It was the morning of Sept. 15, 2020. Jaala Smylie, 20 years old at the time, rented a room in her aunt's home on the west side of town. Smylie's aunt had woken up later than usual and didn't want to be late to work. She asked Smylie to take her 10-year-old son, Smylie's cousin, across town to day care on the north end, where he attended virtual school. Smylie didn't have to work that morning. So, still in her pajamas, she hopped in the car and took off.

At the same time, Springfield Police Officer Chance Warnisher was starting his work day. He was doing a traffic detail on Sixth Street between Ash Street and Stanford Avenue. It was just after 8 a.m. when he pulled Smylie over. Her young cousin sat next to her in the passenger seat. Within minutes, Smylie would be taken out of the car and forced onto the ground, surrounded by four police officers.

During the apprehension, Warnisher used his taser to "drive-stun" Smylie – a method meant to cause pain without fully incapacitating the person. Smylie subsequently lodged a complaint, which was investigated internally by the Springfield Police Department. The department mostly supported Warnisher's actions that day, based on the report summarizing its internal investigation. Police records obtained by Illinois Times through a public records request show Warnisher was exonerated of allegations brought forth by Smylie. But in a letter the police chief told Smylie that Warnisher's conduct was contrary to department policy. Police records also show Warnisher had a history of questionable interactions with citizens. Earlier in 2020, before arresting Smylie, he was disciplined for calling a suspect a "fucking dumb son of a bitch," among other vulgarities.

"How Black people get shot"

Warnisher, who is white, was listening to country music as he stopped his patrol car near the intersection of Sixth and Oak Streets, across from Iles Park. He walked up to the driver's side of Smylie's Dodge Dart. Smylie, who is Black, had her hair tied back in a scarf. She wore a sweatshirt, blue shorts and yellow Crocs with socks. As body camera footage showed, Smylie immediately handed the officer her driver's license. "Speed limit's 35, you were running 52," Warnisher said to her. Smylie started to disagree. "I was not going 52." Warnisher cut her off. "There's no arguing with me," he said.

Warnisher asked Smylie for proof of insurance. Then he immediately followed with, "Can you put it in park for me, so you don't run over me? Put the car in park please." Smylie responded, "Yes sir," and told him to wait a second. Later, she told the department's internal affairs unit that she was looking for her proof of insurance stored on her phone.

Warnisher asked her again to park the car, and then a third time. Smylie seemed distracted, with both hands on her phone. She had her mom on a call as she scrolled through it. She put the car in park. And then, within less than a minute of the two having met, Warnisher asked Smylie to exit the vehicle.

To her mother on the phone she said, "This man's trying to get me out of the car for no reason." Smylie told Warnisher she was trying to find her proof of insurance. Warnisher opened her door and told Smylie she must exit the car. He told her if she didn't, she would be arrested. He called for backup. He told Smylie that the law required her to get out of the car.

"This is how Black people get shot," she said, looking at her mother over video call. Smylie had never had as much as a traffic ticket before this moment. But it wasn't the first time she had interacted with the police.

"Absolutely wonderful"

Four months earlier, on June 6, 2020, a Saturday, Smylie organized a march and rally for Black lives in downtown Springfield. As she took to the microphone at the steps of the Abraham Lincoln statue outside the Statehouse, she made a point of thanking the police, some of whom were among the crowd that spring day.

"I see our police department," said Smylie. "They have been absolutely wonderful." She thanked them for "making sure we're not hit by any cars, and being patient with us even when we don't communicate well." She went on, "Thank you for being here and keeping us safe." People in the crowd clapped.

Smylie told Illinois Times during a phone interview the day after the June rally about going to Kansas for college on a basketball scholarship. She wanted to major in criminal justice but it didn't work out, so she came home to Springfield and began work as a caretaker. She decided to pursue a nursing degree. Smylie said the pandemic had only increased her desire to nurse and be on the front lines caring for people.

Smylie said the idea for the Saturday protest came to her when a family friend lamented not being able to make demonstrations that happened during weekdays. She quickly got to organizing a protest for the coming weekend. She wanted to take advantage of the energy of the Black Lives Matter movement. She said she suspected that the movement's resurgence might fizzle "until the next death."

Smylie was one of the original members of a group of Springfield young people formed over their shared passion for racial justice. By the time she helped plan the June rally, several thousand people had already demonstrated in Springfield to take a stand against the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis and police violence. Smylie said she didn't believe the answer for change was to defund police – she said she wanted more training and accountability.

After all the speakers were done addressing the crowd that June day, the event wrapped up with music over the sound system. Smylie said some bystanders accused those dancing of wanting to start a riot. Smylie said she assured them that "us celebrating and having fun is not violent." But what was there to celebrate? "We're celebrating change, because we know, although we're not seeing it right now, we know that things have to change. Because the people are demanding it," said Smylie.

"All this over a traffic stop"

"Mom, I'm not getting out till you get here," Smylie told her mother over video call during the September 2020 traffic stop. The backup Warnisher had called for arrived, including Officer Jamarae Davis. Warnisher asked him to go talk to Smylie. Smylie had brought up race. "So I thought she would be more comfortable talking to an African American officer," Warnisher later told internal affairs – the part of the Springfield Police Department that would investigate Smylie's complaints about Warnisher's conduct – according to interview transcripts obtained by Illinois Times.

Davis approached the vehicle. Smylie asked him if she could explain the situation and began to tell her side of the story. Footage from Davis's body camera appeared to show Warnisher in the background telling Davis to get Smylie out of the car within seconds of Davis approaching her vehicle. "There's too many lives being lost," she said. "You all are going to have to pull me out."

And that's what the officers did, as Smylie's young cousin cried out. Both Davis and Warnisher pulled on her arms. Another cop, Officer Mark Johnson, assisted them in taking her to the ground. During the incident, Warnisher claimed she hit him. "No I didn't hit you and you know I didn't," said Smylie, from the ground. And then she cried out, "Ow, why are you tasing me?" as Warnisher drive-stunned her.

Later, according to a police interview transcript, Johnson said, "She didn't seem loud to me at the time or a threat. She was just resisting his commands." In his police report about the incident, Johnson wrote that during the arrest, Warnisher accidentally hit him on the lip with his taser.

According to transcripts, Davis told internal affairs Smylie "didn't seem like a threat." Davis added that Warnisher seemed "a little impatient with the de-escalation I was trying to use."

A fourth officer, Michael Vogel, tried to console Smylie's crying cousin, and then joined the three other police who had Smylie on the ground. Vogel later told internal affairs that he did not see Smylie hit anyone or hear her say anything threatening.

According to police interview transcripts, Smylie said about Warnisher, "I don't want to say he smacked me. I don't think it was a smack but he pushed my face away from the direction of his." Warnisher told investigators, "She could've run into my fist. I never punched her."

While Smylie was in the back of Warnisher's patrol car waiting to be taken to jail, Warnisher went into her car. From the pocket in the side door he pulled out what looked like a black plastic bag. Then he took out a small pink stun gun – an electronic device, typically used for self defense. He placed it back in her vehicle. Later, Warnisher wrote in his police report that he had seen the stun gun before arresting Smylie but chose not to address it with her.

Davis went back to his own car, his body camera still filming. "Oh my gosh, Chance," he said to himself. "All this over a traffic stop."

Questionable force

Springfield Police Department policy states, "When feasible and safe to do so, officers shall attempt to de-escalate all incidents. Officers will not use more force in any situation than is reasonably necessary under the circumstances."

Deborah Anthony, a legal studies professor at University of Illinois Springfield who specializes in civil rights law, reviewed Warnisher's body camera footage of the traffic stop and Smylie's arrest.

She echoed that the use of force should be "proportional to what's necessary, especially for officer and bystander safety." In this case, "there were multiple officers, and a young woman who was not going to be able to flee or injure them," she said. "Using additional force, in the form of a taser, would seem excessive."

She said in matters concerning the Fourth Amendment, which is meant to protect citizens from unreasonable search and seizure, courts have determined that "even non-deadly force is unreasonable" in the case of minor infractions when a person is not attempting to flee or resist arrest.

Officers on the scene agreed that Smylie was resisting arrest, but that she was not a physical threat. "In practice, the courts have tended to have quite a bit of deference towards the judgments of officers when there's any claim of noncompliance," said Anthony.

Anthony said the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that officers have the right to require anyone they pull over to exit a vehicle. "And they don't have to have any reason beyond that they pulled you over for violating the traffic law," said Anthony. "It may seem contrary to common sense or fairness, and maybe for some people even contrary to their own safety," she said. "But that is the law."

The Supreme Court decision is a useful tool because it makes citizens "uncomfortable," Warnisher said, according to the interview transcript. "I get them out of the car, get them out of their safety zone, their element. It gives me a little bit of a tactful advantage," he told internal affairs.

According to body camera footage, Warnisher claimed Smylie hit him before tasing her during the arrest. But no officers who were on the scene and interviewed by the department said they saw that happen. Warnisher later told internal affairs "after reviewing the body camera I can't prove that she hit me. It could've been another officer, you know, with an elbow," according to the police interview transcript.

"The taser program is essentially one more tool in the tool bag to assist law enforcement officers when dealing with use-of-force instances. It is designed to offer an alternative, in certain situations, with the hope of reducing officer and suspect injuries," Springfield's Assistant Chief Ken Scarlette wrote to Illinois Times via email. "All use-of-force incidents are dynamic and typically there are multiple avenues to achieve the desired, peaceful outcome. The use of the taser is one of those avenues."

The question of the stun gun in Smylie's vehicle came up in the department's internal affairs investigation. If Warnisher did in fact notice it in the vehicle before arresting Smylie, why didn't he warn Davis about it when he asked him to approach the vehicle? "I forgot," Warnisher told internal affairs.

Smylie said the small pink stun gun belonged to a friend who left it in her car, and she had forgotten it was there. Anthony said when Warnisher used his taser on Smylie, she appeared far removed from the stun gun in her vehicle. By that time, she was on the ground and surrounded by multiple officers. "Whatever might have been in her car at that point I think was irrelevant in terms of justifying the force that they were using then," said Anthony.

Conflicting messages

Through the police union, Warnisher declined to provide comment for this story. Springfield Police Benevolent and Protective Association Unit 5 president Don Edwards wrote to Illinois Times via email that comment from officers is prohibited by department policy.

According to an internal affairs report dated Nov. 18, 2020, summarizing the police department's investigation and findings: "The complainant (Smylie) alleges that Warnisher's demeanor was aggressive from the start while interacting with her and unprofessional as Warnisher referred to her as a 'mouthy 20-year-old' several times. She felt the amount of force was unnecessary as she was no threat to Warnisher but only mouthy as Warnisher described."

In the report, the department concluded Smylie was uncooperative and that Warnisher was "extremely tolerant." Smylie "was forcefully taken out of the vehicle and drive-stunned with a taser by Warnisher to gain compliance. Smylie was actively resisting."

The report listed two alleged rule violations, regarding "use of force" and "courtesy and image" and exonerated Warnisher of both – meaning his actions were "justified, legal or proper, and that no misconduct was involved."

That seemed to counter a letter Smylie received from the department, dated Dec. 11, 2020, in which Chief Kenny Winslow wrote to her that Warnisher's conduct was "contrary with department policy. You may be assured that this department does not tolerate such actions. The appropriate disciplinary measures have been initiated."

This letter from Winslow to Smylie was not originally provided to Illinois Times via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. After Illinois Times questioned the department as to why Smylie was told Warnisher's conduct was contrary to department policy when the report provided by the department to Illinois Times through a FOIA request seemed to counter that, the department provided the letter. At the same time, the department provided another letter with the same date – Dec. 11, 2020 – addressed to Warnisher.

In the letter to Warnisher, Winslow referred to an additional allegation. It was about how Warnisher handled finding the pink stun gun in Smylie's car. In a written reprimand from Winslow, Warnisher was told he had failed to investigate the legality of Smylie's possession of the stun gun. This was a violation of department policy. Still, Warnisher's other conduct concerning Smylie was not in violation of policy, according to the records provided to Illinois Times.

The department missed a legal deadline for a FOIA request made by Illinois Times for Warnisher's training records and personnel file. When the department provided the records, there was a document dated the same day the records were provided – April 21, 2021. It was titled "training school info" and stated that as part of the "discipline/training imposed" in regards to the incident with Smylie, Warnisher took three separate day-long classes in October, November and December of last year. They were about use of force, modern policing and "how to build trust without compromising officer safety." Two webinars he took were also listed, about "police and minority relations" and de-escalation techniques.

The document states that Warnisher was removed from his position in the field and placed at Springfield Police Academy to complete the webinars and "other informal training." Personnel records show that Warnisher was reassigned to the field by at least Nov. 2, 2020.

"Is it right? No."

Public records also show that in four separate instances, the Springfield Police Department investigated additional citizen complaints against Warnisher since his 2004 hire. Records show the department ruled either to exonerate or to not sustain the allegations. That is, except for one allegation over an incident from February 2020. Warnisher had arrested a man over his attempted use of an allegedly forged $100 bill to pay for pizza.

A department investigator quoted Warnisher as having called the man, who on body camera footage appeared to be a person of color, a "fucking dumb son of a bitch," a "fucking moron" and a "dumb shit." The department found Warnisher had violated its courtesy and image rule.

In May 2020, less than half a year before Warnisher would arrest Smylie, Assistant Chief Scarlette wrote in a report, "By Officer Warnisher's own admission, he has been counseled by multiple supervisors as to his use of language and his interaction with the public. Clearly he has not heeded the advice."

Scarlette wrote that Warnisher should serve a one-day suspension, undergo communication training and seek at least one visit for anger management assistance. Scarlette told Illinois Times he could not comment on the personnel matter, but offered: "The department is committed to de-escalation training. In fact, we've included de-escalation in our use-of-force policy updates here recently."

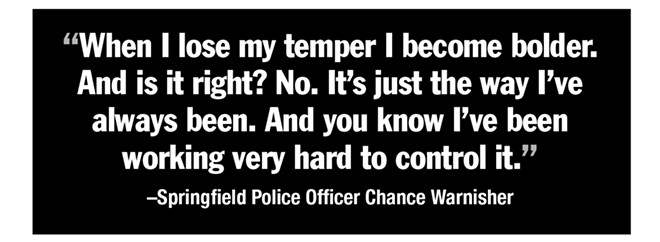

Warnisher told internal affairs he was sick that day in February when he spewed vulgarities at a suspect. "I don't have a lot of patience to begin with but I even have less patience when I'm irritated and sick," the internal affairs transcript read. Warnisher went on, "I was having a bad day. ... When I lose my temper I become bolder. And is it right? No. It's just the way I've always been. And you know I've been working very hard to control it."

Court and crib

Smylie said she knew she was pregnant that day in September, but she hadn't told family until after her arrest. It wasn't the way she wanted them to find out. She said she suffered minor injuries – a bruised knee, a jammed finger, hurt wrists from the handcuffs, marking from the taser. Those injuries have healed and she's planning for the arrival of her first child, a son. But the arrest has caused lingering stress, she told Illinois Times.

The encounter impacted her family as well. Her mother came along to the station to review the tape for the internal affairs investigation after Smylie's arrest. "It made her sick to her stomach," said Smylie. Her mother could not watch the video in full. She said her cousin won't ride in the car with her. It brings him bad memories. Smylie understands. She said she gets anxious around police now.

Smylie said for a while, she shouldered some of the blame for putting her unborn child in harm's way. But later she came to feel like Warnisher was responsible for how he chose to handle the situation. "I don't know if it was a bad morning for him. I don't know what it was. But it just seemed like this was gonna happen no matter what," she told Illinois Times.

"This is a heart issue and this officer was angry. He was mean," she said. "I don't believe that's what the Springfield Police Department stands for." She still wants accountability, only now it's more personal than when she organized a rally against police brutality nearly a year ago.

Smylie said she has struggled to find a lawyer to represent her. Retaining one is expensive. But she wants her record cleared of the "resisting arrest of a peace officer" misdemeanor charge she faces from that day. Her next court hearing is scheduled for May 5 – two days after her baby is due.

Smylie is 21 now. She's young, but she knows there's a difference between individual and systemic racism. She won't claim to know whether Warnisher racially profiled her. But she said the criminal justice system has a long history of systemic racism – of disproportionately arresting, imprisoning and brutalizing people of color.

"You can't lose your touch to humanity," she said about police. Smylie said she prays that her son will never have to witness a situation similar to the one she went through. "The only thing I can do is train my son to cooperate, to do the best he can at being a good citizen," she said. "We can't control anything else."

Contact Rachel Otwell at [email protected].