The “Sells crap” wasn’t the only hurdle Parkinson would face in the courtroom. Just as in the first trial, he didn’t have the best facts in his quiver.

No physical evidence linked Julie Rea Harper to the crime; indeed, where anyone would expect the killer to be covered with the victim’s blood, Harper had only a small “transfer” stain of the sort one could get by brushing against someone else who was spattered with blood. Investigators had dug up the septic tank and sprayed Luminol around her house, but these tests yielded no evidence of a cleanup.

Harper’s own assortment of minor injuries — a black eye, two scraped knees, puncture wounds on the tops of her feet, and a nasty cut on her arm that required four stitches — matched her story about struggling with an intruder better than it did the prosecution’s suggestion that they were all self-inflicted.

Nor could Parkinson point to a motive, especially at this second trial, where Harper’s attorneys had won motions to exclude prejudicial testimony that had been previously allowed. Harper’s bitter 1994 divorce from Joel’s father, Len Kirkpatrick, and their subsequent wrangling over custody provided the only hint of impetus. They shared custody, but Kirkpatrick, who had remarried, had residential custody of Joel. Harper had lost an appeal of that ruling about two months before Joel’s murder.

Even Parkinson admits that it wasn’t much for the jury to gnaw on. “You don’t have to prove a motive,” he says, citing the legal standard versus human nature, “but you have to prove a motive.”

Another problem that ballooned in the second trial was the ISP investigation, so flawed that it makes for some near-comic testimony. For example, when Master Sgt. Jerry Pea — one of the two main investigators assigned to Joel’s murder — took the stand to narrate a video he shot of Harper’s house and the crime scene, the picture was dark and muddy. It became clearer as he retraced his steps through the house after someone reminded him to turn the lights on. “It was brighter to me in the viewfinder,” he testified.

Similarly, the pictures the ISP guys took of their fellow investigators holding Joel’s bed linens vertically — photos meant to show knife slits in the covers — were at this trial derided by defense experts who pointed out that what the photos really depicted was hair, fiber, and other potential trace evidence being lost forever.

The crime-scene investigators’ decision not to dust for fingerprints played better at the first trial, when Harper’s story about an intruder sounded more like a bad fairy tale.

Other prosecution witnesses had lost face during the years that elapsed between the two trials. The medical examiner who performed Joel’s autopsy willfully evaded deposition, as did the Lawrence County deputy who discovered Joel’s still-warm corpse. He and another deputy had since left the sheriff’s department under questionable circumstances. When defense attorneys asked about their disciplinary files, the new sheriff testified that the documents had recently been stolen from a locked file cabinet by someone who had the keypad combination to his office.

That left Parkinson with a witness list heavy on Harper’s curiously hostile former neighbors, including one woman who, under cross-examination, refused to admit she had testified before the grand jury or even to look at the transcript of her testimony. “If you say that I said that,” she told Urdangen, “then I believe that you say that I said that.”

The final blow to Parkinson’s strategy came when the defense successfully objected to the performance planned by Rodney Englert, a “crime-scene reconstructionist” and blood-pattern analyst from Portland, Ore., hired by prosecutors to deliver his expert opinion about the physical evidence. Vaughn ruled that Englert could display a poster showing various types of blood spatter (hair swipe, fabric impression, low velocity, castoff) but that he could not stage a demonstration using fake blood inside the courtroom.

Julie Rea Harper’s attorneys didn’t bet the bank on Tommy Lynn Sells. From the first day on, they reminded jurors, Harper, not Sells, was on trial.

“Our defense is that she is innocent,” Urdangen told the jury during opening arguments.

Safer says Sells not only created reasonable doubt but also provided proof that there really are monsters. “It’s hard to even imagine that somebody as dark as that exists,” Safer says. “Whether or not the jury believed that he did this, he provided a vivid example of a psychopath. Just knowing there are people like that out there helped.”

(That said, could Safer — the former chief federal prosecutor — make a case that Sells truly did kill Joel Kirkpatrick? “In a heartbeat. And convict him. Without breaking a sweat,” Safer says.)

At trial, they measured Sells out one dose at a time. The first day of the defense case, they played a cassette tape of his interview with ISP agents; the next day, they had an attorney and a paralegal read a transcript of Sells’ answering a 20/20 producer’s questions. The following day, they played a videotape of a similar unedited interview with a producer from The Montel Williams Show.

In the three interviews, Sells — who has a documented history of mental illness and substance abuse — offered contradictory statements on how he traveled, when and where; on the details of crime scenes; and on his motive for killing. However, he never wavered in his claim that he killed someone on Oct. 13, 1997.

“Do I think I’m the one that killed this kid? Yes. Yes,” Sells told ISP investigators. “Now . . . I don’t give a shit about this [Harper] woman. If I did, I would not have went after her in the first place. I’m callous to that. If it wasn’t this kid I killed, then there’s a murder out there that we still ain’t undug yet.”

The catch, Sells tells the Montel producer, is that his peculiar situation has turned the system upside down

“Problem is, I have to prove my guilt, and that’s not the way the justice system is supposed to work,” he says. “How can somebody prove something that happened half-a-decade ago?”

During the two-week trial, spectators sorted themselves by sentiment — those certain of Harper’s innocence tended to sit on the right side of the aisle, those convinced she’s a killer on the left (her former husband, Len Kirkpatrick — now an ISP trooper — spent every moment of the trial in the front row, on the left). The courtroom was usually full but never crowded until the seventh day — the day Harper was scheduled to testify.

Throughout the trial, she seemed determined to melt into the woodwork. Almost every day she wore some shade of light brown or pale green, something that blended with the paneling, the linoleum, and the fluorescent lighting. If you watched carefully, you would occasionally notice her taking slow, deep breaths, swallowing hard, or reaching for a tissue. When certain witnesses talked about Joel’s wounds, she convulsed with sobs. But she maintained a careful silence until she took the stand.

In her first trial, Harper did not testify. In the intervening years, she’s spoken publicly about the crime just once, in a prison interview broadcast in 2002 on 20/20. But her time on the witness stand was almost anticlimactic. She simply repeated the same story she told investigators in 1997 all over again.

Safer took her through a chronology — growing up in Indiana, marrying young, having Joel at age 18, separation, divorce. On Oct. 11, Joel arrived for his regular weekend visit. They went to nearby Vincennes, had a picnic in a park with a playground. On Sunday, they slept in, had lunch with Joel’s grandparents, went to Wal-Mart, ate at McDonald’s, attended church with some friends. Those friends later joined them at home in Lawrenceville — two moms working on scrapbooks, kids watching a Disney video. Joel was in bed by 10:30 p.m.

When her friends left, around midnight, Harper locked the front door, the back door, and, presumably, the door from the kitchen to the garage. She checked on Joel, then went to bed and slept until being awakened by that scream.

At this point in the story, Harper’s voice was still calm but constricted, as though her words were squeezing out past a lump in her throat.

“I have images that are very clear, and then I have some that are fuzzy, and then I have blank spots in between,” she said.

Unable to tell whether the cry that awakened her came from inside or outside her house, she ran to Joel’s room and found his bed empty. She called his name, and from the opposite side of the bed someone jumped at her, knocked her down, and ran from the house. She caught the intruder at the garage door, which he opened by breaking glass with his elbow. They tussled briefly in the backyard until he smashed her head on the ground. “This person went from just wanting to get away to being mad,” she said.

A wave of small hiccuping sobs overtook Harper as she recalled letting the man walk away. As she composed herself, the judge sent the jury out. When they returned, Harper described going to the neighbors’ house and having them call 911 to report a kidnapping. She didn’t know that her son was lying on the floor, bleeding to death.

Parkinson began his cross-examination by attacking her estimate of the intruder’s age — 14 to 17 (Sells was 33 at the time). “I gave them my impressions at the time,” Harper answered.

Parkinson moved on to whether or not she had locked the back door. Harper wouldn’t give a yes or no answer. “That’s a question I’ve asked myself many times,” she said.

Why did she let the intruder walk away? “I was looking for help for Joel. That man did not have Joel,” she said.

When Parkinson pressed her to explain how a smudge of Joel’s blood ended up on her nightshirt, she couldn’t.

“I can tell you how it didn’t get there,” she finally said. “It wasn’t because I got to see my son. His blood would’ve been all over my T-shirt.”

The final witness called by the defense was ISP officer Brad Phegley, the “case agent in charge” on Joel’s murder investigation. Holding a transcript of Phegley’s testimony given months earlier at Harper’s probable-cause hearing, Safer pounded him with questions that had only two possible answers — “Yes” and “That’s correct.”

The case against Harper is purely circumstantial, correct? There is no physical evidence linking her to the crime, right? There is no motive? No evidence that she ever raised her hand to Joel, no evidence that she ever raised her voice to Joel?

Phegley affirmed every one of those statements.

Safer picked up another document — a six-page memo from ISP Maj. Edie Casella to Col. Charles Brueggemann, analyzing holes in the Harper case. A list of recommendations for further investigation made up the bulk of the memo, and Safer ticked off several items, asking whether Casella’s suggestions had been followed. Each time, Phegley answered no.

A juror contacted after the trial, speaking on the condition that his name not be used, said that the state police “failed miserably.”

The problem could be traced back to the broken glass that lay sparkling on the concrete outside Harper’s back door the night Joel was killed. Anybody could see that the door had to have been wide open when the shards fell. What kind of “intruder” breaks a door that’s already open?

Ken Moses, a retired San Francisco cop who spent 28 years as a crime-scene investigator and has worked 17,000 crime scenes, was hired by the defense to tell the jury how that happened. “It’s a common occurrence in home-invasion crimes where intruder is discovered and makes a hasty exit,” he said. “Once the door violently opens and stops at the apex . . . the glass falls out.”

But the officers who reported to Harper’s Lawrenceville home just saw glass broken out where, they assumed, it should be broken in.

“[The first deputy] saw the glass broken out on the floor in the garage and outside the second door and thought, ‘This is phony,’” Urdangen says, “and that just informed all of their thinking. That’s why their work was so flawed.”

Parkinson disagrees, even though his explanation confirms Urdangen’s theory.

“I don’t think the police did an inadequate job,” the prosecutor says. “I think they went to the crime scene and saw that this didn’t look like an intruder had been in like Julie said and thereafter they tried to get her to explain it.”

The juror, though, said he never heard Parkinson offer any story to counter Harper’s. “I’m open-minded to the end,” the juror says. “To the closing statement, I was waiting for [Parkinson] to say how these events all took place.”

Defense attorney Daniel says she knows why Parkinson offered no story.

“There was no account that they could put together of how Julie could have killed her son, because any account that you could come up with was contradicted by some piece of physical evidence,” Daniel says. “Maybe that’s a good place to stop and reexamine.”

For two years, Julie Rea Harper’s attorneys say, they sent letters asking Attorney General Lisa Madigan’s office to exercise its right to intervene and stop the prosecution of Harper. They were granted a two-hour meeting with Madigan’s three top aides less than a week before jury selection. The official decision let the trial proceed.

“The process was under way, [Harper] had the opportunity for new trial, and her team was in place,” says spokeswoman Cara Smith. “Based on what was presented to us, there was no reason to preempt that process.”

The day after Harper’s trial, Lawrence County State’s Attorney Patrick Hahn made it clear that the jury’s decision meant nothing to him. In a press release, he praised Parkinson as “a man of the highest integrity” and blamed the acquittal on TV shows that have “enhanced” jurors’ expectations.

“There are no plans to charge any other person,” Hahn wrote.

Parkinson, of course, will never consider Harper anything but an evil child-killer.

“You’re going to print ‘Parkinson can never admit he’s wrong,’ ” he says. “Well, I don’t think I’m wrong.”

Contact Dusty Rhodes at [email protected].