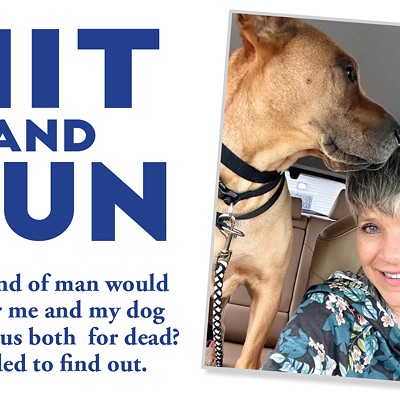

Karyn’s killers?

For the first time, the Slovers tell their story

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

So much about the Slover family seemed just plain

normal. Mike, the dad, earned his living doing construction work and

running a used-car lot called Miracle Motors. Jeanette, the mom, was a

homemaker and full-time babysitter to their grandson, Kolten, and another

little boy.

Mike and Jeanette had two grown children — a

daughter, Mary, who lived in Springfield and worked for the state, and a

son, Michael Jr., who held a couple of security jobs in Decatur and dreamed

of becoming a police officer.

“Homebodies” is the word Mary and Michael

Jr. use to describe their parents. A night out meant dinner at a fast-food

restaurant and maybe a movie. Usually, they were happy to simply hang

around their Mount Zion home, grill some pork chops, and watch PBS or the

History Channel. “Not a real exciting life there,” Mary says.

But when Michael Jr.’s ex-wife, Karyn, vanished

one Friday night, only to turn up days later not just dead but dismembered,

the cops eventually concluded that Mike and Jeanette were horrendously

abnormal. Police say the Slovers had lured the beautiful 23-year-old blonde

to Miracle Motors, where they shot her seven times in the head, butchered

her corpse with a power saw, and dumped her remains into Lake Shelbyville.

The cops also figured that Michael Jr. pitched in to help his parents

conceal this ghastly crime.

The case against the Slovers was purely

circumstantial. No murder weapon was ever found. No bloody power tool. No

physical evidence — except a dog hair from the family pet and a few

buttons and rivets that matched Karyn’s clothes. With so little to go

on, prosecutors couldn’t even offer a clear narrative of who pulled

the trigger and who wielded the saw.

Yet a hometown jury convicted all three Slovers of

first-degree murder, and the judge sentenced them to 60 years in prison.

The two Slover men were given additional five-year sentences for

concealment of the homicide.

All along, the family claimed innocence. Mary, the

only Slover still free, says her folks couldn’t have killed Karyn

because, for one thing, they’re just normal. “I know what was

done to Karyn. They couldn’t wait to shove those pictures in front of

me at the grand jury,” Mary says. “I saw what was done to

Karyn, and normal people don’t do that.”

During the years between Karyn’s murder in September 1996 and the Slovers’ arrest in January 2000, the family didn’t talk to the media. At their trial, a court reporter read their grand-jury testimony into the record; the Slovers’ attorneys advised them not to take the stand. They’ve never before told their side of the story. Denise Ambrose, the attorney handling the Slovers’ case at the Office of the State Appellate Prosecutor, declined to comment. Richard Current, Macon County first assistant state’s attorney refused to answer any questions for this article and said he was also speaking on behalf of state’s attorney Jack Ahola as well as the lead investigator in the case, Mike Mannix, and Karyn’s parents, Larry and Donna Hearn.

To interview the Slover family, one must spend days driving several hundred miles in different directions. Jeanette is in the Dwight Correctional Center, 125 miles northeast of Springfield; Michael Jr., is in the Menard Correctional Center, 150 miles southwest of here. Michael Sr., called Mike by the family, was in Statesville, at Joliet, but was transferred to Pontiac, about 100 miles northeast of Springfield, in December.

Mary visits them as often as she can — her brother twice a month, her parents every six weeks. The separation from one another is the worst part of their punishment. Whatever else anybody thinks of them, they are a tight family. Mike and Jeanette grew up next door to each other in St. Louis, married young, and maintained a relationship so close that their kids took pride in it. “Mom and Dad enjoyed each other’s company,” Michael Jr. says. “It’s more than just husband and wife; they are friends.”

That closeness was a factor in their downfall. Content with each other, they didn’t have many friends. They didn’t belong to any social clubs, weren’t regulars at any church or any tavern. On the night Karyn disappeared — Sept. 27, 1996 — they say they were home watching a British comedy. They were each other’s alibi. In fact, prosecutors say the Slovers’ familial bond was so intense that it became sinister. According to their theory, Karyn — an aspiring model — received a temporary job offer from a Georgia-based modeling agency. The Slovers killed her that very day because they were afraid that she would take Kolten, then 3 years old, and move out of state. Considering that premise, it’s surprising to discover how much affection the Slovers seem to have had for Karyn. Asked open-ended questions — what was Karyn like? — they offer fond anecdotes. “One time, we’re lying in bed and she just all the sudden turns to me and said, ‘What would happen if I ran out of dishwasher detergent and I just put some liquid stuff in there?’ And I said, ‘Man, there would probably be soap bubbles everywhere!’ ” Michael recalls. “She jumps up and runs into the kitchen, and I hear ‘Michael? Can you come in here?’ There were soap bubbles all across the floor. She kept you laughing,” he says. “She was funny. She was constantly doing stuff like that.”

Their divorce was as much Michael’s fault as Karyn’s, the Slovers say, a consequence of marrying too young. “I don’t think either one of them was mature enough to be married. I think it takes two to make a marriage, and it takes two to mess it up,” Jeanette says. But even after the kids’ divorce, Jeanette says she and Mike still considered themselves part of Karyn’s family, albeit in a different way. “One time she said she felt kinda funny bringing Kolten to her ex-in-laws to be babysat every day. I told her not to think of me as an ex-in-law,” Jeanette says. “I told her think of me as Kolten’s grandmother.”

By all accounts, Karyn Hearn Slover was a charming young woman. “Bubbly” is the adjective most people reach for to describe her. “Beautiful” is another.

Michael met her at Richland Community College. Even though they were each dating other people, they got together during a car show, when she rode along in his yellow-and-white 1955 Chevy. The decision to get married was quick and almost casual. “We had a lot of fun, and it was just kinda like ‘Let’s get married!’ — kind of jokingly,” Michael says. “I produced a ring, and she’d put it on when she left the house and take it off when she got home.”

The Slovers say that Karyn’s parents weren’t happy about her relationship with Michael. Larry and Donna Hearn have professional careers; Mike Slover was a pipe insulator at the Clinton power plant and Jeanette, at that time, worked at a drive-through liquor store. “Oh, they definitely thought they were a whole lot better than the Slover family — and they definitely thought Michael was not the material they wanted for a son-in-law, believe me,” Jeanette says. How does she know? “Because Karyn told me,” she says. The Slovers say that Karyn didn’t find the courage to tell her parents that she was engaged until after she was pregnant. She and Michael pushed their planned wedding date up and married in January 1993. Kolten was born about seven months later, and Karyn went back to work when he was just 3 days old, leaving the baby with Jeanette. “Karyn liked to work. She liked being around people,” Jeanette says. Karyn worked at a J.C. Penney portrait studio, at a Decatur radio station, and with a temp agency before taking an advertising-sales position with the Decatur Herald & Review. Michael worked as an insulator, then took a job driving a truck for a Springfield 7Up distributor. He says that Karyn complained that he was gone too much. Her friends would later testify that he had slapped and shoved her. All of these problems, combined with financial worries, took a toll on their relationship. One night, when he was too tired to go out dancing with another couple as they had planned, he told her to go ahead without him. Someone from the nightclub called him and told him that he needed to come see what his wife was doing — dancing and smooching with another man. “That’s when I knew we had some major problems,” Michael says. “After that, it was all downhill.”

In the midst of divorce proceedings, Michael realized that he was going to have to pay for Kolten’s childcare, so he came up with the notion that his mom should continue babysitting for free. “I was a father looking at losing contact with my son, just getting to see him every other weekend, so my best solution was ‘Hey, my mom’s a free babysitter — there’s no reason to take him anywhere else.’ Karyn got along with my mom, so why should we pay for somebody when my mom could continue to watch him and I could go over and see him anytime I want?”

Karyn signed a divorce decree specifying that Jeanette would babysit Kolten until he started kindergarten.

That clause would be used against the Slovers — proof, prosecutors said, that the Slovers were obsessed with Kolten and therefore willing to murder Karyn.

It’s a theory the Slovers say that makes no sense. For one thing, Karyn seemed to appreciate having such a flexible child-care arrangement. Mary, who earned a degree in special education, criticized both Karyn and Michael for not spending enough time with Kolten, before and after the divorce “I did say [Karyn] wasn’t a good mother,” Mary admits. “I also said Michael wasn’t a good father. They were both so involved in their own lives that they were both quite content to just leave Kolten with my parents for hours and sometimes days at a time.”

It wasn’t unusual for Karyn to go grocery shopping after work, and want time to put the groceries away without a toddler underfoot. Then she might call and say, “I’m sure Kolten’s sleepy by now,” and just leave him with the Slovers overnight, Mary says. Karyn apologized for not picking Kolten up on time, but Jeanette assured her that it wasn’t a problem. “I had told her if I had anything special to do, I’d let her know, and not to worry about it because I knew her job wasn’t a 9-to-5 job,” Jeanette recalls. “I didn’t want her feeling like she had to rush.”

Furthermore, Karyn couldn’t afford to pay for childcare. In the years after her death, as the Slovers tried to divine what had happened, Jeanette and Mike discovered that Karyn had been “borrowing” money from both of them. “Karyn never had any money,” Mike says. “Apparently Jeanette was lending her money once in a while, I was giving her some money once in a while, and then it turns out that she didn’t even have any electricity to her house when this happened. We found all this out while sitting in the county jail.”

The modeling job in Georgia, made to sound so glamorous by the prosecution, wasn’t a permanent gig. It was a few days’ worth of work with the Savannah-based Paris World International agency — the kind of operation that requires girls to pay ($92, in Karyn’s case) to be listed on their Web site. The agency offered a discount to models who already had work lined up, but Karyn didn’t qualify. At the Slovers’ trial, the agency owner couldn’t recall what type of work Karyn would supposedly have been doing. But whatever it was, Jeanette figures, Karyn would have needed someone to watch Kolten. “I could very well see Karyn asking me to babysit and keep him those three days while she went out of town to do this job,” Jeanette says.

The question of whether Karyn would rather have Kolten with her as she ran errands or leave him with his grandmother became the linchpin of the murder trial.

The prosecution and the defense agreed that Karyn left work on Sept. 27, 1996, a Friday evening, intending to shop for a dress to wear to a wedding the next night. Her boyfriend, David Swann, a groomsman, was attending the rehearsal dinner that night. Karyn was driving his car, a black Pontiac Bonneville with personalized license plates reading “CADS7.”

At 9:57 p.m., the car was found abandoned on the shoulder of Interstate 72 — engine running, lights on, driver’s door open, Karyn’s purse still inside. The time between Karyn’s departure from work and the car’s discovery is the crux of the case. The prosecution asserts that Karyn went to the Slovers’ house to pick up Kolten, intending to take him shopping with her. Mary finds that idea absurd: “She wouldn’t go to the grocery store with Kolten. She certainly wasn’t going to go try on dresses with him.”

In the early days of the investigation, when police were asking the public to report any sightings of the black Bonneville with CADS7 plates, about a dozen motorists said they’d seen the car speeding along back roads between Decatur and Champaign, through Cerro Gordo. Other witnesses reported hearing gunshots and a chainsaw in Cerro Gordo. There were no reports from anyone claiming to have seen Karyn in Mount Zion that day and no reports of gunshots or the sound of a power saw. The Slovers say that Karyn didn’t pick Kolten up on Sept. 27. Jeanette took Kolten to Kmart, then to the car lot to pick up Mike for dinner at McDonald’s around 8. Before they got to McDonald’s, Kolten fell asleep, so they went home. Mike was watching Are You Being Served? when the phone rang a little after 10 p.m. “I heard Jeanette say, ‘Larry? What’s wrong?’ and I thought she was talking to my brother Larry, who lives in St. Louis. So I got up and jumped on the extension phone right away,” Mike says. “I heard all kinds of sobbing and crying.”

It was Larry Hearn, Karyn’s father. He had just gotten a call from Swann, who had been contacted by police about the abandoned car. Larry was relieved to learn that Kolten was with the Slovers, but distressed about what might have happened to Karyn. Jeanette was also worried. “I was concerned that something was wrong with the car and she’d got out and walked,” she says, voice choking on the memory. “I was concerned about a beautiful young lady being out on the road by herself, yes, I was.”

She immediately called Ronnie’s, the bar where Michael Jr. worked as a bouncer. Co-workers testified that he took the phone outside and was crying when he came back in. Two days later, a couple fishing near Findlay Marina found a trash bag containing a human head. Other remains were discovered the next day, some as late as Oct. 5 — the same day as Karyn’s funeral. “You’ve heard that expression ‘blew my mind’? I couldn’t believe it. I still can’t believe it,” Jeanette says. “How could anybody do something like that to a human being?”

The community of Decatur had the same reaction. This crime was incomprehensibly horrific. Whoever committed it had to be found and punished.

Decatur police interviewed Mike Slover on Oct. 9, and, aided by the Illinois State Police, searched the Slovers’ home and Miracle Motors a few days later. Mike admits that he owned a chainsaw but says that it wasn’t working and remembers that the cops gave it only a cursory check. “They could see it hadn’t been used in years. It hadn’t even been started in years. I was the type of guy that would never throw anything away. . . . I was always gonna get it fixed,” Mike says. “They didn’t even take it during the first search.”

At that point, investigators seemed more interested in Karyn’s most recent romantic relationships — Swann, a man named Brian Maxey, and Michael Jr. Michael had a solid alibi: He was working three jobs the evening Karyn disappeared — security manager at Cub Foods, where he had stayed late after catching a shoplifter; private karate instructor to a pair of students; and doorman at Ronnie’s. But the cops eventually ruled out Swann and Maxey as suspects and seemed to zero in on the Slover family. On Feb. 6, 1997, a swarm of investigators descended on their home and disassembled the plumbing, pulled up carpeting, and peeled paneling off the walls. “They covered up the windows with black plastic bags and Luminoled the walls and the floors,” Mike recalls. “That’s when we knew that they really suspected us.”

The investigators conducted a similar search the same day at Miracle Motors, this time seizing that rusty chainsaw. The car lot office lacked running water, making it unlikely that the family could have cleaned up a crime scene. Prosecutors would later suggest that Karyn was killed outside, and the evidence destroyed when Michael Jr. trimmed the weeds a few days later. The Slovers all say he cut the weeds on Oct. 1 as a birthday present to his father, who had received several citations from Mount Zion authorities ordering him to clean up the lot. Police also seized Mike’s gun collection — about a dozen firearms, some antiques — and all of his ammunition. Nothing matched. In addition to forensic tests, the family members went through questioning. They testified before the Macon County grand jury; Michael Jr. passed two polygraph tests. “I think we were very cooperative — at first.” Jeanette says. “But, you know, when you answer and re-answer and re-answer, you get to a point where you know they don’t care what you’ve got to say.” When Michael Jr. was called back to the grand jury on Jan. 26, 2000, he took the Fifth Amendment in response to every question. Indictments came down the next day.

During this time, Mary says, Michael was adjusting to his new role as the only parent Kolten had left. She helped Michael figure out how to tell Kolten that Karyn was gone, and they opted for the briefest explanation. “He didn’t need to know anything other than his mother had died and gone to heaven,” Mary says.

But the Hearns wanted Kolten to know a bit more, Mary recalls, and the issue became a source of tension between the two families. Michael started resisting the Hearns’ requests for impromptu visits with Kolten, and they responded by increasing their requests. The Hearns obtained a court order guaranteeing visitation rights with Kolten, and would arrive for these visits with a police escort. On the advice of Kolten’s therapist, Michael got a court order specifying that Kolten couldn’t stay overnight with the Hearns.

“I know they had a terrible loss,” Mary says, “but so did Kolten, and Michael had to try to figure out how to deal with that. Being that concerned and involved was new to him, so this was a period of real adjustment for him, too.”

At first, the Slovers tried to ignore what they considered minor indignities perpetrated by zealous investigators — like the brand-new carpet runners, still encased in plastic with sales tags attached, that police seized during the February 1997 search of their home. The Slovers can only speculate what evidentiary value rugs purchased months after Karyn’s death might have held.

“To make it look like they were carrying something out?” Jeanette guesses. “Just out of meanness,” Mike supposes. But as the investigation intensified, so did the affronts. After exhuming Karyn’s remains in July 1997 to examine buttons and rivets on her clothing, a team of Illinois investigators supervised by a Canadian forensics analyst, Dick Munroe, took over the Slovers’ car lot in March 1998 to conduct what they called an “archaeological dig.” Some of the cops doing the digging were shown what kind of buttons to look for, and, sure enough, when they sifted the buckets of excavated earth, they found metal buttons and rivets that matched the jeans Karyn had been wearing, as well as one white cloth-covered button consistent with the button on the cuff of her blouse. The Slovers offer two possible explanations for how these items came to be found on their car lot. The most logical one is that they came from clothing Mike removed from cars he was selling. A regular at the Decatur auto auction, he would buy cars costing maybe $300 or $400, spiff them up and sell them for $995. Many such vehicles came to the auction after being repossessed and therefore contained personal items belonging to the previous owners. Mike would throw the stuff in a barrel and burn it. The dig unearthed an array of fasteners, zippers, and clothing remnants. “Heck, I’ve found bowling balls, fishing rods, pagers, but all that stuff was no good to me,” he says. He hesitates to offer his second possible explanation — “It sounds paranoid,” he concedes — even though it’s the one he believes. “I know when these other guys in here say the police planted drugs on them, I’m thinking, ‘Man, police don’t do that’ . . . but apparently the police do do that, and they tried to do it to me with bones.”

On the morning of March 13, after the three-day “dig” at his car lot, Mike stopped by to “see how big of a mess they left.” He looked around the office, which was in shambles; then, on his way back to his car, he noticed a cardboard box from Foster’s meat market, sitting on top of a barrel. The box was full of bloody bones. “I’m kinda taken aback,” Mike recalls. “Are they trying to leave me a message? What is this about? I’m stumped.”

A day or so later, the lead investigator, Mike Mannix, called to arrange the return of a vehicle the forensics team had seized. When Mike met him at the car lot, Mannix asked nonchalantly whether he could retrieve “that box we left behind.”

“It was like a light bulb went off above my head,” Mike says. He told Mannix no, he couldn’t have the box. Then he called his attorney and asked him to send someone to take pictures of it. “There’s a police report that says they brought this box of bones to what they’re calling a crime scene and took a chainsaw and cut these bones up,” Mike says. “Their story is they did this to show the guys doing the digging what they’re looking for — little pieces of bone, or bone fragments.

“So why would they do that? I can understand ‘OK, you cut ’em up, here’s what you’re looking for.’ But why do that at the ‘crime scene’? Why not do that at the police station? There’s only one reason I can think of.”

The prosecution never introduced bone fragments into evidence at the Slovers’ trial, but Mannix told the grand jury that fragments had been found. The Decatur newspaper obtained a transcript of all the grand-jury testimony and published the “bone fragments” claim several times. The box from the meat market was never mentioned by the newspaper or during the trial.

By the spring of 1999, Mary had legally adopted Kolten. She says that she took this step so that she could sign his school and medical forms. It added weight, though, to the prosecution’s theory that the Slover family had an unhealthy obsession with Kolten, and it infuriated the Hearns, who were by then convinced of the Slovers’ guilt.

As the tensions between the families escalated, Mary and Michael Jr. decided to move to Hornbeak, Tenn., where Mary owned vacation property. But the cops followed. In the fall of 1999, officers from Illinois and Tennessee arrived at Mary’s house with a search warrant for fingerprints and hair samples. They handcuffed her, took her to the police station, and “ripped hunks of my hair out,” she says, then returned to rifle through her house. “I think it was all about intimidation,” she says. “All the time they were doing this, Michael and I were told we needed to come up with something they could use against our parents.”

Weeks later, the officers returned with another search warrant and ransacked the place. “Anything they could dump out onto the floor was dumped out onto the floor,” Mary says. “It looked like a tornado had been through the house.”

A few months later, after taking Kolten to Illinois to visit the Hearns, Mary returned to Hornbeak to find the door of her house standing open. There had been a fire in the basement — cause undetermined. During a subsequent visit to Illinois, Mary received a call from authorities in Hornbeak telling her that the house had burned again — this time to the ground. Mary believes that both fires were deliberately set, but she never pursued an investigation. “With everything else going on, it wasn’t a priority,” she says — because by then, her entire family had been arrested.

Though the Slovers stood accused of a barbarous crime, prosecutors backed off their original request for the death penalty. This decision came after the defense team received some $100,000 from the Capital Litigation Trust Fund — a fund established to provide capital defendants with well-paid attorneys and investigators. “De-deathing” the case meant that the family would be represented by public defenders. The Slovers hired a private attorney for Jeanette, but Mike isn’t sure that they got their money’s worth. “He kept calling Jeanette ‘Karyn,’ ” he says.

The trial lasted five weeks and featured several witnesses whose memories especially of Michael’s malice toward Karyn had “improved” significantly since they were first interviewed by police (one such witness was the stepdaughter of one of the prosecuting attorneys). Scientific evidence was presented by a dog-DNA expert, who testified that a hair found with Karyn’s remains came from one of the Slovers’ dogs, and Monroe — the Canadian forensics analyst — who testified that cinders and chunks of concrete found with Karyn’s remains came from Miracle Motors. The court’s refusal to allow the defense to use their own expert’s analysis to cross-examine Monroe was one of 14 issues the Slovers’ current attorney, John McCarthy of the Office of the State Appellate Defender, raised (and recently lost) on appeal. McCarthy has filed a petition for leave to appeal to the Illinois Supreme Court.

Although he declined to be interviewed, McCarthy last month sent Mike a letter recounting evidence police failed to adequately pursue — human hair found with Karyn’s remains and a fingerprint on Findlay Bridge over Lake Shelbyville, just inches from a smear of Karyn’s own blood. The coroner never even scraped under Karyn’s fingernails. “I am writing to let you know that I will continue to fight on your behalf. I still lose sleep over your conviction and the appellate court’s decision,” McCarthy wrote.

As adamant as the Slovers are about their innocence, they seem to spend their time tormenting themselves with guilt. Michael Jr. blames himself for driving Karyn away.

“If I’d been a better husband,” he says repeatedly, “she wouldn’t have gone out and met the people that she did, and she wouldn’t be dead.”

Jeanette blames herself for not alerting someone when Karyn failed to pick Kolten up. “I went over this and over this in my mind, but . . . I didn’t worry, I didn’t think ‘Oh, something is wrong,’ ” Jeanette says, her voice quivering. “She had been as late as 8 before, so I thought, ‘Oh, she’s just running a little later.’ ”

As the patriarch of the family, Mike blames himself for allowing his wife and son to reject an offer to walk free if they’d pleaded guilty to concealing a homicide and he’d pleaded guilty to the murder. “If I knew then what I know now, I would’ve forced them to take it,” he says. “Now that I know a lot more about the legal system, when you make a deal like that with the prosecutor, it doesn’t mean you actually did it; it just means that you don’t want to run the risk of going through a trial and being sentenced to basically life in prison.”

The family’s main concern is Kolten, who has lived with the Hearns since a Macon County judge terminated Mary’s parental rights. Michael Jr. — whom prosecutors described as a “tough guy” — breaks down when asked about his son. “I’d like to tell him that we didn’t do it, that we didn’t kill his mom, that I love him and I miss him very much,” he sobs. Mary has her own remorse about aggravating the tug-of-war over Kolten. “Both sides could have handled things better,” she admits, “but it’s a pretty big leap from two parties having a disagreement about visitation to saying [my family] was involved in killing Karyn.”

Her biggest regret, though, is that the posthumous struggle supplied the motive a jury needed to convict her family of murder. “They didn’t do it — but there’s someone out there who did,” Mary says. “Part of what’s so horrible about this isn’t just that they destroyed my family, it’s that someone got away with doing this to Karyn.”

During the years between Karyn’s murder in September 1996 and the Slovers’ arrest in January 2000, the family didn’t talk to the media. At their trial, a court reporter read their grand-jury testimony into the record; the Slovers’ attorneys advised them not to take the stand. They’ve never before told their side of the story. Denise Ambrose, the attorney handling the Slovers’ case at the Office of the State Appellate Prosecutor, declined to comment. Richard Current, Macon County first assistant state’s attorney refused to answer any questions for this article and said he was also speaking on behalf of state’s attorney Jack Ahola as well as the lead investigator in the case, Mike Mannix, and Karyn’s parents, Larry and Donna Hearn.

To interview the Slover family, one must spend days driving several hundred miles in different directions. Jeanette is in the Dwight Correctional Center, 125 miles northeast of Springfield; Michael Jr., is in the Menard Correctional Center, 150 miles southwest of here. Michael Sr., called Mike by the family, was in Statesville, at Joliet, but was transferred to Pontiac, about 100 miles northeast of Springfield, in December.

Mary visits them as often as she can — her brother twice a month, her parents every six weeks. The separation from one another is the worst part of their punishment. Whatever else anybody thinks of them, they are a tight family. Mike and Jeanette grew up next door to each other in St. Louis, married young, and maintained a relationship so close that their kids took pride in it. “Mom and Dad enjoyed each other’s company,” Michael Jr. says. “It’s more than just husband and wife; they are friends.”

That closeness was a factor in their downfall. Content with each other, they didn’t have many friends. They didn’t belong to any social clubs, weren’t regulars at any church or any tavern. On the night Karyn disappeared — Sept. 27, 1996 — they say they were home watching a British comedy. They were each other’s alibi. In fact, prosecutors say the Slovers’ familial bond was so intense that it became sinister. According to their theory, Karyn — an aspiring model — received a temporary job offer from a Georgia-based modeling agency. The Slovers killed her that very day because they were afraid that she would take Kolten, then 3 years old, and move out of state. Considering that premise, it’s surprising to discover how much affection the Slovers seem to have had for Karyn. Asked open-ended questions — what was Karyn like? — they offer fond anecdotes. “One time, we’re lying in bed and she just all the sudden turns to me and said, ‘What would happen if I ran out of dishwasher detergent and I just put some liquid stuff in there?’ And I said, ‘Man, there would probably be soap bubbles everywhere!’ ” Michael recalls. “She jumps up and runs into the kitchen, and I hear ‘Michael? Can you come in here?’ There were soap bubbles all across the floor. She kept you laughing,” he says. “She was funny. She was constantly doing stuff like that.”

Their divorce was as much Michael’s fault as Karyn’s, the Slovers say, a consequence of marrying too young. “I don’t think either one of them was mature enough to be married. I think it takes two to make a marriage, and it takes two to mess it up,” Jeanette says. But even after the kids’ divorce, Jeanette says she and Mike still considered themselves part of Karyn’s family, albeit in a different way. “One time she said she felt kinda funny bringing Kolten to her ex-in-laws to be babysat every day. I told her not to think of me as an ex-in-law,” Jeanette says. “I told her think of me as Kolten’s grandmother.”

By all accounts, Karyn Hearn Slover was a charming young woman. “Bubbly” is the adjective most people reach for to describe her. “Beautiful” is another.

Michael met her at Richland Community College. Even though they were each dating other people, they got together during a car show, when she rode along in his yellow-and-white 1955 Chevy. The decision to get married was quick and almost casual. “We had a lot of fun, and it was just kinda like ‘Let’s get married!’ — kind of jokingly,” Michael says. “I produced a ring, and she’d put it on when she left the house and take it off when she got home.”

The Slovers say that Karyn’s parents weren’t happy about her relationship with Michael. Larry and Donna Hearn have professional careers; Mike Slover was a pipe insulator at the Clinton power plant and Jeanette, at that time, worked at a drive-through liquor store. “Oh, they definitely thought they were a whole lot better than the Slover family — and they definitely thought Michael was not the material they wanted for a son-in-law, believe me,” Jeanette says. How does she know? “Because Karyn told me,” she says. The Slovers say that Karyn didn’t find the courage to tell her parents that she was engaged until after she was pregnant. She and Michael pushed their planned wedding date up and married in January 1993. Kolten was born about seven months later, and Karyn went back to work when he was just 3 days old, leaving the baby with Jeanette. “Karyn liked to work. She liked being around people,” Jeanette says. Karyn worked at a J.C. Penney portrait studio, at a Decatur radio station, and with a temp agency before taking an advertising-sales position with the Decatur Herald & Review. Michael worked as an insulator, then took a job driving a truck for a Springfield 7Up distributor. He says that Karyn complained that he was gone too much. Her friends would later testify that he had slapped and shoved her. All of these problems, combined with financial worries, took a toll on their relationship. One night, when he was too tired to go out dancing with another couple as they had planned, he told her to go ahead without him. Someone from the nightclub called him and told him that he needed to come see what his wife was doing — dancing and smooching with another man. “That’s when I knew we had some major problems,” Michael says. “After that, it was all downhill.”

In the midst of divorce proceedings, Michael realized that he was going to have to pay for Kolten’s childcare, so he came up with the notion that his mom should continue babysitting for free. “I was a father looking at losing contact with my son, just getting to see him every other weekend, so my best solution was ‘Hey, my mom’s a free babysitter — there’s no reason to take him anywhere else.’ Karyn got along with my mom, so why should we pay for somebody when my mom could continue to watch him and I could go over and see him anytime I want?”

Karyn signed a divorce decree specifying that Jeanette would babysit Kolten until he started kindergarten.

That clause would be used against the Slovers — proof, prosecutors said, that the Slovers were obsessed with Kolten and therefore willing to murder Karyn.

It’s a theory the Slovers say that makes no sense. For one thing, Karyn seemed to appreciate having such a flexible child-care arrangement. Mary, who earned a degree in special education, criticized both Karyn and Michael for not spending enough time with Kolten, before and after the divorce “I did say [Karyn] wasn’t a good mother,” Mary admits. “I also said Michael wasn’t a good father. They were both so involved in their own lives that they were both quite content to just leave Kolten with my parents for hours and sometimes days at a time.”

It wasn’t unusual for Karyn to go grocery shopping after work, and want time to put the groceries away without a toddler underfoot. Then she might call and say, “I’m sure Kolten’s sleepy by now,” and just leave him with the Slovers overnight, Mary says. Karyn apologized for not picking Kolten up on time, but Jeanette assured her that it wasn’t a problem. “I had told her if I had anything special to do, I’d let her know, and not to worry about it because I knew her job wasn’t a 9-to-5 job,” Jeanette recalls. “I didn’t want her feeling like she had to rush.”

Furthermore, Karyn couldn’t afford to pay for childcare. In the years after her death, as the Slovers tried to divine what had happened, Jeanette and Mike discovered that Karyn had been “borrowing” money from both of them. “Karyn never had any money,” Mike says. “Apparently Jeanette was lending her money once in a while, I was giving her some money once in a while, and then it turns out that she didn’t even have any electricity to her house when this happened. We found all this out while sitting in the county jail.”

The modeling job in Georgia, made to sound so glamorous by the prosecution, wasn’t a permanent gig. It was a few days’ worth of work with the Savannah-based Paris World International agency — the kind of operation that requires girls to pay ($92, in Karyn’s case) to be listed on their Web site. The agency offered a discount to models who already had work lined up, but Karyn didn’t qualify. At the Slovers’ trial, the agency owner couldn’t recall what type of work Karyn would supposedly have been doing. But whatever it was, Jeanette figures, Karyn would have needed someone to watch Kolten. “I could very well see Karyn asking me to babysit and keep him those three days while she went out of town to do this job,” Jeanette says.

The question of whether Karyn would rather have Kolten with her as she ran errands or leave him with his grandmother became the linchpin of the murder trial.

The prosecution and the defense agreed that Karyn left work on Sept. 27, 1996, a Friday evening, intending to shop for a dress to wear to a wedding the next night. Her boyfriend, David Swann, a groomsman, was attending the rehearsal dinner that night. Karyn was driving his car, a black Pontiac Bonneville with personalized license plates reading “CADS7.”

At 9:57 p.m., the car was found abandoned on the shoulder of Interstate 72 — engine running, lights on, driver’s door open, Karyn’s purse still inside. The time between Karyn’s departure from work and the car’s discovery is the crux of the case. The prosecution asserts that Karyn went to the Slovers’ house to pick up Kolten, intending to take him shopping with her. Mary finds that idea absurd: “She wouldn’t go to the grocery store with Kolten. She certainly wasn’t going to go try on dresses with him.”

In the early days of the investigation, when police were asking the public to report any sightings of the black Bonneville with CADS7 plates, about a dozen motorists said they’d seen the car speeding along back roads between Decatur and Champaign, through Cerro Gordo. Other witnesses reported hearing gunshots and a chainsaw in Cerro Gordo. There were no reports from anyone claiming to have seen Karyn in Mount Zion that day and no reports of gunshots or the sound of a power saw. The Slovers say that Karyn didn’t pick Kolten up on Sept. 27. Jeanette took Kolten to Kmart, then to the car lot to pick up Mike for dinner at McDonald’s around 8. Before they got to McDonald’s, Kolten fell asleep, so they went home. Mike was watching Are You Being Served? when the phone rang a little after 10 p.m. “I heard Jeanette say, ‘Larry? What’s wrong?’ and I thought she was talking to my brother Larry, who lives in St. Louis. So I got up and jumped on the extension phone right away,” Mike says. “I heard all kinds of sobbing and crying.”

It was Larry Hearn, Karyn’s father. He had just gotten a call from Swann, who had been contacted by police about the abandoned car. Larry was relieved to learn that Kolten was with the Slovers, but distressed about what might have happened to Karyn. Jeanette was also worried. “I was concerned that something was wrong with the car and she’d got out and walked,” she says, voice choking on the memory. “I was concerned about a beautiful young lady being out on the road by herself, yes, I was.”

She immediately called Ronnie’s, the bar where Michael Jr. worked as a bouncer. Co-workers testified that he took the phone outside and was crying when he came back in. Two days later, a couple fishing near Findlay Marina found a trash bag containing a human head. Other remains were discovered the next day, some as late as Oct. 5 — the same day as Karyn’s funeral. “You’ve heard that expression ‘blew my mind’? I couldn’t believe it. I still can’t believe it,” Jeanette says. “How could anybody do something like that to a human being?”

The community of Decatur had the same reaction. This crime was incomprehensibly horrific. Whoever committed it had to be found and punished.

Decatur police interviewed Mike Slover on Oct. 9, and, aided by the Illinois State Police, searched the Slovers’ home and Miracle Motors a few days later. Mike admits that he owned a chainsaw but says that it wasn’t working and remembers that the cops gave it only a cursory check. “They could see it hadn’t been used in years. It hadn’t even been started in years. I was the type of guy that would never throw anything away. . . . I was always gonna get it fixed,” Mike says. “They didn’t even take it during the first search.”

At that point, investigators seemed more interested in Karyn’s most recent romantic relationships — Swann, a man named Brian Maxey, and Michael Jr. Michael had a solid alibi: He was working three jobs the evening Karyn disappeared — security manager at Cub Foods, where he had stayed late after catching a shoplifter; private karate instructor to a pair of students; and doorman at Ronnie’s. But the cops eventually ruled out Swann and Maxey as suspects and seemed to zero in on the Slover family. On Feb. 6, 1997, a swarm of investigators descended on their home and disassembled the plumbing, pulled up carpeting, and peeled paneling off the walls. “They covered up the windows with black plastic bags and Luminoled the walls and the floors,” Mike recalls. “That’s when we knew that they really suspected us.”

The investigators conducted a similar search the same day at Miracle Motors, this time seizing that rusty chainsaw. The car lot office lacked running water, making it unlikely that the family could have cleaned up a crime scene. Prosecutors would later suggest that Karyn was killed outside, and the evidence destroyed when Michael Jr. trimmed the weeds a few days later. The Slovers all say he cut the weeds on Oct. 1 as a birthday present to his father, who had received several citations from Mount Zion authorities ordering him to clean up the lot. Police also seized Mike’s gun collection — about a dozen firearms, some antiques — and all of his ammunition. Nothing matched. In addition to forensic tests, the family members went through questioning. They testified before the Macon County grand jury; Michael Jr. passed two polygraph tests. “I think we were very cooperative — at first.” Jeanette says. “But, you know, when you answer and re-answer and re-answer, you get to a point where you know they don’t care what you’ve got to say.” When Michael Jr. was called back to the grand jury on Jan. 26, 2000, he took the Fifth Amendment in response to every question. Indictments came down the next day.

During this time, Mary says, Michael was adjusting to his new role as the only parent Kolten had left. She helped Michael figure out how to tell Kolten that Karyn was gone, and they opted for the briefest explanation. “He didn’t need to know anything other than his mother had died and gone to heaven,” Mary says.

But the Hearns wanted Kolten to know a bit more, Mary recalls, and the issue became a source of tension between the two families. Michael started resisting the Hearns’ requests for impromptu visits with Kolten, and they responded by increasing their requests. The Hearns obtained a court order guaranteeing visitation rights with Kolten, and would arrive for these visits with a police escort. On the advice of Kolten’s therapist, Michael got a court order specifying that Kolten couldn’t stay overnight with the Hearns.

“I know they had a terrible loss,” Mary says, “but so did Kolten, and Michael had to try to figure out how to deal with that. Being that concerned and involved was new to him, so this was a period of real adjustment for him, too.”

At first, the Slovers tried to ignore what they considered minor indignities perpetrated by zealous investigators — like the brand-new carpet runners, still encased in plastic with sales tags attached, that police seized during the February 1997 search of their home. The Slovers can only speculate what evidentiary value rugs purchased months after Karyn’s death might have held.

“To make it look like they were carrying something out?” Jeanette guesses. “Just out of meanness,” Mike supposes. But as the investigation intensified, so did the affronts. After exhuming Karyn’s remains in July 1997 to examine buttons and rivets on her clothing, a team of Illinois investigators supervised by a Canadian forensics analyst, Dick Munroe, took over the Slovers’ car lot in March 1998 to conduct what they called an “archaeological dig.” Some of the cops doing the digging were shown what kind of buttons to look for, and, sure enough, when they sifted the buckets of excavated earth, they found metal buttons and rivets that matched the jeans Karyn had been wearing, as well as one white cloth-covered button consistent with the button on the cuff of her blouse. The Slovers offer two possible explanations for how these items came to be found on their car lot. The most logical one is that they came from clothing Mike removed from cars he was selling. A regular at the Decatur auto auction, he would buy cars costing maybe $300 or $400, spiff them up and sell them for $995. Many such vehicles came to the auction after being repossessed and therefore contained personal items belonging to the previous owners. Mike would throw the stuff in a barrel and burn it. The dig unearthed an array of fasteners, zippers, and clothing remnants. “Heck, I’ve found bowling balls, fishing rods, pagers, but all that stuff was no good to me,” he says. He hesitates to offer his second possible explanation — “It sounds paranoid,” he concedes — even though it’s the one he believes. “I know when these other guys in here say the police planted drugs on them, I’m thinking, ‘Man, police don’t do that’ . . . but apparently the police do do that, and they tried to do it to me with bones.”

On the morning of March 13, after the three-day “dig” at his car lot, Mike stopped by to “see how big of a mess they left.” He looked around the office, which was in shambles; then, on his way back to his car, he noticed a cardboard box from Foster’s meat market, sitting on top of a barrel. The box was full of bloody bones. “I’m kinda taken aback,” Mike recalls. “Are they trying to leave me a message? What is this about? I’m stumped.”

A day or so later, the lead investigator, Mike Mannix, called to arrange the return of a vehicle the forensics team had seized. When Mike met him at the car lot, Mannix asked nonchalantly whether he could retrieve “that box we left behind.”

“It was like a light bulb went off above my head,” Mike says. He told Mannix no, he couldn’t have the box. Then he called his attorney and asked him to send someone to take pictures of it. “There’s a police report that says they brought this box of bones to what they’re calling a crime scene and took a chainsaw and cut these bones up,” Mike says. “Their story is they did this to show the guys doing the digging what they’re looking for — little pieces of bone, or bone fragments.

“So why would they do that? I can understand ‘OK, you cut ’em up, here’s what you’re looking for.’ But why do that at the ‘crime scene’? Why not do that at the police station? There’s only one reason I can think of.”

The prosecution never introduced bone fragments into evidence at the Slovers’ trial, but Mannix told the grand jury that fragments had been found. The Decatur newspaper obtained a transcript of all the grand-jury testimony and published the “bone fragments” claim several times. The box from the meat market was never mentioned by the newspaper or during the trial.

By the spring of 1999, Mary had legally adopted Kolten. She says that she took this step so that she could sign his school and medical forms. It added weight, though, to the prosecution’s theory that the Slover family had an unhealthy obsession with Kolten, and it infuriated the Hearns, who were by then convinced of the Slovers’ guilt.

As the tensions between the families escalated, Mary and Michael Jr. decided to move to Hornbeak, Tenn., where Mary owned vacation property. But the cops followed. In the fall of 1999, officers from Illinois and Tennessee arrived at Mary’s house with a search warrant for fingerprints and hair samples. They handcuffed her, took her to the police station, and “ripped hunks of my hair out,” she says, then returned to rifle through her house. “I think it was all about intimidation,” she says. “All the time they were doing this, Michael and I were told we needed to come up with something they could use against our parents.”

Weeks later, the officers returned with another search warrant and ransacked the place. “Anything they could dump out onto the floor was dumped out onto the floor,” Mary says. “It looked like a tornado had been through the house.”

A few months later, after taking Kolten to Illinois to visit the Hearns, Mary returned to Hornbeak to find the door of her house standing open. There had been a fire in the basement — cause undetermined. During a subsequent visit to Illinois, Mary received a call from authorities in Hornbeak telling her that the house had burned again — this time to the ground. Mary believes that both fires were deliberately set, but she never pursued an investigation. “With everything else going on, it wasn’t a priority,” she says — because by then, her entire family had been arrested.

Though the Slovers stood accused of a barbarous crime, prosecutors backed off their original request for the death penalty. This decision came after the defense team received some $100,000 from the Capital Litigation Trust Fund — a fund established to provide capital defendants with well-paid attorneys and investigators. “De-deathing” the case meant that the family would be represented by public defenders. The Slovers hired a private attorney for Jeanette, but Mike isn’t sure that they got their money’s worth. “He kept calling Jeanette ‘Karyn,’ ” he says.

The trial lasted five weeks and featured several witnesses whose memories especially of Michael’s malice toward Karyn had “improved” significantly since they were first interviewed by police (one such witness was the stepdaughter of one of the prosecuting attorneys). Scientific evidence was presented by a dog-DNA expert, who testified that a hair found with Karyn’s remains came from one of the Slovers’ dogs, and Monroe — the Canadian forensics analyst — who testified that cinders and chunks of concrete found with Karyn’s remains came from Miracle Motors. The court’s refusal to allow the defense to use their own expert’s analysis to cross-examine Monroe was one of 14 issues the Slovers’ current attorney, John McCarthy of the Office of the State Appellate Defender, raised (and recently lost) on appeal. McCarthy has filed a petition for leave to appeal to the Illinois Supreme Court.

Although he declined to be interviewed, McCarthy last month sent Mike a letter recounting evidence police failed to adequately pursue — human hair found with Karyn’s remains and a fingerprint on Findlay Bridge over Lake Shelbyville, just inches from a smear of Karyn’s own blood. The coroner never even scraped under Karyn’s fingernails. “I am writing to let you know that I will continue to fight on your behalf. I still lose sleep over your conviction and the appellate court’s decision,” McCarthy wrote.

As adamant as the Slovers are about their innocence, they seem to spend their time tormenting themselves with guilt. Michael Jr. blames himself for driving Karyn away.

“If I’d been a better husband,” he says repeatedly, “she wouldn’t have gone out and met the people that she did, and she wouldn’t be dead.”

Jeanette blames herself for not alerting someone when Karyn failed to pick Kolten up. “I went over this and over this in my mind, but . . . I didn’t worry, I didn’t think ‘Oh, something is wrong,’ ” Jeanette says, her voice quivering. “She had been as late as 8 before, so I thought, ‘Oh, she’s just running a little later.’ ”

As the patriarch of the family, Mike blames himself for allowing his wife and son to reject an offer to walk free if they’d pleaded guilty to concealing a homicide and he’d pleaded guilty to the murder. “If I knew then what I know now, I would’ve forced them to take it,” he says. “Now that I know a lot more about the legal system, when you make a deal like that with the prosecutor, it doesn’t mean you actually did it; it just means that you don’t want to run the risk of going through a trial and being sentenced to basically life in prison.”

The family’s main concern is Kolten, who has lived with the Hearns since a Macon County judge terminated Mary’s parental rights. Michael Jr. — whom prosecutors described as a “tough guy” — breaks down when asked about his son. “I’d like to tell him that we didn’t do it, that we didn’t kill his mom, that I love him and I miss him very much,” he sobs. Mary has her own remorse about aggravating the tug-of-war over Kolten. “Both sides could have handled things better,” she admits, “but it’s a pretty big leap from two parties having a disagreement about visitation to saying [my family] was involved in killing Karyn.”

Her biggest regret, though, is that the posthumous struggle supplied the motive a jury needed to convict her family of murder. “They didn’t do it — but there’s someone out there who did,” Mary says. “Part of what’s so horrible about this isn’t just that they destroyed my family, it’s that someone got away with doing this to Karyn.”

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!