“They’re just not elegant anymore,” my mother sighed.

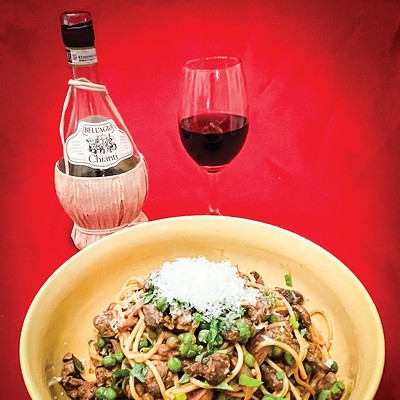

Horseshoes? Elegant? Springfield’s iconic dish that almost inevitably appears on our pubs’ and casual eating establishments’ menus? The gargantuan pig-out preparation beloved of Springfield area residents that’s often viewed with disbelief by visitors? “Do you folks actually eat those things?” asked Peter Segal, host of NPR’s “Wait, Wait, Don’t Tell Me” when the show was broadcast from the PAC a few years ago. In their book, 500 Things to Eat Before It’s Too Late, “Roadfood’s” Jane and Michael Stern describe horseshoes as “unbridled plebeian opulence.”

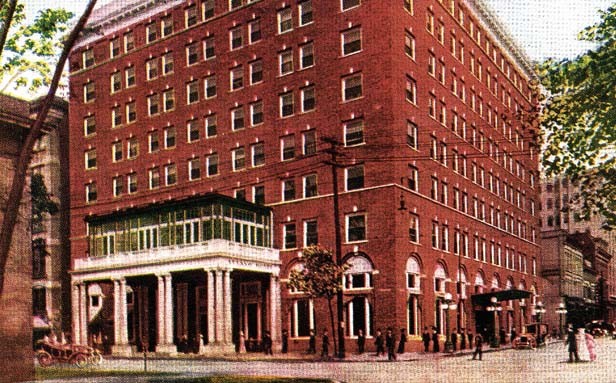

But for a long time, horseshoes really were elegant. They were created and served in Springfield’s most elegant restaurant in what was Springfield’s most elegant hotel. I know, because I ate my first horseshoes there in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

It was one of my most special childhood treats, and by far the one that made me feel most grown-up. Every so often my grandfather, Robert Stevens, who was a realtor, would take me to lunch in the Red Lion Room at the Leland Hotel. My entire family dined in the Red Lion Room occasionally for birthdays or other celebrations. But when my grandfather took me to lunch there, it was just the two of us. We’d order horseshoes, and then eat quietly so we could listen in on the political wheeling and dealing going on all around us.

It was an awe-inspiring experience for a young child. I’d squirm a bit, because my starchy petticoats and the stiff ruffles on the back of my underpants were itchy. But the horseshoes were wonderfully delicious; and the “Olde English” decor as well as the waitresses’ faux-medieval outfits – long velvet (velveteen?) dresses in deep jewel-tones of red, green and gold with laced bodices and matching jeweled caps – made the Red Lion Room seem like something in a magic castle from a fairy tale. And listening to the political goings-on made me feel important, even if I didn’t understand much of it.

Those horseshoes were made with two slices of homemade-type white bread not more than a half inch thick. The ham was thinly sliced from a bone-in ham, which provided the horseshoe shape from whence the sandwich’s name came; other meat choices were also thinly sliced, and the chicken or turkey was roasted in house – never (Heaven forbid!) from highly processed chicken or turkey “roll.” The cheese sauce covering the meat and toast was tangy, and the handful of crisp fries that topped it were made from fresh potatoes. The sandwich was served on a preheated steak platter just slightly larger than the two pieces of toast.

Over time, though, horseshoes morphed into something that, although recognizable as descendants of the original, has become a far cry from those I first ate. I don’t know exactly when it happened, but I suspect it must have begun in the 1970s when I was away at college and then Chicago. And I don’t know why, although my guess is that local restaurant owners and chefs began competing for horseshoe customers by offering ever-larger portions. But horseshoes were always rich and filling – even the half-portions known as ponyshoes. Has there ever been anything less appropriate to super-size? The toast is now Texas (usually Wonderbread-type), meats are piled on, and options now include hamburger patties as well as breaded and fried whole chicken breasts and pork tenderloins. The platters are larger, filled to the brim with cheese sauce that’s rarely as tasty as the original (even when it claims to be) and the handful of fries or wedges from freshly cut potatoes has become a mountain of usually crinkle-cut frozen fries drenched in more cheese sauce.

Super-sized horseshoes have become so ubiquitous that most people – even locals – now think they’re the original version. They’ve been featured as such on TV in shows such as “Burt Wolfe’s Travels and Traditions” and “Man Vs. Food,” hosted by Alan Richman, and in travel books and guides like the Sterns’. Websites such as Wikipedia and What’sCookinginAmerica.net inaccurately describe classic horseshoes.

I have my childhood memories of horseshoes, as well as a recipe for “Original Leland Horseshoe Sauce” (p.16) written in my grandmother’s beautiful copperplate cursive. I was pretty sure it was the original – or at least close to it – because of my taste memory. But I’ve long wanted to nail down horseshoes (pun intended), to establish beyond doubt their origins and exact composition.

Thanks to local history buff Tony Leone, at last I’ve been able to do so. Leone is more that just a history buff. He’s been appointed by the Illinois House to the Illinois Capitol Historic Preservation Board and by the governor as a trustee of the Illinois Historic Preservation Board. Owner/innkeeper of the Pasfield House, which he beautifully renovated in 2002, Leone was named the 2011 Preservationist of the Year, winning the Springfield Mayor’s Award for Historic Preservation. When Leone handed me an inches-thick file, I found horseshoe pay dirt.

Leone’s interest in horseshoe history resulted from his acquisition of the Pasfield House, and its owners’ connection to the Leland Hotel. The first Leland was opened in 1867. According to a July 1909 Springfield Chamber of Commerce newsletter, it was considered “one of the best hotels in the West” and the prime reason a serious attempt by Peoria and another by Decatur to “steal” the capital failed, because a sufficiency of quality hotel accommodations was crucial for out-of-town legislators. “In the history of the Capital the name of the Leland Hotel…has ever been a point of vantage which has turned the tide of many a battle and brought home the spoils to Springfield,” it says.

A 1908 fire destroyed the original Leland Hotel. Though it had been privately owned, Springfield’s citizens were concerned enough about the consequences of its loss that the Chamber of Commerce formed a committee to build a new hotel and fund it with public subscriptions. The $125,000 raised was “the largest amount of money ever raised in Springfield by public subscriptions for any purpose,” the newsletter says. “We, all of us, know that with the Leland standing, Peoria would never have thought of attempting to “lift” the Illinois State Fair and that with the promise of the new building, their claims melted into nothingness.” George Pasfield, Jr., whose family was one of Springfield’s oldest and wealthiest, was president of the new Leland Hotel’s board of directors, and other Pasfields were in charge of its construction.

The Leland’s grandeur gradually faded, and it eventually closed. Its only enduring legacy is the horseshoe (five horseshoes were the Red Lion Room’s last meals, served even as the electricity was being cut off in October, 1970).

Over the years several chefs have claimed credit for inventing the horseshoe, most notably Steve Tomko, who worked at in the Leland’s kitchen in the 1920s and eventually became chef at Wayne’s Red Coach. But multiple corroborating documents in Leone’s file all point to one man: Joe Schweska. Some of those and others also confirm that my grandmother’s recipe is indeed the original, and attest to horseshoes’ original components and construction. There were surprises in the file, too, the biggest being that since Schweska created the first horseshoes in 1928, the original sauce was made with “near beer.” (Prohibition ended in 1929.)

In the State Journal’s 1938 Christmas edition, Robert Woods writes “At the Leland Hotel, Chief Chef Joe Schweska has his own recipe for Welsh rarebit sauce which he has been graciously giving to hundreds who have asked for it in the years since he has been serving it.

“Chef Schweska has a score of years in the kitchen behind him and estimates that he serves six gallons of his rarebit sauce a day at the Leland.”

The article continues with Schweska describing how he uses the sauce for horseshoes (though not naming them as such), and then giving the recipe.

Welsh rarebit is a classic U.K. dish of toast covered with cheese sauce. Some say the term “rarebit” is derived from “rabbit” and legend has it that the dish was created by poachers who came home empty-handed. Another regional specialty based on Welsh rarebit is the Kentucky Hot Brown, created at Louisville’s Brown Hotel in 1926. It consists of toast topped with sliced turkey, bacon and tomato slices smothered in Mornay sauce, traditionally made with Swiss-type cheese. There seems to be no evidence that Hot Browns and Horseshoes have a connection of their own.

In an undated column, Bob Gonko, food jounalist and editor for the S J-R for 41 years (1955 to 1996) writes:

“….new information has turned up regarding Springfield’s Horseshoe, our unique sandwich with the cheese sauce topping.

“Tony Wables Sr. worked in the late 1920s as a teen-ager at the old Leland Hotel with Augie Schilling and Steve Tomko:

“‘I was 18 and Steve was 17, I think – we were just kids – and Joe Schweska, the chef at the Leland, taught us and Augie how to cook. I started out as a pan man, a pot washer.

“‘When Joe Schweska started the horseshoe at the Leland in 1928 or 1929, he used ‘near beer’ in the cheese sauce or Welsh Rarebit because it was during Prohibition and you couldn’t legally get alcohol.

“‘In the original horseshoe, the French fries were wedges. You’d take a potato, cut it three times, then use eight of these wedges to represent the nails of the horseshoe.

“‘Now,’ said Wables, ‘you use long branch, julienne, shoe string cuts for French fries. The horseshoe [made with] ham came first,’ he said. ‘Then Joe started adding chicken [to the meat options], then the bacon and tomato.

“‘If you use a good Cheddar cheese, then you have a good sauce. And we always used beer in the sauce.

“‘The thing I liked about Joe Schweska is that he taught me everything I know about cooking,’ said Wables.”

The horseshoe sandwich begins with two pieces of toast on a preheated platter, covering the toast with an entrée. Top with the cheese sauce and surround with French fries, explains Gonko in the article.

What’sCookinginAmerica.net may have gotten the ingredients for classic horseshoes wrong (thick toast, thick-sliced meat, white cheddar sauce) but its 2008 first-person account of Springfield resident Tom McGee confirms other documents and says that though Schweska created horseshoes, the initial idea was his wife’s:

“What knowledge I have of the Horseshoe Sandwich, I have from my deceased brother-in-law, Joseph E. Schweska, Jr., and to a lesser degree from personally knowing Chef Joe Schweska. My brother-in-law often helped his father after school or when special events or parties were being held at the Leland Hotel.”

“The actual idea for the Horseshoe Sandwich came from Elizabeth Schweska, Chef Joe Schweska’s wife. Chef Schweska came home one day and remarked to his wife that he needed a new lunch item for the Leland Hotel’s restaurant menu. She had seen a recipe using a Welsh Rarebit Sauce and suggested the possibility of an open-faced sandwich using this sauce. Joe Schweska liked the idea and developed his own sauce and… sandwich creation, ‘The Horseshoe.’”

“The first Horseshoe was originally made from ham cut from the bone in the shape of a horseshoe. The first potato (the nails) were wedges of potato (not the frozen French fries used today)…. the sauce was poured over the meat and bread and the potato was on top instead of sauce being poured over the whole works. Originally, it was a potato cut in eight wedges.”

That’s it – that’s the original horseshoe, just as I remember it, although at some undetermined point before my time, the potato wedges had been replaced by fries. But only a handful of them, and always made from freshly hand-cut potatoes.

I have no problems with variations on classic dishes, including horseshoes. Breakfast horseshoes, riffs on horseshoes such as the late Caitie Barker’s wildly over-the-top version of cornbread, pulled pork, hot chili powder-spiked cheese sauce, and sweet potato fries – even the mountainous version typically served today, if that’s what you like – are fine with me. Just don’t claim they’re the original.

Contact Julianne Glatz at [email protected].

RealCuisine Recipe

The original Leland Hotel horseshoe sauce

Wables was right: the secret to good horseshoe sauce is good cheddar. Use at least sharp cheddar; I prefer extra-sharp. The original specifies Kraft’s Old English Cheddar. Apparently it’s still produced, but I’ve never been able to find it. Do NOT use pre-grated cheese; it’s coated with a substance that keeps the shreds separate, which isn’t harmful, but keeps pre-grated cheese from completely melting into sauces.

Using good beer is also essential for great horseshoe sauce. I have no idea what kind of beer was used in Schweska’s original, although I’m sure the sauce was tastier once he could use real beer. I use an English ale such as Bass, or English-style IPA for maximum flavor and because of the sauce’s Welsh rarebit connection.

This sauce is so delicious it’s tempting to eating spoonfuls right from the pan. I also use it as a base for cheese soup, macaroni and cheese and more.

- 1/2 c. unsalted butter

- 1/2 c. all-purpose flour

- 1 tsp. salt

- 1/4 tsp. dry mustard

- 1/8 tsp. cayenne

- 2 c. whole milk, at room temperature

- 1 T. Worcestershire sauce

- 8 oz. sharp cheddar, grated

- 3/4 c. beer, at room temperature

Melt the butter in a large heavy saucepan over medium heat. Add the flour and stir with a wooden spoon or whisk to combine. Cook for a couple minutes so the flour loses its raw taste.

Whisk in the milk, salt, mustard and pepper. Bring to a simmer and cook, stirring constantly, until the mixture is quite thick.

Remove the saucepan from the stove. Add the Worcestershire sauce and the cheese, and stir until the cheese is completely melted .

Whisk in the beer, and return the saucepan to the stove. Cook, stirring constantly, until the sauce comes just to a bare simmer. Do not let it boil.

Makes approximately 1 quart.