“People would stop him on the street”

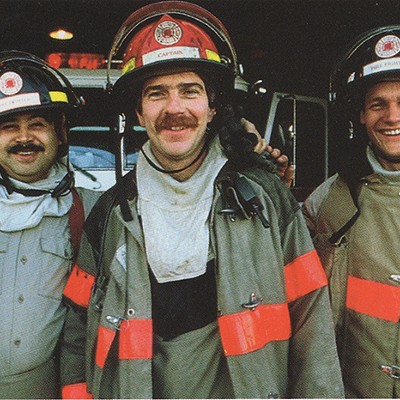

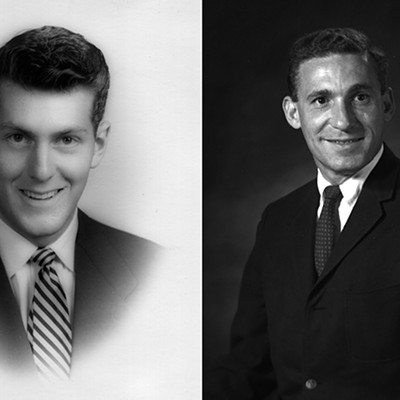

MICHAEL PATRICK MANNING July 26, 1947-Nov. 17, 2020

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

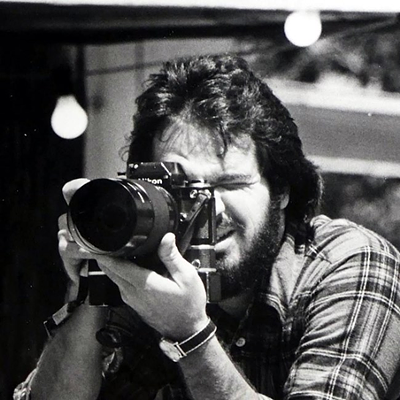

Once one of Springfield’s most popular artists, Michael Manning created an untold number of paintings.

His work is displayed in banks, law offices, living rooms and restaurants throughout the city. He also created less-popular portraits of former Gov. Jim Edgar and former U.S. Sen. John Kerry.

“People would stop him on the street constantly and ask him to do a piece,” recalls John Paul, owner of Prairie Archives, who once rented studio space to Manning. “Five hundred dollars was the usual price, I think. I doubt he got much more than that.” Artistically, Manning peaked during the 1990s and early 2000s. He was Stan Lee, Grant Wood and Colin Campbell Cooper rolled into one, and on acid – he called it “cartoonorealism.”

“I started drawing pictures the way I saw the world and not copying anyone else’s stuff,” Manning told Illinois Times in 2003. He would talk to anyone, anywhere – kids in grocery stores, strangers in restaurants, passersby when he set up his easel outside.

“How do you like being on the jury?” Manning asked a juror during a lunch break when he spotted her near the Old State Capitol during a federal corruption trial that touched on Edgar, according to a 1997 State Journal-Register story. At the time, Manning was painting a picture of Edgar dressed in a tutu while piloting a unicycle on a tightrope above alligators – he told the juror, who reported the encounter to the judge, to avert her eyes, according to the newspaper report. Nothing but small talk, Manning said, and the trial proceeded.

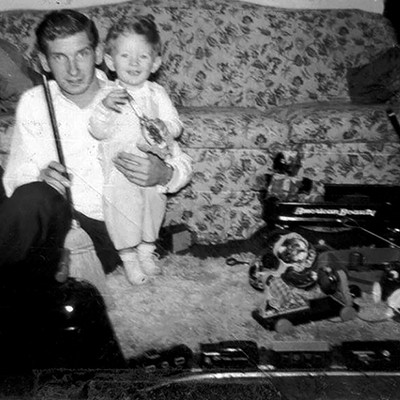

Raised in Dupo, near East St. Louis, Manning’s father was an abusive alcoholic who had spent time as a prisoner of war after the Japanese captured Wake Island, says Caitlin Darling, Manning’s daughter. Manning was 17 and so needed parental permission when he decided to enlist in the Marines. “They were kind of like, ‘Good luck’ – his dad was pissed about it, as I understand,” Darling says.

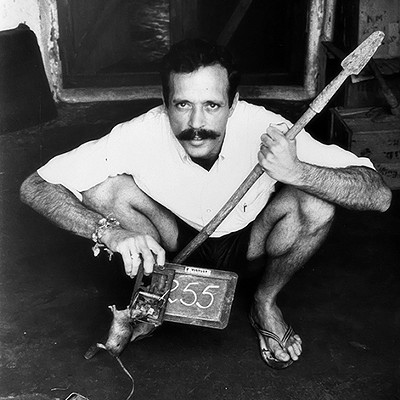

After one tour in Vietnam, Manning went back and never was the same. Duties included loading bombs and dropping flares from planes in combat zones. Paul, who became Manning’s friend after becoming his landlord, says that he once talked about crawling into an empty 55-gallon drum at the edge of an airfield to escape artillery. “He was in the middle of plenty of combat,” Paul says. “Lots of bullets going over his head.”

Manning returned from war with psychological issues that included post-traumatic stress disorder and bipolar disorder. He drank and drugged to excess. He was hospitalized. He pushed on. “He was very functional – even when he was dysfunctional, he was functional,” Darling says.

Manning was elected student body president while at Southern Illinois University-Edwardsville, and he ran for state senate in 1981. With a degree in journalism, Manning came to Springfield in 1985 and became a spokesman for the Illinois State Museum, Department of Professional Regulation and other state agencies. He went through two divorces. Manning was laid off shortly after Edgar took office in 1991, and the governor became a target. A painting of Edgar in dominatrix garb prompted a 1994 visit to Manning’s studio by the governor’s security detail.

He had a fondness for pastels. “The beauty of the pastels is the best reliever of stress,” Manning told the SJ-R in 2002.

Manning’s artistic career began, his daughter recalls, after he and a girlfriend established a resume-writing service in downtown Springfield. Manning had taken a few art lessons at Benedictine University, Darling says, and had gotten tips from the late George Colin, a Salisbury folk artist. The resume-writing business proved slow, and Manning started drawing at work. “At some point, someone came in and wanted to buy one,” Darling says. Manning had varied tastes and wide interests. He knew the words to Jim Croce songs. “He loved to read – he truly is one of the smartest people I’ve ever known,” his daughter says. “He read book upon book upon book. He could tell you about science and art and music – any movie. … He would listen to Vivaldi and then turn on hard rock. When he was older, he would listen to rap.”

Manning asked to rent studio space not long after Paul bought the Prairie Archives building in 1992. “I didn’t know anything about him whatsoever,” Paul says. Manning wasn’t much at business and didn’t prosper despite a market for his work. Paul says that he stopped being a landlord about a decade ago, after discovering that Manning was paying for studio space elsewhere: Why pay for two places, he asked the tenant who had become his friend. There were occasional short-term loans. “For most of his creative career, he was barely ahead of the curve, in a sense, barely able to survive,” Paul says.

As a painter, Manning would take some direction, but only some. “You can’t control him, you can’t tell him what to do,” says Tony Leone, owner of Pasfield House, who commissioned a painting of the bed-and-breakfast in 2003. Abiding by instructions, Manning depicted woodwork beneath the home’s porch. “It’s really cool,” Leone says. “I think I paid $1,000. I didn’t argue.” Manning refused a plea to erase a wheelbarrow depicted in the yard, Leone recalls, and became upset when his painting was displayed on the second floor of Pasfield House instead of the first.

Until last year, Manning lived on State Street and had a studio on English Avenue. He spent days at Caribou Coffee on MacArthur Boulevard, reading and chatting with people. “He always said, ‘I’m a good friend with this guy and a good friend with that person,’” Paul recalls. “Mike considered anyone he got to see or talk to for 15 minutes, he was their very best friend.” Recent years saw Manning’s studio fall into disrepair. He had car accidents. He wasn’t painting, but thought he was: See, he told his daughter last year as she showed off a half-finished artwork he said he was working on. He’d already painted in a completion date: 2016.

Doctors diagnosed dementia in the fall of 2019. Manning lasted 10 days at a Springfield retirement center. After falling four times in 10 days, he went to a Veterans Administration facility in Danville nearly a year ago. They kept COVID out of his ward until October. When Manning fell ill, rules were bent so Darling could see her dad. “When I went in there, his oxygen level rebounded and he said, ‘How are you?’” Darling recalls. “It was so Mike Manning.”

He died shortly afterward from complications of COVID-19. Nurses, Darling said, cried when she retrieved her father’s belongings. “There was someone holding him at the end so he wasn’t by himself.”

His work is displayed in banks, law offices, living rooms and restaurants throughout the city. He also created less-popular portraits of former Gov. Jim Edgar and former U.S. Sen. John Kerry.

“People would stop him on the street constantly and ask him to do a piece,” recalls John Paul, owner of Prairie Archives, who once rented studio space to Manning. “Five hundred dollars was the usual price, I think. I doubt he got much more than that.” Artistically, Manning peaked during the 1990s and early 2000s. He was Stan Lee, Grant Wood and Colin Campbell Cooper rolled into one, and on acid – he called it “cartoonorealism.”

“I started drawing pictures the way I saw the world and not copying anyone else’s stuff,” Manning told Illinois Times in 2003. He would talk to anyone, anywhere – kids in grocery stores, strangers in restaurants, passersby when he set up his easel outside.

“How do you like being on the jury?” Manning asked a juror during a lunch break when he spotted her near the Old State Capitol during a federal corruption trial that touched on Edgar, according to a 1997 State Journal-Register story. At the time, Manning was painting a picture of Edgar dressed in a tutu while piloting a unicycle on a tightrope above alligators – he told the juror, who reported the encounter to the judge, to avert her eyes, according to the newspaper report. Nothing but small talk, Manning said, and the trial proceeded.

Raised in Dupo, near East St. Louis, Manning’s father was an abusive alcoholic who had spent time as a prisoner of war after the Japanese captured Wake Island, says Caitlin Darling, Manning’s daughter. Manning was 17 and so needed parental permission when he decided to enlist in the Marines. “They were kind of like, ‘Good luck’ – his dad was pissed about it, as I understand,” Darling says.

After one tour in Vietnam, Manning went back and never was the same. Duties included loading bombs and dropping flares from planes in combat zones. Paul, who became Manning’s friend after becoming his landlord, says that he once talked about crawling into an empty 55-gallon drum at the edge of an airfield to escape artillery. “He was in the middle of plenty of combat,” Paul says. “Lots of bullets going over his head.”

Manning returned from war with psychological issues that included post-traumatic stress disorder and bipolar disorder. He drank and drugged to excess. He was hospitalized. He pushed on. “He was very functional – even when he was dysfunctional, he was functional,” Darling says.

Manning was elected student body president while at Southern Illinois University-Edwardsville, and he ran for state senate in 1981. With a degree in journalism, Manning came to Springfield in 1985 and became a spokesman for the Illinois State Museum, Department of Professional Regulation and other state agencies. He went through two divorces. Manning was laid off shortly after Edgar took office in 1991, and the governor became a target. A painting of Edgar in dominatrix garb prompted a 1994 visit to Manning’s studio by the governor’s security detail.

He had a fondness for pastels. “The beauty of the pastels is the best reliever of stress,” Manning told the SJ-R in 2002.

Manning’s artistic career began, his daughter recalls, after he and a girlfriend established a resume-writing service in downtown Springfield. Manning had taken a few art lessons at Benedictine University, Darling says, and had gotten tips from the late George Colin, a Salisbury folk artist. The resume-writing business proved slow, and Manning started drawing at work. “At some point, someone came in and wanted to buy one,” Darling says. Manning had varied tastes and wide interests. He knew the words to Jim Croce songs. “He loved to read – he truly is one of the smartest people I’ve ever known,” his daughter says. “He read book upon book upon book. He could tell you about science and art and music – any movie. … He would listen to Vivaldi and then turn on hard rock. When he was older, he would listen to rap.”

Manning asked to rent studio space not long after Paul bought the Prairie Archives building in 1992. “I didn’t know anything about him whatsoever,” Paul says. Manning wasn’t much at business and didn’t prosper despite a market for his work. Paul says that he stopped being a landlord about a decade ago, after discovering that Manning was paying for studio space elsewhere: Why pay for two places, he asked the tenant who had become his friend. There were occasional short-term loans. “For most of his creative career, he was barely ahead of the curve, in a sense, barely able to survive,” Paul says.

As a painter, Manning would take some direction, but only some. “You can’t control him, you can’t tell him what to do,” says Tony Leone, owner of Pasfield House, who commissioned a painting of the bed-and-breakfast in 2003. Abiding by instructions, Manning depicted woodwork beneath the home’s porch. “It’s really cool,” Leone says. “I think I paid $1,000. I didn’t argue.” Manning refused a plea to erase a wheelbarrow depicted in the yard, Leone recalls, and became upset when his painting was displayed on the second floor of Pasfield House instead of the first.

Until last year, Manning lived on State Street and had a studio on English Avenue. He spent days at Caribou Coffee on MacArthur Boulevard, reading and chatting with people. “He always said, ‘I’m a good friend with this guy and a good friend with that person,’” Paul recalls. “Mike considered anyone he got to see or talk to for 15 minutes, he was their very best friend.” Recent years saw Manning’s studio fall into disrepair. He had car accidents. He wasn’t painting, but thought he was: See, he told his daughter last year as she showed off a half-finished artwork he said he was working on. He’d already painted in a completion date: 2016.

Doctors diagnosed dementia in the fall of 2019. Manning lasted 10 days at a Springfield retirement center. After falling four times in 10 days, he went to a Veterans Administration facility in Danville nearly a year ago. They kept COVID out of his ward until October. When Manning fell ill, rules were bent so Darling could see her dad. “When I went in there, his oxygen level rebounded and he said, ‘How are you?’” Darling recalls. “It was so Mike Manning.”

He died shortly afterward from complications of COVID-19. Nurses, Darling said, cried when she retrieved her father’s belongings. “There was someone holding him at the end so he wasn’t by himself.”

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!