Walking down the main business street in Cairo, Ill., it’s tempting to think that this spring’s floodwaters of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers were sent to put the languishing town out of its misery once and for all.

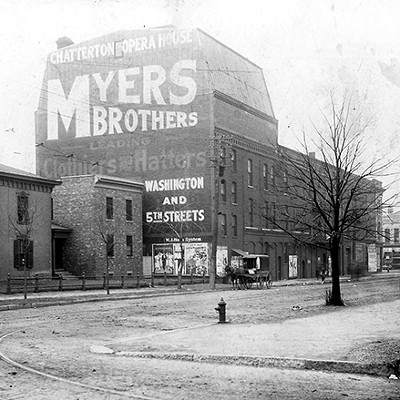

Many buildings along Commercial Street in Illinois’ southernmost town have long been abandoned, left to decay since businesses began departing decades ago. Brick facades crumble to the fractured sidewalks in untouched heaps, and rotting plywood that was meant to keep out trespassers now adds to the rubble, giving the desolate, quiet strip the feeling of a bombed-out war zone or a wild west ghost town. Only a handful of the old buildings are still in use on Commercial Street, among them a tavern and a retail store selling Maytag appliances, both stores flanked by the corpses of former businesses.

In late April and early May, Cairo and numerous other southern Illinois towns along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers faced rising floodwaters that threatened to wipe them off the map, leading Missouri House Speaker Steven Tilley to remark that he’d rather see Cairo underwater than see the Army Corps of Engineers blow up a levee that would flood Missouri farmland. Given that hypothetical choice by a reporter, Tilley remarked with a smile and not even a moment’s hesitation, “Cairo. I’ve been there; trust me. Cairo. Have you been to Cairo? You know what I’m saying, then.”

On the surface, Tilley’s flippancy toward the town’s future seems reasonable. What was once a bustling river city of 20,000 in 1915 is now an atrophied town of only 2,800, and the crumbling downtown, the near total lack of jobs and the prevalent poverty give the impression that the town is dying or already dead.

But a look beneath the surface reveals a different Cairo than the one often portrayed in gloomy stories of promise unfulfilled. Life goes on for the people of Cairo, despite the many projections of their town’s demise, and an enthusiastic new mayor is working to change the future of this historic place.

Older than Illinois itself

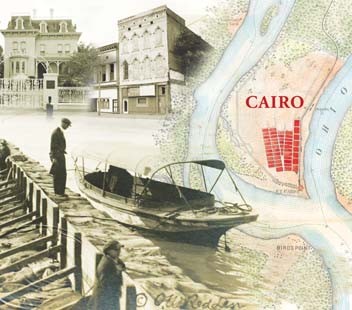

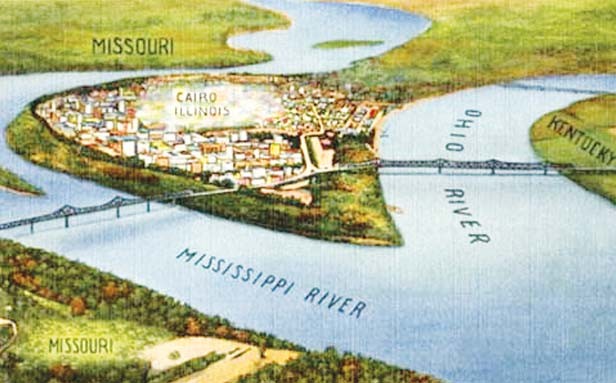

The peninsula on which Cairo (pronounced care-oh) sits had been visited by Europeans as early as 1660, when the Catholic missionary Louis Hennepin explored the area as part of New France. In 1703, French pioneer Charles Juchereau de St. Denys established a fort and tannery there, but it was raided by Native Americans and destroyed. Explorers Lewis and Clark even passed through the area in 1803 before officially starting their expedition to the Pacific Ocean in 1804.

It wasn’t until January 1818 that the city of Cairo was settled in earnest by John Comegys, an explorer and businessman from Baltimore who dreamed of building a great city at the confluence of the two rivers. The name “Cairo” allegedly comes from Comegys’ belief that the area resembled Cairo, Egypt, and southern Illinois has come to be known as “Little Egypt” as a result. Comegys died in 1820, and without his guidance the settlement languished until 1837, when businessman Darius Holbrook of Boston convinced the state legislature to incorporate the Cairo City and Canal Company. The company built a shipyard, houses, a hotel, a store and the first of the town’s many levees.

Historians believe Cairo served as a waypoint on the Underground Railroad before the Civil War, and it became General Ulysses S. Grant’s headquarters for several months during the war. Though Cairo never saw action, thousands of Union troops trained there and fortified the strategic port, which became an important supply depot for Grant’s push into the Confederate south. Thousands of African Americans moved to Cairo during that time, with many more freed slaves moving there at the war’s end. Their presence would shape the city’s future for the next hundred years and beyond.

Cairo grew steadily as river commerce increased, and the federal government recognized its strategic location by building a combination customs house, federal court and post office there in 1872. At one point, the Cairo post office was the third busiest in the United States. Now known as the Cairo Customs House Museum, the building houses Civil War artifacts and numerous other historical items.

Residue of racism

During the civil rights era of the late 1950s and early 1960s, Cairo’s African-American community watched the national struggle for equality with hopeful anticipation, but their own struggle was yet to come. Cairo’s long-simmering powder keg of discrimination and racial hatred exploded on July 15, 1967, when Robert Hunt, a 19-year-old African-American soldier home on leave, was arrested by local police on trumped up charges and later found hanged in his cell. His death was immediately deemed a suicide by the city’s white leadership, but African-American leaders protested to demand justice. What they got was a violent reprisal that precipitated three days of race riots. There had been other incidents of racially-motivated violence in the preceding decades, but Hunt’s apparent murder was a catalyst for change.

For several years following that incident, Cairo was a hotbed of racial tension as African-American citizens pressed for desegregation, equal employment, adequate housing and other civil rights objectives – often with bloody results. Sometimes the city’s white leadership would act spitefully, like when it shut down the public pool and the little league baseball program to avoid integration. African-Americans organized a boycott of white-owned businesses that refused to hire them, but many businesses instead moved across the rivers to Kentucky or Missouri or shut down completely. Some undoubtedly left to spite the protesters, while others simply left to seek a more peaceful business climate without the taint of racial hatred. The boycotts didn’t cause the town’s decline – some people say it actually started when Cairo was bypassed by a railroad bridge at Thebes, Ill., in 1905 – but the racial tension accelerated the loss of population and prestige. From 1960 to 1970, the population dropped from 9,348 to 6,277, and the negative stigma of racism stays with Cairo even still.

Even after the violence and tension subsided in the late 1970s, businesses kept leaving. So many businesses have left the city in the past 40 years that the Custom House Museum keeps a collection of pencils, lighters, key chains and other promotional items given away by now-shuttered businesses. The declining importance of barges for transporting goods also starved the town of jobs and revenue, and Cairo has never recovered.

Persistent poverty

Cairo’s lack of job opportunities exacerbates its poverty rate, which has a ripple effect on other economic indicators. Median income is $30,729 in the northern half of Cairo, which constitutes one of the city’s two census tracts. In the southern half, median income is a mere $11,923, a decrease of 38 percent just since 2000. Fifty percent of Cairo citizens in the northern census tract earn less than $30,000; that’s closer to 68 percent in the southern tract. In 2009, 300 of 629 families within Cairo’s school district were in poverty. Though unemployment figures specifically for Cairo are hard to come by, Alexander County, which contains Cairo, had an unemployment rate of 11.8 percent in 2010. Statewide, that number was 10.3 percent.

The widespread poverty also affects housing and taxes. Half of Cairo’s population rents their housing instead of owning it, compared with the statewide rental rate of 32.5 percent. Meanwhile, about 20 percent of Cairo’s houses are vacant, compared with the statewide rate of only eight percent. Property taxes are high because the tax base is depleted from so many vacant houses and closed businesses, making land ownership expensive.

Constant threat of flooding

Flooding has always been a fact of life for Cairo and the surrounding area, and it’s easy to see why. The city is situated at the confluence of the largest and third largest rivers in the United States, which together drain almost 1 million square miles of land and carried about 699,100 cubic feet of water per second during 2010. That’s more than 5.2 million gallons of water or eight Olympic-size swimming pools rushing past Cairo every second.

And no matter how thick or how high the levee is, the people of Cairo seem to understand one fundamental fact about water: you can stop it from coming through the wall, but you can’t stop it from going under. Water constantly seeps under the levee, requiring the city to maintain a pump system to stay dry.

Cairo has flooded repeatedly since its settlement, despite constant improvements to the levee. Especially high waters swamped the city in 1913, 1927, 1937 and 1961, among other years. An enormous 60-foot-wide gate dating from 1914 and weighing 80 tons sits several yards above Cairo’s main entrance, ready to be lowered into place to seal the levee in case of flooding.

Even though the most recent southern Illinois flood during April and May this year didn’t entirely swamp Cairo, it did cause widespread damage outside the levee, open a series of sand boils that swallowed Cairo streets, cause the partial collapse of a major train overpass atop Cairo’s levee and force an evacuation of the city because the pump system couldn’t keep up with the heavy rains and seepage.

As the water approached the top of the levee, the Army Corps of Engineers decided to blow up a separate levee constructed to relieve flooding along the Mississippi River. That action would instead flood the Birds Point-New Madrid Floodway in Missouri, for which the federal government purchased an easement decades before, specifically to accept floodwaters threatening towns along the rivers, but the Missouri farmers who own the land filed a lawsuit to stop the levee from being blown up. Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan fought the lawsuit, winning a decisive victory that allowed the levee to be blown. It was during that legal fight that Missouri Speaker Tilley’s comment angered Cairo citizens.

“The Missouri people kept saying it was to save Cairo, but Cairo’s just a reference point because this is where the [flood] gauge is,” says Cairo fire chief John Meyer. “It saved several communities, and once they blew the levee, at Olive Branch, all the water was gone within a day or two. It was that significant, and everybody was wanting to say it was just ‘poor ol’ Cairo’.”

[CORRECTION: A previous version of this story said the federal

government purchased the Missouri land that was eventually flooded by

the blown levee. That is incorrect. The federal government actually

purchased an easement from the landowners, absolving the government of

damages in the event that the levee was blown. Though the government was

not able to obtain easements for all of the land, the court held that

the owners of the land without easements were already entitled to

damages through a separate law, noting that the disputed land was

already subject to natural flooding. The court essentially said the

landowners had no reason to file a lawsuit to stop the levee being

blown. We apologize for the incorrect information.]

Hope and a plan

Cairo mayor Demetrius Coleman has only been in office for a couple of months. He was sworn in during the recent flood crisis and spent his first night in office helping reinforce the levee with sandbags. It’s no surprise that Coleman has hit the ground running. He didn’t have a choice; it was almost literally sink or swim.

Coleman grew up in Cairo, moving away to join the Marines but later returning to live after he visited his hometown on vacation 26 years ago and realized it needed help. He worked as a self-described “community activist,” resuscitating the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), while also taking on the role of church pastor. He was later elected to a seat on the city council.

“I just felt that this community deserved better,” he says. “It took the political process for me to get to this position, but I’m not a political person, and I’ve felt that this has been one of the big contributing factors to this community being where it’s at – the politics. My focus is bringing people together.”

While walking around the large sinkholes that swallowed part of Cairo’s Commercial Street, Coleman explains that the flood was actually a blessing in disguise. The high waters revealed that the city’s pump system needs a major overhaul after years of neglect by previous administrations, and it focused state and federal attention on the city’s plight. U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin visited Cairo during the flooding, and Gov. Pat Quinn arrived later to view the damage. As a result, Cairo could get as much as $4 million in federal funds to update its pump system. President Barack Obama recently declared several southern Illinois counties, including Alexander County, to be disaster areas, making citizens of those counties eligible for grants and low-cost loans to pay for home repair and cleanup costs, among other resources.

But Coleman isn’t content to focus solely on responding to the flood. He has much bigger plans for Cairo. One of his main goals is to clean up the city’s overall appearance to make it more attractive for businesses. In early June, he signed paperwork authorizing the demolition of several abandoned buildings downtown, which he estimates will begin after the July 4 holiday weekend.

“When I was growing up, people wanted to come to Cairo,” he says. “This was one of the most viable points in the area. People came here to shop, they came here for medical treatment, and they came here for entertainment, so we have to do things that spur some of that on again – just simple things like cleaning the city up.”

It’s his belief that businesses won’t begin to return until Cairo is more attractive, so he’s hoping to enlist the help of local churches and community groups to clean up the city. His administration is also enforcing long-ignored city ordinances on abandoned cars and buildings while putting together a master plan for redevelopment – the first since the 1950s.

And after years of bad management in which the city’s government failed to create a budget, maintain infrastructure, keep records or hold meaningful public meetings, Coleman’s administration and that of the previous mayor have righted the ship, attempting to control the city’s finances and debt. That won’t be easy, Coleman concedes, noting that it’s costing about $22,000 each month to run the city’s pumps, and it will likely take until August to completely rid the city of unwanted water.

Coleman says he is working to not only clean up Cairo, but to renew the minds of its people.

“Until you affect those two areas, nothing can change,” he says. “It was just like a spirit of hopelessness had fallen over this immediate area…. We have to live like people and consider one another as neighbors.”

Despite the negative stigma surrounding Cairo’s racially-charged past, Coleman says the race issue has faded significantly since the days of riots and lynch mobs. The city is now 71 percent black, according to the latest census numbers, and African Americans now hold several positions of power.

“I’m the black mayor,” he says with a laugh. “The city council is predominantly black, so you can’t say it’s a major factor anymore. We’re an economically-deprived community, so that’s become a greater factor than race. We’ve moved beyond that. It’s still present, but it just doesn’t affect the community the way it did then.”

In some ways, Cairo is like many other small towns in Illinois left behind as Americans migrated to urban centers and to the West. Agriculture jobs have dried up, highways have bypassed small communities, and businesses have moved to be near the urban action. Cairo has long been touted as a great city waiting to happen, but perhaps its future holds something else. It more than likely will never again be the bustling city of yesteryear, but it has an opportunity to purposefully recast itself as a small town with potential.

“You can’t continue to say you want something different, while you continue doing the same thing,” Coleman says. “We’re all in the same boat, and we’re continuing to sink, so we have to find a way of saving ourselves from sinking any further.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].