Grave robbers and academics

Fascinating book recounts the struggle for rich cache of Indian artifacts

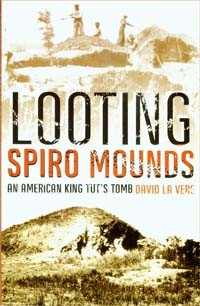

Looting Spiro Mounds: An American King Tut’s Tomb

By David LaVere, 2007, University of Oklahoma Press, 2007, 255 pages, paperback, $24.95

[

{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 1",

"component": "11490391",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 2",

"component": "11490392",

"insertPoint": "7",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

},{

"name": "Air - MedRect Combo - Inline Content 3",

"component": "11490393",

"insertPoint": "12",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block"

}

]

Untitled Document

The subtitle of David LaVere’s Looting Spiro Mounds is a

footnote to perhaps the greatest public grave robbery in history: Howard

Carter’s 1924 discovery, opening, and emptying of King

Tutankhamun’s tomb in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. That story,

which ran in The Times of London and captured headlines around the world, legitimized

treasure hunting in ancient cemeteries and fueled the market for burial

antiquities, especially for American Indian artifacts in the United States.

Here in the Midwest, grave goods from Cahokia Mounds

and other prehistoric sites around the country have made their way into

some of the largest private collections in the world. When Edward W. Payne

— a Springfield banker, real-estate investor, and board member of the

Illinois State Historical Society — died, in 1932, he had amassed

what many consider the largest collection of Indian artifacts in the world.

Valued at more than $3 million at the height of the Depression,

Payne’s collection was auctioned off in 1937 to pay his debts. Some

of the collection went to Dickson Mounds, in Lewistown, but much of it went

back into private hands.

Payne, another footnote in LaVere’s book, died one year before Spiro Mounds, a Mississippian mortuary site in northeastern Oklahoma, was “mined” for its riches, but in this case the treasure hunters made no pretense of collecting and protecting Native American history for posterity. What they found was an incredible cache of artifacts, including stunningly engraved seashells, beautiful copper plates and jewelry, pristine points and spearheads, thousands of pearl beads, and rare effigy pipes. Their goal — to find and sell ancient Indian relics for profit — was simple, and their Pocola Mining Co. operated fully within the law. The owners had legally leased the property on which the dozen mounds sat, and the miners went about their work vigorously with pick and shovel. There were no state or national laws at the time to prevent the “pot hunters,” as they are still euphemistically called, from digging into the mounds, and only University of Oklahoma professor Forrest E. Clements, chairman of the anthropology department, stood in their way. Clements had other plans for the artifacts. He wanted them collected, stored, and studied by anthropologists such as himself. Clements knew that the Spiro collection could put his university on the map and perhaps even make him famous. He favored excavation by professionals, not by pot hunters. Such is the plot of LaVere’s fascinating book, which presents the drama of these unlikely players as they struggle for control of the richest cache of Indian artifacts in modern history. To the author’s credit, neither Clements nor the pot hunters come off as villains, but neither are they heroes. Certainly there are no winners; whatever historical context that might have been uncovered at Spiro Mounds was forever destroyed. Contemporary archaeologists consider the looting of Spiro Mounds one of the great cultural crimes of the last century, though few today outside the profession even know of the site’s existence. Comparisons to King Tut and the Valley of the Kings are apt. The site rivals Cahokia Mounds in Collinsville, the largest Native American earthwork in North America, in complexity and significance, and it is that story, the piecing together of the all-but-obliterated history of an ancient city within the context of the Mississippian culture, that makes this such a good read. If there is one fault to this book, it’s that LaVere, a history professor at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, occasionally stretches the known history of the Mississippian culture from the factual to the speculative — but that’s forgivable, given the mystery of these forgotten people and the inscrutable nature of their artifacts. A little imagination is good for the spirits.

William Furry is the executive director of the Illinois State Historical Society and a former editor of Illinois Times.

Payne, another footnote in LaVere’s book, died one year before Spiro Mounds, a Mississippian mortuary site in northeastern Oklahoma, was “mined” for its riches, but in this case the treasure hunters made no pretense of collecting and protecting Native American history for posterity. What they found was an incredible cache of artifacts, including stunningly engraved seashells, beautiful copper plates and jewelry, pristine points and spearheads, thousands of pearl beads, and rare effigy pipes. Their goal — to find and sell ancient Indian relics for profit — was simple, and their Pocola Mining Co. operated fully within the law. The owners had legally leased the property on which the dozen mounds sat, and the miners went about their work vigorously with pick and shovel. There were no state or national laws at the time to prevent the “pot hunters,” as they are still euphemistically called, from digging into the mounds, and only University of Oklahoma professor Forrest E. Clements, chairman of the anthropology department, stood in their way. Clements had other plans for the artifacts. He wanted them collected, stored, and studied by anthropologists such as himself. Clements knew that the Spiro collection could put his university on the map and perhaps even make him famous. He favored excavation by professionals, not by pot hunters. Such is the plot of LaVere’s fascinating book, which presents the drama of these unlikely players as they struggle for control of the richest cache of Indian artifacts in modern history. To the author’s credit, neither Clements nor the pot hunters come off as villains, but neither are they heroes. Certainly there are no winners; whatever historical context that might have been uncovered at Spiro Mounds was forever destroyed. Contemporary archaeologists consider the looting of Spiro Mounds one of the great cultural crimes of the last century, though few today outside the profession even know of the site’s existence. Comparisons to King Tut and the Valley of the Kings are apt. The site rivals Cahokia Mounds in Collinsville, the largest Native American earthwork in North America, in complexity and significance, and it is that story, the piecing together of the all-but-obliterated history of an ancient city within the context of the Mississippian culture, that makes this such a good read. If there is one fault to this book, it’s that LaVere, a history professor at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, occasionally stretches the known history of the Mississippian culture from the factual to the speculative — but that’s forgivable, given the mystery of these forgotten people and the inscrutable nature of their artifacts. A little imagination is good for the spirits.

William Furry is the executive director of the Illinois State Historical Society and a former editor of Illinois Times.

Illinois Times has provided readers with independent journalism for almost 50 years, from news and politics to arts and culture.

Your support will help cover the costs of editorial content published each week. Without local news organizations, we would be less informed about the issues that affect our community..

Got something to say?

Send a letter to the editor and we'll publish your feedback in print!